3 NSA veterans speak out on whistle-blower: We told you so

- By Peter Eisler and Susan Page - USA TODAY - June 16, 2013

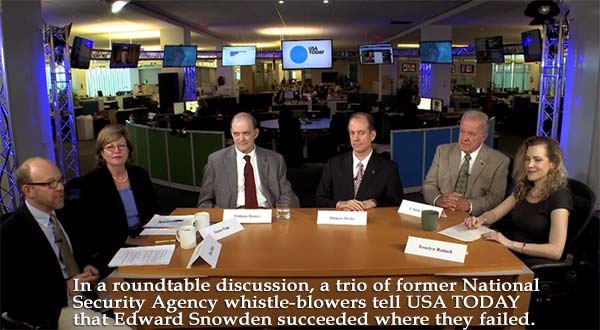

Three former officials at the National Security Agency have become outspoken critics of the agency and its spying methods. Their lawyer, Jesselyn Radack, has criticized practices she saw while working at the Justice Department.

In a roundtable discussion, a trio of former National Security Agency whistle-blowers tell USA TODAY that Edward Snowden succeeded where they failed.

When a National Security Agency contractor revealed top-secret details this month on the government's collection of Americans' phone and Internet records, one select group of intelligence veterans breathed a sigh of relief.

Thomas Drake, William Binney and J. Kirk Wiebe belong to a select fraternity: the NSA officials who paved the way.

For years, the three whistle-blowers had told anyone who would listen that the NSA collects huge swaths of communications data from U.S. citizens. They had spent decades in the top ranks of the agency, designing and managing the very data-collection systems they say have been turned against Americans. When they became convinced that fundamental constitutional rights were being violated, they complained first to their superiors, then to federal investigators, congressional oversight committees and, finally, to the news media.

To the intelligence community, the trio are villains who compromised what the government classifies as some of its most secret, crucial and successful initiatives. They have been investigated as criminals and forced to give up careers, reputations and friendships built over a lifetime.

Today, they feel vindicated.

They say the documents leaked by Edward Snowden, the 29-year-old former NSA contractor who worked as a systems administrator, proves their claims of sweeping government surveillance of millions of Americans not suspected of any wrongdoing. They say those revelations only hint at the programs' reach.

On Friday, USA TODAY brought Drake, Binney and Wiebe together for the first time since the story broke to discuss the NSA revelations. With their lawyer, Jesselyn Radack of the Government Accountability Project, they weighed their implications and their repercussions. They disputed the administration's claim of the impact of the disclosures on national security — and President Obama's argument that Congress and the courts are providing effective oversight.

And they have warnings for Snowden on what he should expect next.

Q: Did Edward Snowden do the right thing in going public?

William Binney: We tried to stay for the better part of seven years inside the government trying to get the government to recognize the unconstitutional, illegal activity that they were doing and openly admit that and devise certain ways that would be constitutionally and legally acceptable to achieve the ends they were really after. And that just failed totally because no one in Congress or — we couldn't get anybody in the courts, and certainly the Department of Justice and inspector general's office didn't pay any attention to it. And all of the efforts we made just produced no change whatsoever. All it did was continue to get worse and expand.

Q: So Snowden did the right thing?

Binney: Yes, I think he did.

Q: You three would not criticize him for going public from the start?

J. Kirk Wiebe: Correct.

Binney: In fact, I think he saw and read about what our experience was, and that was part of his decision-making.

Wiebe: We failed, yes.

Jesselyn Radack: Not only did they go through multiple and all the proper internal channels and they failed, but more than that, it was turned against them. ... The inspector general was the one who gave their names to the Justice Department for criminal prosecution under the Espionage Act. And they were all targets of a federal criminal investigation, and Tom ended up being prosecuted — and it was for blowing the whistle.

Q: There's a question being debated whether Snowden is a hero or a traitor.

Binney: Certainly he performed a really great public service to begin with by exposing these programs and making the government in a sense publicly accountable for what they're doing. At least now they are going to have some kind of open discussion like that.

But now he is starting to talk about things like the government hacking into China and all this kind of thing. He is going a little bit too far. I don't think he had access to that program. But somebody talked to him about it, and so he said, from what I have read, anyway, he said that somebody, a reliable source, told him that the U.S. government is hacking into all these countries. But that's not a public service, and now he is going a little beyond public service.

So he is transitioning from whistle-blower to a traitor.

Thomas Drake: He's an American who has been exposed to some incredible information regarding the deepest secrets of the United States government. And we are seeing the initial outlines and contours of a very systemic, very broad, a Leviathan surveillance state and much of it is in violation of the fundamental basis for our own country — in fact, the very reason we even had our own American Revolution. And the Fourth Amendment for all intents and purposes was revoked after 9/11. ...

He is by all definitions a classic whistle-blower and by all definitions he exposed information in the public interest. We're now finally having the debate that we've never had since 9/11.

Radack: "Hero or traitor?" was the original question. I don't like these labels, and they are putting people into categories of two extremes, villain or saint. ... By law, he fits the legal definition of a whistle-blower. He is someone who exposed broad waste, abuse and in his case illegality. ... And he also said he was making the disclosures for the public good and because he wanted to have a debate.

Q: James Clapper, the director of national intelligence, said Snowden's disclosures caused "huge, grave damage" to the United States. Do you agree?

Wiebe: No, I do not. I do not. You know, I've asked people: Do you generally believe there's government authorities collecting information about you on the Net or your phone? "Oh, of course." No one is surprised.

There's very little specificity in the slides that he made available (describing the PRISM surveillance program). There is far more specificity in the FISA court order that is bothersome.

Q: Did foreign governments, terrorist organizations, get information they didn't have already?

Binney: Ever since ... 1997-1998 ... those terrorists have known that we've been monitoring all of these communications all along. So they have already adjusted to the fact that we are doing that. So the fact that it is published in the U.S. news that we're doing that, has no effect on them whatsoever. They have already adjusted to that.

Radack: This comes up every time there's a leak. ... In Tom's case, Tom was accused of literally the blood of soldiers would be on his hands because he created damage. I think the exact words were, "When the NSA goes dark, soldiers die." And that had nothing to do with Tom's disclosure at all, but it was part of the fear mongering that generally goes with why we should keep these things secret.

Q: What did you learn from the document — the Verizon warrant issued by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court — that Snowden leaked?

Drake: It's an extraordinary order. I mean, it's the first time we've publicly seen an actual, secret, surveillance-court order. I don't really want to call it "foreign intelligence" (court) anymore, because I think it's just become a surveillance court, OK? And we are all foreigners now. By virtue of that order, every single phone record that Verizon has is turned over each and every day to NSA.

There is no probable cause. There is no indication of any kind of counterterrorism investigation or operation. It's simply: "Give us the data." ...

There's really two other factors here in the order that you could get at. One is that the FBI requesting the data. And two, the order directs Verizon to pass all that data to NSA, not the FBI.

Binney: What it is really saying is the NSA becomes a processing service for the FBI to use to interrogate information directly. ... The implications are that everybody's privacy is violated, and it can retroactively analyze the activity of anybody in the country back almost 12 years.

Now, the other point that is important about that is the serial number of the order: 13-dash-80. That means it's the 80th order of the court in 2013. ... Those orders are issued every quarter, and this is the second quarter, so you have to divide 80 by two and you get 40.

If you make the assumption that all those orders have to deal with companies and the turnover of material by those companies to the government, then there are at least 40 companies involved in that transfer of information. However, if Verizon, which is Order No. 80, and the first quarter got order No. 1 — then there can be as many as 79 companies involved.

So somewhere between 40 and 79 is the number of companies, Internet and telecom companies, that are participating in this data transfer in the NSA.

Radack: I consider this to be an unlawful order. While I am glad that we finally have something tangible to look at, this order came from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court. They have no jurisdiction to authorize domestic-to-domestic surveillance.

Binney: Not surprised, but it's documentation that can't be refuted.

Wiebe: It's formal proof of our suspicions.

Q: Even given the senior positions that you all were in, you had never actually seen one of these?

Drake: They're incredibly secret. It's a very close hold. ... It's a secret court with a secret appeals court. They are just not widely distributed, even in the government.

Q: What was your first reaction when you saw it?

Binney: Mine was that it's documentary evidence of what we have been saying all along, so they couldn't deny it.

Drake: For me, it was material evidence of an institutional crime that we now claim is criminal.

Binney: Which is still criminal.

Wiebe: It's criminal.

Q: Thomas Drake, you worked as a contractor for the NSA for about a decade before you went on staff there. Were you surprised that a 29-year-old contractor based in Hawaii was able to get access to the sort of information that he released?

Drake: It has nothing to do with being 29. It's just that we are in the Internet age and this is the digital age. So, so much of what we do both in private and in public goes across the Internet. Whether it's the public Internet or whether it's the dark side of the Internet today, it's all affected the same in terms of technology. ...

One of the critical roles in the systems is the system administrator. Someone has to maintain it. Someone has to keep it running. Someone has to maintain the contracts.

Binney: Part of his job as the system administrator, he was to maintain the system. Keep the databases running. Keep the communications working. Keep the programs that were interrogating them operating. So that meant he was like a super-user. He could go on the network or go into any file or any system and change it or add to it or whatever, just to make sure — because he would be responsible to get it back up and running if, in fact, it failed.

So that meant he had access to go in and put anything. That's why he said, I think, "I can even target the president or a judge." If he knew their phone numbers or attributes, he could insert them into the target list which would be distributed worldwide. And then it would be collected, yeah, that's right. As a super-user, he could do that.

Q: As he said, he could tap the president's phone?

Binney: As a super-user and manager of data in the data system, yes, they could go in and change anything.

Q: At a Senate hearing in March, Oregon Democratic Sen. Ron Wyden asked the director of national intelligence, James Clapper, if there was mass data collection of Americans. He said "no." Was that a lie?

Drake: This is incredible dissembling. We're talking about the oversight committee, unable to get a straight answer because if the straight answer was given it would reveal the perfidy that's actually going on inside the secret side of the government.

Q: What should Clapper have said?

Binney: He should have said, "I can't comment in an open forum."

Wiebe: Yeah, that's right.

Q: Does Congress provide effective oversight for these programs?

Radack: Congress has been a rubber stamp, basically, and the judicial branch has been basically shut down from hearing these lawsuits because every time they do they are told that the people who are challenging these programs either have no standing or (are covered by) the state secrets privilege, and the government says that they can't go forward. So the idea that we have robust checks and balances on this is a myth.

Binney: But the way it's set up now, it's a joke. I mean, it can't work the way it is because they have no real way of seeing into what these agencies are doing. They are totally dependent on the agencies briefing them on programs, telling them what they are doing. And as long as the agencies tell them, they will know. If they don't tell them, they don't know. And that's what's been going on here.

And the only way they really could correct that is to create billets on these committees and integrate people in these agencies so they can go around every day and watch what is happening and then feed back the truth as to what's going on, instead of the story that they get from the NSA or other agencies. ...

Even take the FISA court, for example. The judges signed that order. I mean, I am sure they (the FBI) swore on an affidavit to the judge, "These are the reasons why," but the judge has no foundation to challenge anything that they present to him. What information does the judge have to make a decision against them? I mean, he has absolutely nothing. So that's really not an oversight.

Radack: The proof is in the pudding. Last year alone, in 2012, they approved 1,856 applications and they denied none. And that is typical from everything that has happened in previous years. ... I know the government has been asserting that all of this is kosher and legitimate because the FISA court signed off on it. The FISA court is a secret court — operates in secret. There is only one side and has rarely disapproved anything.

Q: Do you think President Obama fully knows and understands what the NSA is doing?

Binney: No. I mean, it's obvious. I mean, the Congress doesn't either. I mean, they are all being told what I call techno-babble ... and they (lawmakers) don't really don't understand what the NSA does and how it operates. Even when they get briefings, they still don't understand.

Radack: Even for people in the know, I feel like Congress is being misled.

Binney: Bamboozled.

Radack: I call it perjury.

Q: What should Edward Snowden expect now?

Binney: Well, first of all, I think he should expect to be treated just like Bradley Manning (an Army private now being court-martialed for leaking documents to WikiLeaks). The U.S. government gets ahold of him, that's exactly the way he will be treated.

Q: He'll be prosecuted?

Binney: First tortured, then maybe even rendered and tortured and then incarcerated and then tried and incarcerated or even executed.

Wiebe: Now there is another possibility, that a few of the good people on Capitol Hill — the ones who say the threat is much greater than what we thought it was — will step forward and say give this man an honest day's hearing. You know what I mean. Let's get him up here. Ask him to verify, because if he is right — and all pointers are that he was — all he did was point to law-breaking. What is the crime of that?

Drake: But see, I am Exhibit No. 1. ...You know, I was charged with 10 felony counts. I was facing 35 years in prison. This is how far the state will go to punish you out of retaliation and reprisal and retribution. ... My life has been changed. It's been turned inside, upside down. I lived on the blunt end of the surveillance bubble. ... When you are faced essentially with the rest of your life in prison, you really begin to understand and appreciate more so than I ever have — in terms of four times I took the oath to support the Constitution — what those rights and freedoms really mean. ...

Believe me, they are going to put everything they have got to get him. I think there really is a risk. There is a risk he will eventually be pulled off the street.

Q: What do you mean?

Drake: Well, fear of rendition. There is going to be a team sent in.

Radack: We have already unleashed the full force of the entire executive branch against him and are now doing a worldwide manhunt to bring him in — something more akin to what we would do for Osama bin Laden. And I know for a fact, if we do get him, he would definitely face Espionage Act charges, as other people have who have exposed information of government wrongdoing. And I heard a number of people in Congress (say) he would also be charged with treason.

These are obviously the most serious offenses that can be leveled against an American. And the people who so far have faced them and have never intended to harm the U.S. or benefit the foreign nations have always wanted to go public. And they face severe consequences as a defector. That's why I understand why he is seeking asylum. I think he has a valid fear.

Wiebe: We are going to find out what kind of country we are, what have we become, what do we want to be.

Q: What would you say to him?

Binney: I would tell him to steer away from anything that isn't a public service — like talking about the ability of the U.S. government to hack into other countries or other people is not a public service. So that's kind of compromising capabilities and sources and methods, basically. That's getting away from the public service that he did initially. And those would be the acts that people would charge him with as clearly treason.

Drake: Well, I feel extraordinary kinship with him, given what I experienced at the hands of the government. And I would just tell him to ensure that he's got a support network that I hope is there for him and that he's got the lawyers necessary across the world who will defend him to the maximum extent possible and that he has a support-structure network in place. I will tell you, when you exit the surveillance-state system, it's a pretty lonely place — because it had its own form of security and your job and family and your social network. And all of a sudden, you are on the outside now in a significant way, and you have that laser beam of the surveillance state turning itself inside out to find and learn everything they can about you.

Wiebe: I think your savior in all of this is being able to honestly relate to the principles embedded in the Constitution that are guiding your behavior. That's where really — rubber meets the road, at that point.

Radack: I would thank him for taking such a huge personal risk and giving up so much of his life and possibly facing the loss of his life or spending it in jail. Thank him for doing that to try to help our country save it from itself in terms of exposing dark, illegal, unethical, unconstitutional conduct that is being done against millions and millions of people.

Drake: I actually salute him. I will say it right here. I actually salute him, given my experience over many, many years both inside and outside the system. Remember, I saw what he saw. I want to re-emphasize that. What he did was a magnificent act of civil disobedience. He's exposing the inner workings of the surveillance state. And it's in the public interest. It truly is.

Wiebe: Well, I don't want anyone to think that he had an alternative. No one should (think that). There is no path for intelligence-community whistle-blowers who know wrong is being done. There is none. It's a toss of the coin, and the odds are you are going to be hammered.

Q: Is there a way to collect this data that is consistent with the Fourth Amendment, the constitutional protection against unreasonable search and seizure?

Binney: Two basic principles you have to use. ... One is what I call the two-degree principle. If you have a terrorist talking to somebody in the United States — that's the first degree away from the terrorist. And that could apply to any country in the world. And then the second degree would be who that person in the United States talked to. So that becomes your zone of suspicion.

And the other one (principle) is you watch all the jihadi sites on the Web and who's visiting those jihadi sites, who has an interest in the philosophy being expressed there. And then you add those to your zone of suspicion.

Everybody else is innocent — I mean, you know, of terrorism, anyway.

Wiebe: Until they're somehow connected to this activity.

Binney: You pull in all the contents involving (that) zone of suspicion and you throw all the rest of it away. You can keep the attributes of all the communicants in the other parts of the world, the rest of the 7 billion people, right? And you can then encrypt it so that nobody can interrogate that base randomly.

That's the way of preventing this kind of random access by a contractor or by the FBI or any other DHS (Department of Homeland Security) or any other department of government. They couldn't go in and find anybody. You couldn't target your next-door neighbor. If you went in with his attributes, they're encrypted. ... So unless they are in the zone of suspicion, you won't see any content on anybody and you won't see any attributes in the clear. ...

It's all within our capabilities.

Drake: It's been within our capabilities for well over 12 years.

Wiebe: Bill and I worked on a government contract for a contractor not too far from here. And when we showed him the concept of how this privacy mechanism that Bill just described to you — the two degrees, the encryption and hiding of identities of innocent people — he said, "Nobody cares about that." I said, "What do you mean?"

This man was in a position to know a lot of government people in the contracting and buying of capabilities. He said. "Nobody cares about that."

Drake: This (kind of surveillance) is all unnecessary. It is important to note that the very best of American ingenuity and inventiveness, creativity, had solved the major challenge problem the NSA faced: How do you make sense of vast amounts of data, provide the information you need to protect the nation, while also protecting the fundamental rights that are enshrined in the Constitution?

The government in secret decided — willfully and deliberately — that that was no longer necessary after 9/11. So they said, you know what, hey, for the sake of security we are going to draw that line way, way over. And if it means eroding the liberties and freedoms of Americans and others, hey, so be it because that's what's most important. But this was done without the knowledge of the American people.

Q: Would it make a difference if contractors weren't used?

Wiebe: I don't think so. They are human beings. You know, look at what's going on with the IRS and the Tea Party. You know, there (are) human beings involved. We are all human beings — contractors, NSA government employees. We are all human beings. We undergo clearance checks, background investigations that are extensive and we are all colors, ages and religions. I mean this is part of the American fabric.

Binney: But when it comes to these data, the massive data information collecting on U.S. citizens and everything in the world they can, I guess the real problem comes with trust. That's really the issue. The government is asking for us to trust them.

It's not just the trust that you have to have in the government. It's the trust you have to have in the government employees, (that) they won't go in the database — they can see if their wife is cheating with the neighbor or something like that. You have to have all the trust of all the contractors who are parts of a contracting company who are looking at maybe other competitive bids or other competitors outside their — in their same area of business. And they might want to use that data for industrial intelligence gathering and use that against other companies in other countries even. So they can even go into a base and do some industrial espionage. So there is a lot of trust all around and the government, most importantly, the government has no way to check anything that those people are doing.

Q: So Snowden's ability to access information wasn't an exception?

Binney: And they didn't know he was doing (it). ... That's the point, right? ...They should be doing that automatically with code, so the instant when anyone goes into that base with a query that they are not supposed to be doing, they should be flagged immediately and denied access. And that could be done with code.

But the government is not doing that. So that's the greatest threat in this whole affair.

Wiebe: And the polygraph that is typically given to all people, government employees and contractors, never asks about integrity. Did you give an honest day's work for your pay? Do you feel like you are doing important and proper work? Those things never come up. It's always, "Do you have any association with a terrorist?" Well, everybody can pass those kinds of questions. But, unfortunately, we have a society that is quite willing to cheat.