Other people's money, and how the bankers use it, 1914

CHAPTER 10 - THE INEFFICIENCY OF THE OLIGARCHS

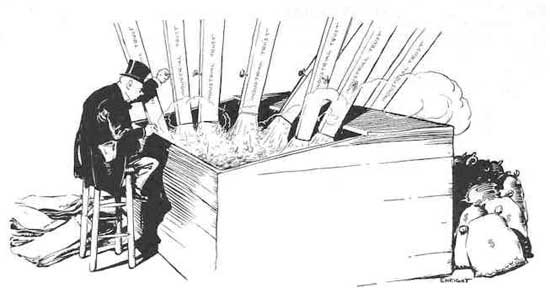

Illustration from Harper's Weekly January 3, 1914 by Walter J. Enright

- By Justice Louis Brandeis -

We must break the Money Trust or the Money Trust will break us. The Interstate Commerce Commission said in its report on the most disastrous of the recent wrecks on the New Haven Railroad: "On this directorate were and are men whom the confiding public recognize as magicians in the art of finance, and wizards in the construction, operation, and consolidation of great systems of railroads. The public therefore rested secure that with the knowledge of the railroad art possessed by such men investments and travel should both be safe. Experience has shown that this reliance of the public was not justified as to either finance or safety." This failure of banker-management is not surprising. The surprise is that men should have supposed it would succeed. For banker-management contravenes the fundamental laws of human limitations: First, that no man can serve two masters; second, that a man cannot at the same time do many things well.

SEEMING SUCCESSES

There are numerous seeming exceptions to these rules; and a relatively few real ones. Of course, many banker-managed properties have been prosperous; some for a long time, at the expense of the public; some for a shorter time, because of the impetus attained before they were banker-managed. It is not difficult to have a large net income, where one has the field to oneself, has all the advantage privilege can give, and may "charge all the traffic will bear." And even in competitive business the success of a long-established, well-organized business with a widely extended good-will, must continue for a considerable time; especially if buttressed by intertwined relations constantly giving it the preference over competitors. The real test of efficiency comes when success has to be struggled for; when natural or legal conditions limit the charges which may be made for the goods sold or service rendered. Our banker-managed railroads have recently been subjected to such a test, and they have failed to pass it. "It is only,"' says Goethe, "when working within limitations, that the master is disclosed."

WHY OLIGARCHY FAILS

Banker-management fails, partly because the private interest destroys soundness of judgment and undermines loyalty. It fails partly, also, because banker directors are led by their occupation (and often even by the mere fact of their location remote from the operated properties) to apply a false test in making their decisions. Prominent in the banker-director mind is always this thought: "What will be the probable effect of our action upon the market value of the company's stock and bonds, or, indeed, generally upon stock exchange values?" The stock market is so much a part of the investment-banker's life, that he cannot help being affected by this consideration, however disinterested he may be. The stock market is sensitive. Facts are often misinterpreted "by the street'" or by investors. And with the best of intentions, directors susceptible to such influences are led to unwise decisions in the effort to prevent misinterpretations. Thus, expenditures necessary for maintenance, or for the ultimate good of a property are often deferred by banker-directors, because of the belief that the making of them now, would (by showing smaller net earnings), create a bad, and even false, impression on the market. Dividends are paid which should not be, because of the effect which it is believed reduction or suspension would have upon the market value of the company's securities. To exercise a sound judgment in the difficult affairs of business is, at best, a delicate operation. And no man can successfully perform that function whose mind is diverted, however innocently, from the study of, "what is best in the long run for the company of which I am director?" The banker-director is peculiarly liable to such distortion of judgment by reason of his occupation and his environment. But there is a further reason why, ordinarily, banker-management must fail.

THE ELEMENT OF TIME

The banker, with his multiplicity of interests, cannot ordinarily give the time essential to proper supervision and to acquiring that knowledge of the facts necessary to the exercise of sound judgment. The Century Dictionary tells us that a Director is "one who directs; one who guides, superintends, governs and manages." Real efficiency in any business in which conditions are ever changing must ultimately depend, in large measure, upon the correctness of the judgment exercised, almost from day to day, on the important problems as they arise. And how can the leading bankers, necessarily engrossed in the problems of their own vast private business, get time to know and to correlate the facts concerning so many other complex businesses? Besides, they start usually with ignorance of the particular business which they are supposed to direct. When the last paper was signed which created the Steel Trust, one of the lawyers (as Mr. Perkins frankly tells us) said: "That signature is the last one necessary to put the Steel industry, on a large scale, into the hands of men who do not know anything about it."

AVOCATIONS OF THE OLIGARCHS

The New Haven System is not a railroad, but an agglomeration of a railroad plus 121 separate corporations, control of which was acquired by the New Haven after that railroad attained its full growth of about 2,000 miles of line. In administering the railroad and each of the properties formerly managed through these 122 separate companies, there must arise from time to time difficult questions on which the directors should pass judgment. The real managing directors of the New Haven system during the decade of its decline were: J. Pierpont Morgan, George F. Baker, and William Rockefeller. Mr. Morgan was, until his death in 1913, the head of perhaps the largest banking house in the world. Mr. Baker was, until 1909, President and then Chairman of the Board of Directors of one of America's leading banks (the First National of New York), and Mr. Rockefeller was, until 1911, President of the Standard Oil Company. Each was well advanced in years. Yet each of these men, besides the duties of his own vast business, and important private interests, undertook to "guide, superintend, govern and manage," not only the New Haven but also the following other corporations, some of which were similarly complex: Mr. Morgan, 48 corporations, including 40 railroad corporations, with at least 100 subsidiary companies, and 16,000 miles of line; 3 banks and trust or insurance companies; 5 industrial and public service companies. Mr. Baker, 48 corporations, including 15 railroad corporations, with at least 158 subsidiaries; and 37,400 miles of track; 18 banks, and trust or insurance companies; 15 public-service corporations and industrial concerns. Mr. Rockefeller, 37 corporations, including 23 railroad corporations with at least 117 subsidiary companies, and 26,400 miles of line; 5 banks, trust or insurance companies; 9 public service companies and industrial concerns.

SUBSTITUTES

It has been urged that in view of the heavy burdens which the leaders of finance assume in directing Business-America, we should be patient of error and refrain from criticism, lest the leaders be deterred from continuing to perform this public service. A very respectable Boston daily said a few days after Commissioner McCord's report on the North Haven wreck: "It is believed that the New Haven pillory repeated with some frequency will make the part of railroad director quite undesirable and hard to fill, and more and more avoided by responsible men. Indeed it may even become so that men will have to be paid a substantial salary to compensate them in some degree for the risk involved in being on the board of directors." But there is no occasion for alarm. The American people have as little need of oligarchy in business as in politics. There are thousands of men in America who could have performed for the New Haven stockholders the task of one "who guides, superintends, governs and manages," better than did Mr. Morgan, Mr. Baker and Mr. Rockefeller. For though possessing less native ability, even the average business man would have done better than they, because working under proper conditions. There is great strength in serving with singleness of purpose one master only. There is great strength in having time to give to a business the attention which its difficult problems demand. And tens of thousands more Americans could be rendered competent to guide our important businesses. Liberty is the greatest developer. Herodotus tells us that while the tyrants ruled, the Athenians were no better fighters than their neighbors; but when freed, they immediately surpassed all others. If industrial democracy—true coöperation—should be substituted for industrial absolutism, there would be no lack of industrial leaders.

ENGLAND'S BIG BUSINESS

England, too, has big business. But her big business is the Coöperative Wholesale Society, with a wonderful story of 50 years of beneficent growth. Its annual turnover is now about $150,000,000—an amount exceeded by the sales of only a few American industrials; an amount larger than the gross receipts of any American railroad, except the Pennsylvania and the New York Central systems. Its business is very diversified, for its purpose is to supply the needs of its members. It includes that of wholesale dealer, of manufacturer, of grower, of miner, of banker, of insurer and of carrier. It operates the biggest flour mills and the biggest shoe factory in all Great Britain. It manufactures woolen cloths, all kinds of men's, women's and children's clothing, a dozen kinds of prepared foods, and as many household articles. It operates creameries. It carries on every branch of the printing business. It is now buying coal lands. It has a bacon factory in Denmark, and a tallow and oil factory in Australia. It grows tea in Ceylon. And through all the purchasing done by the Society runs this general principle: Go direct to the source of production, whether at home or abroad, so as to save commissions of middlemen and agents. Accordingly, it has buyers and warehouses in the United States, Canada, Australia, Spain, Denmark and Sweden. It owns steamers plying between Continental and English ports. It has an important banking department; it insures the property and person of its members. Every one of these departments is conducted in competition with the most efficient concerns in their respective lines in Great Britain. The Coöperative Wholesale Society makes its purchases, and manufactures its products, in order to supply the 1399 local distributive, coöperative societies scattered over all England; but each local society is at liberty to buy from the wholesale society, or not, as it chooses; and they buy only if the Coöperative Wholesale sells at market prices. This the Coöperative actually does; and it is able besides to return to the local a fair dividend on its purchases.

INDUSTRIAL DEMOCRACY

Now, how are the directors of this great business chosen? Not by England's leading bankers, or other notabilities, supposed to possess unusual wisdom; but democratically, by all of the people interested in the operations of the Society. And the number of such persons who have directly or indirectly a voice in the selection of the directors of the English Coöperative Wholesale Society is 2,750,000. For the directors of the Wholesale Society are elected by vote of the delegates of the 1399 retail societies. And the delegates of the retail societies are, in turn, selected by the members of the local societies;—that is, by the consumers, on the principle of one man, one vote, regardless of the amount of capital contributed. Note what kind of men these industrial democrats select to exercise executive control of their vast organization. Not all-wise bankers or their dummies, but men who have risen from the ranks of coöperation; men who, by conspicuous service in the local societies have won the respect and confidence of their fellows. The directors are elected for one year only; but a director is rarely un-seated. J. T. W. Mitchell was president of the Society continuously for 21 years. Thirty-two directors are selected in this manner. Each gives to the business of the Society his whole time and attention; and the aggregate salaries of the thirty-two is less than that of many a single executive in American corporations; for these directors of England's big business serve each for a salary of about $1500 a year. The Coöperative Wholesale Society of England is the oldest and largest of these institutions. But similar wholesale societies exist in 15 other countries. The Scotch Society (which William Maxwell has served most efficiently as President for thirty years at a salary never exceeding $38 a week) has a turn-over of more than $50,000,000 a year.

A REMEDY FOR TRUSTS

Albert Sonnichsen, General Secretary of the Cooperative League, tells in the American Review of Reviews for April, 1913, how the Swedish Wholesale Society curbed the Sugar Trust; how it crushed the Margerine Combine (compelling it to dissolve after having lost 2,300,000 crowns in the struggle); and how in Switzerland the Wholesale Society forced the dissolution of the Shoe Manufacturers Association. He tells also this memorable incident: "Six years ago, at an international congress in Cremona, Dr. Hans Müller, a Swiss delegate, presented a resolution by which an international wholesale society should be created. Luigi Luzzatti, Italian Minister of State and an ardent member of the movement, was in the chair. Those who were present say Luzzatti paused, his eyes lighted up, then, dramatically raising his hand, he said: ‘Dr. Muller proposes to the assembly a great idea—that of opposing to the great trusts, the Rockefellers of the world, a world-wide cooperative alliance which shall become so powerful as to crush the trusts.’ "

COOPERATION IN AMERICA

America has no Wholesale Cooperative Society able to grapple with the trusts. But it has some very strong retail societies, like the Tamarack of Michigan, which has distributed in dividends to its members $1,144,000 in 23 years. The recent high cost of living has greatly stimulated interest in the cooperative movement; and John Graham Brooks reports that we have already about 350 local distributive societies. The movement toward federation is progressing. There are over 100 cooperative stores in Minnesota, Wisconsin and other Northwestern states, many of which were organized by or through the zealous work of Mr. Tousley and his associates of the Right Relationship League and are in some ways affiliated. In New York City 83 organizations are affiliated with the Cooperative League. In New Jersey the societies have federated into the American Cooperative Alliance of Northern New Jersey. In California, long the seat of effective cooperative work, a central management committee is developing. And progressive Wisconsin has recently legislated wisely to develop cooperation throughout the state. Among our farmers the interest in cooperation is especially keen. The federal government has just established a separate bureau of the Department of Agriculture to aid in the study, development and introduction of the best methods of cooperation in the working of farms, in buying, and in distribution; and special attention is now being given to farm credits—a field of cooperation in which Continental Europe has achieved complete success, and to which David Lubin, America's delegate to the International Institute of Agriculture at Rome, has, among others, done much to direct our attention.

PEOPLE'S SAVINGS BANKS

The German farmer has achieved democratic banking. The 13,000 little cooperative credit associations, with an average membership of about 90 persons, are truly banks of the people, by the people and for the people. First: The banks' resources are of the people. These aggregate about $500,000,000. Of this amount $375,000,000 represents the farmers' savings deposits; $50,000,000, the farmers' current deposits; $6,000,000, the farmers' share capital; and $13,000,000, amounts earned and placed in the reserve. Thus, nearly nine-tenths of these large resources belong to the farmers—that is, to the members of the banks. Second: The banks are managed by the people—that is, the members. And membership is easily attained; for the average amount of paid-up share capital was, in 1909, less than $5 per member. Each member has one vote regardless of the number of his shares or the amount of his deposits. These members elect the officers. The committees and trustees (and often even, the treasurer) serve without pay: so that the expenses of the banks are, on the average, about $150 a year. Third: The banks are for the people. The farmers' money is loaned by the farmer to the farmer at a low rate of interest (usually 4 per cent. to 6 per cent.); the shareholders receiving, on their shares, the same rate of interest that the borrowers pay on their loans. Thus the resources of all farmers are made available to each farmer, for productive purposes. This democratic rural banking is not confined to Germany. As Henry W. Wolff says in his book on cooperative banks: "Propagating themselves by their own merits, little people's cooperative banks have overspread Germany, Italy, Austria, Hungary, Switzerland, Belgium. Russia is following up those countries; France is striving strenuously for the possession of cooperative credit. Servia, Roumania, and Bulgaria have made such credit their own. Canada has scored its first success on the road to its acquisition. Cyprus, and even Jamaica, have made their first start. Ireland has substantial first-fruits to show of her economic sowings. "South Africa is groping its way to the same goal. Egypt has discovered the necessity of cooperative banks, even by the side of Lord Cromer's pet creation, the richly endowed `agricultural bank.' India has made a beginning full of promise. And even in far Japan, and in China, people are trying to acclimatize the more perfected organizations of Schulze-Delitzsch and Raffeisen. The entire world seems girdled with a ring of cooperative credit. Only the United States and Great Britain still lag lamentably behind."

BANKERS' SAVINGS BANKS

The savings banks of America present a striking contrast to these democratic banks. Our savings banks also have performed a great service. They have provided for the people's funds safe depositories with some income return. Thereby they have encouraged thrift and have created, among other things, reserves for the proverbial "rainy day." They have also discouraged "old stocking" hoarding, which diverts the money of the country from the channels of trade. American savings banks are also, in a sense, banks of the people; for it is the people's money which is administered by them. The $4,500,000,000 deposits in 2,000 American savings banks belong to about ten million people, who have an average deposit of about $450. But our savings banks are not banks by the people, nor, in the full sense, for the people. First: American savings banks are not managed by the people. The stock-savings banks, most prevalent in the Middle West and the South, are purely commercial enterprises, managed, of course, by the stockholders’ representatives. The mutual savings banks, most prevalent in the Eastern states, have no stockholders; but the depositors have no voice in the management. The banks are managed by trustees for the people, practically a self-constituted and self-perpetuating body, composed of "leading" and, to a large extent, public-spirited citizens. Among them (at least in the larger cities) there is apt to be a predominance of investment bankers, and bank directors. Thus the three largest savings banks of Boston (whose aggregate deposits exceed those of the other 18 banks) have together 81 trustees. Of these, 52 are investment bankers or directors in other Massachusetts banks or trust companies. Second: The funds of our savings banks (whether stock or purely mutual) are not used mainly for the people. The depositors are allowed interest (usually from 3 to 4 per cent.). In the mutual savings banks they receive ultimately all the net earnings. But the money gathered in these reservoirs is not used to aid productively persons of the classes who make the deposits.

The depositors are largely wage earners, salaried people, or members of small tradesmen's families. Statically the money is used for them. Dynamically it is used for the capitalist. For rare, indeed, are the instances when savings banks' moneys are loaned to advance productively one of the depositor class. Such persons would seldom be able to provide the required security; and it is doubtful whether their small needs would, in any event, receive consideration. In 1912 the largest of Boston's mutual savings banks—the Provident Institution for Savings, which is the pioneer mutual savings bank of America—managed $53,000,000 of people’s money. Nearly one-half of the resources ($24,262,072) was invested in bonds—state, municipal, railroad, railway and telephone and in bank stock; or was deposited in national banks or trust companies. Two-fifths of the resources ($20,764,770) were loaned on real estate mortgages; and the average amount of a loan was $52,569. One-seventh of the resources ($7,566,612) was loaned on personal security; and the average of each of these loans was $54,830. Obviously, the "small man" is not conspicuous among the borrowers; and these large-scale investments do not even serve the individual depositor especially well; for this bank pays its depositors a rate of interest lower than the average. Even our admirable Postal Savings Bank system serves productively mainly the capitalist. These postal saving stations are in effect catch-basins merely, which collect the people's money for distribution among the national banks.

PROGRESS

Alphonse Desjardins of Levis, Province of Quebec, has demonstrated that cooperative credit associations are applicable, also, to at least some urban communities. Levis, situated on the St. Lawrence opposite the City of Quebec, is a city of 8,000 inhabitants. Desjardins himself is a man of the people. Many years ago he became impressed with the fact that the people's savings were not utilized primarily to aid the people productively. There were then located in Levis branches of three ordinary banks of deposit—a mutual savings bank, the postal savings bank, and three incorporated "loaners"; but the people were not served. After much thinking, he chanced to read of the European rural banks. He proceeded to work out the idea for use in Levis; and in 1900 established there the first "credit-union." For seven years he watched carefully the operations of this little bank. The pioneer union had accumulated in that period $80,000 in resources. It had made 2,900 loans to its members, aggregating $350,000; the loans averaging $120 in amount, and the interest rate 6 1/2 per cent. In all this time the bank had not met with a single loss. Then Desjardins concluded that democratic banking was applicable to Canada; and he proceeded to establish other credit-unions. In the last 5 years the number of credit-unions in the Province of Quebec has grown to 121; and 19 have been established in the Province of Ontario. Desjardins was not merely the pioneer. All the later credit-unions also have been established through his aid; and 24 applications are now in hand requesting like assistance from him. Year after year that aid has been given without pay by this public-spirited man of large family and small means, who lives as simply as the ordinary mechanic. And it is noteworthy that this rapidly extending system of cooperative credit-banks has been established in Canada wholely without government aid, Desjardins having given his services free, and his travelling expenses having been paid by those seeking his assistance.

In 1909, Massachusetts, under Desjardins' guidance, enacted a law for the incorporation of credit-unions. The first union established in Springfield, in 1910, was named after Herbert Myrick—a strong advocate of cooperative finance. Since then 25 other unions have been formed; and the names of the unions and of their officers disclose that 11 are Jewish, 8 French-Canadian, and 2 Italian—a strong indication that the immigrant is not unprepared for financial democracy. There is reason to believe that these people's banks will spread rapidly in the United States and that they will succeed. For the cooperative building and loan associations, managed by wage-earners and salary-earners, who joined together for systematic saving and ownership of houses—have prospered in many states. In Massachusetts, where they have existed for 35 years, their success has been notable—the number, in 1912, being 162, and their aggregate assets nearly $75,000,000.

Thus farmers, workingmen, and clerks are learning to use their little capital and their savings to help one another instead of turning over their money to the great bankers for safe keeping, and to be themselves exploited. And may we not expect that when the cooperative movement develops in America, merchants and manufacturers will learn from farmers and workingmen how to help themselves by helping one another, and thus join in attaining the New Freedom for all? When merchants and manufacturers learn this lesson, money kings will lose subjects, and swollen fortunes may shrink; but industries will flourish, because the faculties of men will be liberated and developed.

President Wilson has said wisely:

"No country can afford to have its prosperity originated by a small controlling class. The treasury of America does not lie in the brains of the small body of men now in control of the great enterprises… It depends upon the inventions of unknown men, upon the originations of unknown men, upon the ambitions of unknown men. Every country is renewed out of the ranks of the unknown, not out of the ranks of the already famous and powerful in control."

Return to the table of contents