Other people's money, and how the bankers use it 1914

CHAPTER 3 - INTERLOCKING DIRECTORATES

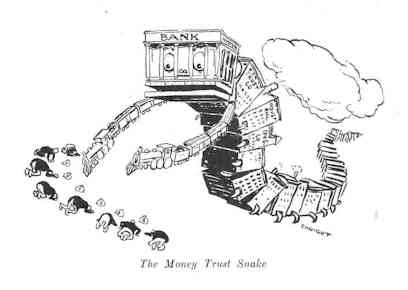

Illustration from Harper's Weekly December 13, 1913 by Walter J. Enright

- By Justice Louis Brandeis

The practice of interlocking directorates is the root of many evils. It offends laws human and divine. Applied to rival corporations, it tends to the suppression of competition and to violation of the Sherman law. Applied to corporations which deal with each other, it tends to disloyalty and to violation of the fundamental law that no man can serve two masters. In either event it tends to inefficiency; for it removes incentive and destroys soundness of judgment. It is undemocratic, for it rejects the platform: "A fair field and no favors,"—substituting the pull of privilege for the push of manhood. It is the most potent instrument of the Money Trust. Break the control so exercised by the investment bankers over railroads, public-service and industrial corporations, over banks, life insurance and trust companies, and a long step will have been taken toward attainment of the New Freedom.

The term "Interlocking directorates" is here used in a broad sense as including all intertwined conflicting interests, whatever the form, and by whatever device effected. The objection extends alike to contracts of a corporation whether with one of its directors individually, or with a firm of which he is a member, or with another corporation in which he is interested as an officer or director or stockholder. The objection extends likewise to men holding the inconsistent position of director in two potentially competing corporations, even if those corporations do not actually deal with each other.

THE ENDLESS CHAIN

A single example will illustrate the vicious circle of control—the endless chain—through which our financial oligarchy now operates:

J. P. Morgan (or a partner), a director of the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad, causes that company to sell to J. P. Morgan & Co. an issue of bonds. J. P. Morgan & Co. borrow the money with which to pay for the bonds from the Guaranty Trust Company, of which Mr. Morgan (or a partner) is a director. J. P. Morgan & Co. sell the bonds to the Penn Mutual Life Insurance Company, of which Mr. Morgan (or a partner) is a director. The New Haven spends the proceeds of the bonds in purchasing steel rails from the United States Steel Corporation, of which Mr. Morgan (or a partner) is a director. The United States Steel Corporation spends the proceeds of the rails in purchasing electrical supplies from the General Electric Company, of which Mr. Morgan (or a partner) is a director. The General Electric sells supplies to the Western Union Telegraph Company, a subsidiary of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company; and in both Mr. Morgan (or a partner) is a director. The Telegraph Company has an exclusive wire contract with the Reading, of which Mr. Morgan (or a partner) is a director. The Reading buys its passenger cars from the Pullman Company, of which Mr. Morgan (or a partner) is a director. The Pullman Company buys (for local use) locomotives from the Baldwin Locomotive Company, of which Mr. Morgan (or a partner) is a director. The Reading, the General Electric, the Steel Corporation and the New Haven, like the Pullman, buy locomotives from the Baldwin Company. The Steel Corporation, the Telephone Company, the New Haven, the Reading, the Pullman and the Baldwin Companies, like the Western Union, buy electrical supplies from the General Electric. The Baldwin, the Pullman, the Reading, the Telephone, the Telegraph and the General Electric companies, like the New Haven, buy steel products from the Steel Corporation. Each and every one of the companies last named markets its securities through J. P. Morgan & Co.; each deposits its funds with J. P. Morgan & Co.; and with these funds of each, the firm enters upon further operations.

This specific illustration is in part suppositious; but it represents truthfully the operation of interlocking directorates. Only it must be multiplied many times and with many permutations to represent fully the extent to which the interests of a few men are intertwined. Instead of taking the New Haven as the railroad starting point in our example, the New York Central, the Santa Fe, the Southern, the Lehigh Valley, the Chicago and Great Western, the Erie or the Père Marquette might have been selected; instead of the Guaranty Trust Company as the banking reservoir, any one of a dozen other important banks or trust companies; instead of the Penn Mutual as purchaser of the bonds, other insurance companies; instead of the General Electric, its qualified competitor, the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company. The chain is indeed endless; for each controlled corporation is entwined with many others.

As the nexus of "Big Business" the Steel Corporation stands, of course, preeminent: The Stanley Committee showed that the few men who control the Steel Corporation, itself an owner of important railroads, are directors also in twenty-nine other railroad systems, with 126,000 miles of line (more than half the railroad mileage of the United States), and in important steamship companies. Through all these alliances and the huge traffic it controls, the Steel Corporation's influence pervades railroad and steamship companies—not as carriers only—but as the largest customers for steel. And its influence with users of steel extends much further. These same few men are also directors in twelve steel-using street railway systems, including some of the largest in the world. They are directors in forty machinery and similar steel-using manufacturing companies; in many gas, oil and water companies, extensive users of iron products; and in the great wire-using telephone and telegraph companies. The aggregate assets of these different corporations—through which these few men exert their influence over the business of the United States—exceeds sixteen billion dollars.

Obviously, interlocking directorates, and all that term implies, must be effectually prohibited before the freedom of American business can be regained. The prohibition will not be an innovation. It will merely give full legal sanction to the fundamental law of morals and of human nature: that "No man can serve two masters." The surprising fact is that a principle of equity so firmly rooted should have been departed from at all in dealing with corporations. For no rule of law has, in other connections, been more rigorously applied, than that which prohibits a trustee from occupying inconsistent positions, from dealing with himself, or from using his fiduciary position for personal profit. And a director of a corporation is as obviously a trustee as persons holding similar positions in an unincorporated association, or in a private trust estate, who are called specifically by that name. The Courts have recognized this fully.

Thus, the Court of Appeals of New York declared in an important case:

"While not technically trustees, for the title of the corporate property was in the corporation itself, they were charged with the duties and subject to the liabilities of trustees. Clothed with the power of controlling the property and managing the affairs of the corporation without let or hindrance, as to third persons, they were its agents; but as to the corporation itself equity holds them liable as trustees. While courts of law generally treat the directors as agents, courts of equity treat them as trustees, and hold them to a strict account for any breach of the trust relation. For all practical purposes they are trustees, when called upon in equity to account for their official conduct."

NULLIFYING THE LAW

But this wholesome rule of business, so clearly laid down, was practically nullified by courts in creating two unfortunate limitations, as concessions doubtless to the supposed needs of commerce.

First: Courts held valid contracts between a corporation and a director, or between two corporations with a common director, where it was shown that in making the contract, the corporation was represented by independent directors and that the vote of the interested director was unnecessary to carry the motion and his presence was not needed to constitute a quorum.

Second: Courts held that even where a common director participated actively in the making of a contract between two corporations, the contract was not absolutely void, but voidable only at the election of the corporation.

The first limitation ignored the rule of law that a beneficiary is entitled to disinterested advice from all his trustees, and not merely from some; and that a trustee may violate his trust by inaction as well as by action. It ignored, also, the laws of human nature, in assuming that the influence of a director is confined to the act of voting. Every one knows that the most effective work is done before any vote is taken, subtly, and without provable participation. Every one should know that the denial of minority representation on boards of directors has resulted in the domination of most corporations by one or two men; and in practically banishing all criticism of the dominant power. And even where the board is not so dominated, there is too often that "harmonious cooperation" among directors which secures for each, in his own line, a due share of the corporation's favors.

The second limitation—by which contracts, in the making of which the interested director participates actively, are held merely voidable instead of absolutely void—ignores the teachings of experience. To hold such contracts merely voidable has resulted practically in declaring them valid. It is the directors who control corporate action; and there is little reason to expect that any contract, entered into by a board with a fellow director, however unfair, would be subsequently avoided. Appeals from Philip drunk to Philip sober are not of frequent occurrence, nor very fruitful. But here we lack even an appealing party. Directors and the dominant stockholders would, of course, not appeal; and the minority stockholders have rarely the knowledge of facts which is essential to an effective appeal, whether it be made to the directors, to the whole body of stockholders, or to the courts. Besides, the financial burden and the risks incident to any attempt of individual stockholders to interfere with an existing management is ordinarily prohibitive. Proceedings to avoid contracts with directors are, therefore, seldom brought, except after a radical change in the membership of the board. And radical changes in a board's membership are rare. Indeed the Pujo Committee reports:

"None of the witnesses, (the leading American bankers testified) was able to name an instance in the history of the country in which the stockholders had succeeded in overthrowing an existing management in any large corporation. Nor does it appear that stockholders have ever even succeeded in so far as to secure the investigation of an existing management of a corporation to ascertain whether it has been well or honestly managed."

Mr. Max Pam proposed in the April, 1913, Harvard Law Review, that the government come to the aid of minority stockholders. He urged that the president of every corporation be required to report annually to the stockholders, and to state and federal officials every contract made by the company in which any director is interested; that the Attorney-General of the United States or the State investigate the same and take proper proceedings to set all such contracts aside and recover any damages suffered; or without disaffirming the contracts to recover from the interested directors the profits derived therefrom. And to this end also, that State and National Bank Examiners, State Superintendents of Insurance, and the Interstate Commerce Commission be directed to examine the records of every bank, trust company, insurance company, railroad company and every other corporation engaged in interstate commerce. Mr. Pam's views concerning interlocking directorates are entitled to careful study. As counsel prominently identified with the organization of trusts, he had for years full opportunity of weighing the advantages and disadvantages of "Big Business." His conviction that the practice of interlocking directorates is a menace to the public and demands drastic legislation, is significant. And much can be said in support of the specific measure which he proposes. But to be effective, the remedy must be fundamental and comprehensive.

THE ESSENTIALS OF PROTECTION

Protection to minority stockholders demands that corporations be prohibited absolutely from making contracts in which a director has a private interest, and that all such contracts be declared not voidable merely, but absolutely void.

In the case of railroads and public-service corporations (in contradistinction to private industrial companies), such prohibition is demanded, also, in the interests of the general public. For interlocking interests breed inefficiency and disloyalty; and the public pays, in higher rates or in poor service, a large part of the penalty for graft and inefficiency. Indeed, whether rates are adequate or excessive cannot be determined until it is known whether the gross earnings of the corporation are properly expended. For when a company's important contracts are made through directors who are interested on both sides, the common presumption that money spent has been properly spent does not prevail. And this is particularly true in railroading, where the company so often lacks effective competition in its own field.

But the compelling reason for prohibiting interlocking directorates is neither the protection of stockholders, nor the protection of the public from the incidents of inefficiency and graft. Conclusive evidence (if obtainable) that the practice of interlocking directorates benefited all stockholders and was the most efficient form of organization, would not remove the objections. For even more important than efficiency are industrial and political liberty; and these are imperiled by the Money Trust. Interlocking directorates must be prohibited, because it is impossible to break the Money Trust without putting an end to the practice in the larger corporations.

BANKS AS PUBLIC-SERVICE CORPORATIONS

The practice of interlocking directorates is peculiarly objectionable when applied to banks, because of the nature and functions of those institutions. Bank deposits are an important part of our currency system. They are almost as essential a factor in commerce as our railways. Receiving deposits and making loans therefrom should be treated by the law not as a private business, but as one of the public services. And recognizing it to be such, the law already regulates it in many ways. The function of a bank is to receive and to loan money. It has no more right than a common carrier to use its powers specifically to build up or to destroy other businesses. The granting or withholding of a loan should be determined, so far as concerns the borrower, solely by the interest rate and the risk involved; and not by favoritism or other considerations foreign to the banking function. Men may safely be allowed to grant or to deny loans of their own money to whomsoever they see fit, whatsoever their motive may be. But bank resources are, in the main, not owned by the stockholders nor by the directors. Nearly three-fourths of the aggregate resources of the thirty-four banking institutions in which the Morgan associates hold a predominant influence are represented by deposits. The dependence of commerce and industry upon bank deposits, as the common reservoir of quick capital is so complete, that deposit banking should be recognized as one of the businesses "affected with a public interest." And the general rule which forbids public-service corporations from making unjust discriminations or giving undue preference should be applied to the operations of such banks.

Senator Owen, Chairman of the Committee on Banking and Currency, said recently:

"My own judgment is that a bank is a public-utility institution and cannot be treated as a private affair, for the simple reason that the public is invited, under the safeguards of the government, to deposit its money with the bank, and the public has a right to have its interests safeguarded through organized authorities. The logic of this is beyond escape. All banks in the United States, public and private, should be treated as public-utility institutions, where they receive public deposits."

The directors and officers of banking institutions must, of course, be entrusted with wide discretion in the granting or denying of loans. But that discretion should be exercised, not only honestly as it affects stockholders, but also impartially as it affects the public. Mere honesty to the stockholders demands that the interests to be considered by the directors be the interests of all the stockholders; not the profit of the part of them who happen to be its directors. But the general welfare demands of the director, as trustee for the public, performance of a stricter duty. The fact that the granting of loans involves a delicate exercise of discretion makes it difficult to determine whether the rule of equality of treatment, which every public-service corporation owes, has been performed. But that difficulty merely emphasizes the importance of making absolute the rule that banks of deposit shall not make any loan nor engage in any transaction in which a director has a private interest. And we should bear this in mind: If privately-owned banks fail in the public duty to afford borrowers equality of opportunity, there will arise a demand for government-owned banks, which will become irresistible.

The statement of Mr. Justice Holmes of the Supreme Court of the United States, in the Oklahoma Bank case, is significant:

"We cannot say that the public interests to which we have adverted, and others, are not sufficient to warrant the State in taking the whole business of banking under its control. On the contrary we are of opinion that it may go on from regulation to prohibition except upon such conditions as it may prescribe."

OFFICIAL PRECEDENTS

Nor would the requirement that banks shall make no loan in which a director has a private interest impose undue hardships or restrictions upon bank directors. It might make a bank director dispose of some of his investments and refrain from making others; but it often happens that the holding of one office precludes a man from holding another, or compels him to dispose of certain financial interests.

A judge is disqualified from sitting in any case in which he has even the smallest financial interest; and most judges, in order to be free to act in any matters arising in their court, proceed, upon taking office, to dispose of all investments which could conceivably bias their judgment in any matter that might come before them. An Interstate Commerce Commissioner is prohibited from owning any bonds or stocks in any corporation subject to the jurisdiction of the Commission. It is a serious criminal offence for any executive officer of the federal government to transact government business with any corporation in the pecuniary profits of which he is directly or indirectly interested.

And the directors of our great banking institutions, as the ultimate judges of bank credit, exercise today a function no less important to the country's welfare than that of the judges of our courts, the interstate commerce commissioners, and departmental heads.

SCOPE OF THE PROHIBITION

In the proposals for legislation on this subject, four important questions are presented:

1. Shall the principle of prohibiting interlocking directorates in potentially competing corporations be applied to state banking institutions, as well as the national banks?

2. Shall it be applied to all kinds of corporations or only to banking institutions?

3. Shall the principle of prohibiting corporations from entering into transactions in which the management has a private interest be applied to both directors and officers or be confined in its application to officers only?

4. Shall the principle be applied so as to prohibit transactions with another corporation in which one of its directors is interested merely as a stockholder?

Go to the next chapter

Return to the table of contents