Other people's money, and how the bankers use it 1914

CHAPTER 5 - WHAT PUBLICITY CAN DO

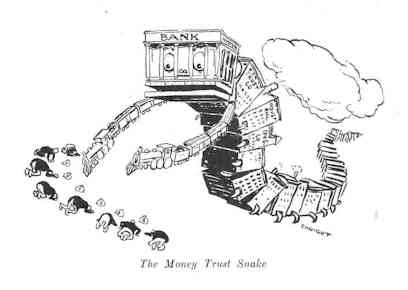

Illustration from Harper's Weekly December 20, 1913 by Walter J. Enright

- By Justice Louis Brandeis -

Publicity is justly commended as a remedy for social and industrial diseases. Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman. And publicity has already played an important part in the struggle against the Money Trust. The Pujo Committee has, in the disclosure of the facts concerning financial concentration, made a most important contribution toward attainment of the New Freedom. The battlefield has been surveyed and charted. The hostile forces have been located, counted and appraised. That was a necessary first step—and a long one—towards relief. The provisions in the Committee's bill concerning the incorporation of stock exchanges and the statement to be made in connection with the listing of securities would doubtless have a beneficent effect. But there should be a further call upon publicity for service. That potent force must, in the impending struggle, be utilized in many ways as a continuous remedial measure.

WEALTH

Combination and control of other people's money and of other people's businesses. These are the main factors in the development of the Money Trust. But the wealth of the investment banker is also a factor. And with the extraordinary growth of his wealth in recent years, the relative importance of wealth as a factor in financial concentration has grown steadily. It was wealth which enabled Mr. Morgan, in 1910, to pay $3,000,000 for $51,000 par value of the stock of the Equitable Life Insurance Society. His direct income from this investment was limited by law to less than one-eighth of one per cent. a year; but it gave legal control of $504,000,000 of assets. It was wealth which enabled the Morgan associates to buy, from the Equitable and the Mutual Life Insurance Company the stocks in the several banking institutions, which, merged in the Bankers' Trust Company and the Guaranty Trust Company, gave them control of $357,000,000 deposits. It was wealth which enabled Mr. Morgan to acquire his shares in the First National and National City banks, worth $21,000,000, through which he cemented the triple alliance with those institutions.

Now, how has this great wealth been accumulated? Some of it was natural accretion. Some of it is due to special opportunities for investment wisely availed of. Some of it is due to the vast extent of the bankers' operations. Then power breeds wealth as wealth breeds power. But a main cause of these large fortunes is the huge tolls taken by those who control the avenues to capital and to investors. There has been exacted as toll literally "all that the traffic will bear."

EXCESSIVE BANKERS' COMMISSIONS

The Pujo Committee was unfortunately prevented by lack of time from presenting to the country the evidence covering the amounts taken by the investment bankers as promoters' fees, underwriting commissions and profits. Nothing could have demonstrated so clearly the power exercised by the bankers, as a schedule showing the aggregate of these taxes levied within recent years. It would be well worth while now to reopen the Money Trust investigation merely to collect these data. But earlier investigations have disclosed some illuminating, though sporadic facts.

The syndicate which promoted the Steel Trust, took, as compensation for a few weeks' work, securities yielding $62,500,000 in cash; and of this, J. P. Morgan & Co. received for their services, as Syndicate Managers, $12,500,000, besides their share, as syndicate subscribers, in the remaining $50,000,000. The Morgan syndicate took for promoting the Tube Trust $20,000,000 common stock out of a total issue of $80,000,000 stock (preferred and common). Nor were monster commissions limited to trust promotions. More recently, bankers' syndicates have, in many instances, received for floating preferred stocks of recapitalized industrial concerns, one-third of all common stock issued, besides a considerable sum in cash. And for the sale of preferred stock of well established manufacturing concerns, cash commissions (or profits) of from 7 1/2 to 10 per cent. of the cash raised are often exacted. On bonds of high-class industrial concerns, bankers' commissions (or profits) of from 5 to 10 points have been common.

Nor have these heavy charges been confined to industrial concerns. Even railroad securities, supposedly of high grade, have been subjected to like burdens. At a time when the New Haven's credit was still unimpaired, J. P. Morgan & Co. took the New York, Westchester & Boston Railway first mortgage bonds, guaranteed by the New Haven at 92 1/2; and they were marketed at 96 1/4. They took the Portland Terminal Company bonds, guaranteed by the Maine Central Railroad—a corporation of unquestionable credit—at about 88, and these were marketed at 92.

A large part of these underwriting commissions is taken by the great banking houses, not for their services in selling the bonds, nor in assuming risks, but for securing others to sell the bonds and incur risks. Thus when the Interboro Railway—a most prosperous corporation—financed its recent $170,000,000 bond issue, J. P. Morgan & Co. received a 3 per cent. commission, that is, $5,100,000, practically for arranging that others should underwrite and sell the bonds.

The aggregate commissions or profits so taken by leading banking houses can only be conjectured, as the full amount of their transactions has not been disclosed, and the rate of commission or profit varies very widely. But the Pujo Committee has supplied some interesting data bearing upon the subject: Counting the issues of securities of interstate corporations only, J. P. Morgan & Co. directly procured the public marketing alone or in conjunction with others during the years 1902-1912, of $1,950,000,000. What the average commission or profit taken by J. P. Morgan & Co. was we do not know; but we do know that every one per cent. on that sum yields $19,500,000. Yet even that huge aggregate of $1,950,000,000 includes only a part of the securities on which commissions or profits were paid. It does not include any issue of an intrastate corporation. It does not include any securities privately marketed. It does not include any government, state or municipal bonds.

It is to exactions such as these that the wealth of the investment banker is in large part due. And since this wealth is an important factor in the creation of the power exercised by the Money Trust, we must endeavor to put an end to this improper wealth getting, as well as to improper combination. The Money Trust is so powerful and so firmly entrenched, that each of the sources of its undue power must be effectually stopped, if we would attain the New Freedom.

HOW SHALL EXCESSIVE CHARGES BE STOPPED?

The Pujo Committee recommends, as a remedy for such excessive charges, that interstate corporations be prohibited from entering into any agreements creating a sole fiscal agent to dispose of their security issues; that the issue of the securities of interstate railroads be placed under the supervision of the Interstate Commerce Commission; and that their securities should be disposed of only upon public or private competitive bids, or under regulations to be prescribed by the Commission with full powers of investigation that will discover and punish combinations which prevent competition in bidding. Some of the state public-service commissions now exercise such power; and it may possibly be wise to confer this power upon the interstate commission, although the recommendation of the Hadley Railroad Securities Commission are to the contrary. But the official regulation as proposed by the Pujo Committee would be confined to railroad corporations; and the new security issues of other corporations listed on the New York Stock Exchange have aggregated in the last five years $4,525,404,025, which is more than either the railroad or the municipal issues. Publicity offers, however, another and even more promising remedy: a method of regulating bankers' charges which would apply automatically to railroad, public-service and industrial corporations alike.

The question may be asked: Why have these excessive charges been submitted to? Corporations, which in the first instance bear the charges for capital, have, doubtless, submitted because of banker-control; exercised directly through interlocking directorates, or kindred relations, and indirectly through combinations among bankers to suppress competition. But why have the investors submitted, since ultimately all these charges are borne by the investors, except so far as corporations succeed in shifting the burden upon the community? The large army of small investors, constituting a substantial majority of all security buyers, are entirely free from banker control. Their submission is undoubtedly due, in part, to the fact that the bankers control the avenues to recognizedly safe investments almost as fully as they do the avenues to capital. But the investor's servility is due partly, also, to his ignorance of the facts. Is it not probable that, if each investor knew the extent to which the security he buys from the banker is diluted by excessive underwritings, commissions and profits, there would be a strike of capital against these unjust exactions?

THE STRIKE OF CAPITAL

A recent British experience supports this view. In a brief period last spring nine different issues, aggregating $135,840,000, were offered by syndicates on the London market, and on the average only about 10 per cent. of these loans was taken by the public. Money was "tight," but the rates of interest offered were very liberal, and no one doubted that the investors were well supplied with funds. The London Daily Mail presented an explanation:

"The long series of rebuffs to new loans at the hands of investors reached a climax in the ill success of the great Rothschild issue. It will remain a topic of financial discussion for many days, and many in the city are expressing the opinion that it may have a revolutionary effect upon the present system of loan issuing and underwriting. The question being discussed is that the public have become loth to subscribe for stock which they believe the underwriters can afford, by reason of the commission they receive, to sell subsequently at a lower price than the issue price, and that the Stock Exchange has begun to realize the public's attitude. The public sees in the underwriter not so much one who insures that the loan shall be subscribed in return for its commission as a middleman, who, as it were, has an opportunity of obtaining stock at a lower price than the public in order that he may pass it off at a profit subsequently. They prefer not to subscribe, but to await an opportunity of dividing that profit. They feel that if, when these issues were made, the stock were offered them at a more attractive price, there would be less need to pay the underwriters so high commissions. It is another practical protest, if indirect, against the existence of the middleman, which protest is one of the features of present-day finance."

PUBLICITY AS A REMEDY

Compel bankers when issuing securities to make public the commissions or profits they are receiving. Let every circular letter, prospectus or advertisement of a bond or stock show clearly what the banker received for his middleman-services, and what the bonds and stocks net the issuing corporation. That is knowledge to which both the existing security holder and the prospective purchaser is fairly entitled. If the bankers' compensation is reasonable, considering the skill and risk involved, there can be no objection to making it known. If it is not reasonable, the investor will "strike," as investors seem to have done recently in England.

Such disclosures of bankers' commissions or profits is demanded also for another reason: It will aid the investor in judging of the safety of the investment. In the marketing of securities there are two classes of risks: One is the risk whether the banker (or the corporation) will find ready purchasers for the bonds or stock at the issue price; the other whether the investor will get a good article. The maker of the security and the banker are interested chiefly in getting it sold at the issue price. The investor is interested chiefly in buying a good article. The small investor relies almost exclusively upon the banker for his knowledge and judgment as to the quality of the security; and it is this which makes his relation to the banker one of confidence. But at present, the investment banker occupies a position inconsistent with that relation. The bankers' compensation should, of course, vary according to the risk he assumes. Where there is a large risk that the bonds or stock will not be promptly sold at the issue price, the underwriting commission (that is the insurance premium) should be correspondingly large. But the banker ought not to be paid more for getting investors to assume a larger risk. In practice the banker gets the higher commission for underwriting the weaker security, on the ground that his own risk is greater. And the weaker the security, the greater is the banker's incentive to induce his customers to relieve him. Now the law should not undertake (except incidentally in connection with railroads and public-service corporations) to fix bankers' profits. And it should not seek to prevent investors from making bad bargains. But it is now recognized in the simplest merchandising, that there should be full disclosures. The archaic doctrine of caveat emptor is vanishing. The law has begun to require publicity in aid of fair dealing. The Federal Pure Food Law does not guarantee quality or prices; but it helps the buyer to judge of quality by requiring disclosure of ingredients. Among the most important facts to be learned for determining the real value of a security is the amount of water it contains. And any excessive amount paid to the banker for marketing a security is water. Require a full disclosure to the investor of the amount of commissions and profits paid; and not only will investors be put on their guard, but bankers' compensation will tend to adjust itself automatically to what is fair and reasonable. Excessive commissions—this form of unjustly acquired wealth—will in large part cease.

REAL DISCLOSURE

But the disclosure must be real. And it must be a disclosure to the investor. It will not suffice to require merely the filing of a statement of facts with the Commissioner of Corporations or with a score of other officials, federal and state. That would be almost as ineffective as if the Pure Food Law required a manufacturer merely to deposit with the Department a statement of ingredients, instead of requiring the label to tell the story. Nor would the filing of a full statement with the Stock Exchange, if incorporated, as provided by the Pujo Committee bill, be adequate.

To be effective, knowledge of the facts must be actually brought home to the investor, and this can best be done by requiring the facts to be stated in good, large type in every notice, circular, letter and advertisement inviting the investor to purchase. Compliance with this requirement should also be obligatory, and not something which the investor could waive. For the whole public is interested in putting an end to the bankers' exactions. England undertook, years ago, to protect its investors against the wiles of promoters, by requiring a somewhat similar disclosure; but the British act failed, in large measure of its purpose, partly because under it the statement of facts was filed only with a public official, and partly because the investor could waive the provision. And the British statute has now been changed in the latter respect.

DISCLOSE SYNDICATE PARTICULARS

The required publicity should also include a disclosure of all participants in an underwriting. It is a common incident of underwriting that no member of the syndicate shall sell at less than the syndicate price for a definite period, unless the syndicate is sooner dissolved. In other words, the bankers make by agreement, an artificial price. Often the agreement is probably illegal under the Sherman Anti-Trust Law. This price maintenance is, however, not necessarily objectionable. It may be entirely consistent with the general welfare, if the facts are made known. But disclosure should include a list of those participating in the underwriting so that the public may not be misled. The investor should know whether his adviser is disinterested.

Not long ago a member of a leading banking house was undertaking to justify a commission taken by his firm for floating a now favorite preferred stock of a manufacturing concern. The bankers took for their services $250,000 in cash, besides one-third of the common stock, amounting to about $2,000,000. "Of course," he said, "that would have been too much if we could have kept it all for ourselves; but we couldn’t. We had to divide up a large part. There were fifty-seven participants. Why, we had even to give $10,000 of stock to ———— (naming the president of a leading bank in the city where the business was located). He might some day have been asked what he thought of the stock. If he had shrugged his shoulders and said he didn't know, we might have lost many a customer for the stock. We had to give him $10,000 of the stock to teach him not to shrug his shoulders."

Think of the effectiveness with practical Americans of a statement like this:

A. B. & CO.

We have today secured substantial control of the successful machinery business heretofore conducted by -- at --, Illinois, which has been incorporated under the name of the Excelsior Manufacturing Company with a capital of $10,000,000, of which $5,000,000 is Preferred and $5,000,000 Common.

As we have a large clientele of confiding customers, we were able to secure from the owners an agreement for marketing the Preferred stock--we to fix a price which shall net the owners in cash $95 a share.

We offer this excellent stock to you at $100.75 per share. Our own commission or profit will be only a little over $5.00 per share, or say, $250,000 cash, besides $1,500,000 of the Common stock, which we received as a bonus. This cash and stock commission we are to divide in various proportions with the following participants in the underwriting syndicate:

C. D. & Co., New York

E. F. & Co., Boston

L. M. & Co., Philadelphia

I. K. & Co., New York

O. P. & Co., Chicago

Were such notices common, the investment bankers would "be worthy of their hire," for only reasonable compensation would ordinarily be taken.

For marketing the preferred stock, as in the case of Excelsior Manufacturing Co. referred to above, investment bankers were doubtless essential, and as middlemen they performed a useful service. But they used their strong position to make an excessive charge. There are, however, many cases where the banker's services can be altogether dispensed with; and where that is possible he should be eliminated, not only for economy's sake, but to break up financial concentration.

Go to the next chapter

Return to the table of contents

Other people's money, and how the bankers use it 1914

CHAPTER 4 - SERVE ONE MASTER ONLY

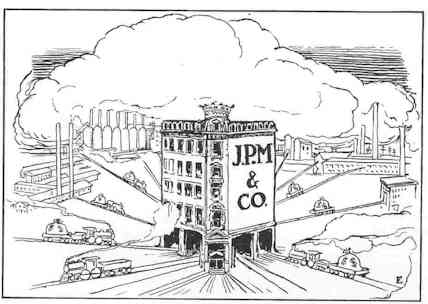

Illustration from Harper's Weekly December 13, 1913 by Walter J. Enright

- By Justice Louis Brandeis -

The Pujo Committee has presented the facts concerning the Money Trust so clearly that the conclusions appear inevitable. Their diagnosis discloses intense financial concentration and the means by which it is effected. Combination,—the intertwining of interests,—is shown to be the all-pervading vice of the present system. With a view to freeing industry, the Committee recommends the enactment of twenty-one specific remedial provisions. Most of these measures are wisely framed to meet some abuse disclosed by the evidence; and if all of these were adopted the Pujo legislation would undoubtedly alleviate present suffering and aid in arresting the disease. But many of the remedies proposed are "local" ones; and a cure is not possible, without treatment which is fundamental. Indeed, a major operation is necessary. This the Committee has hesitated to advise; although the fundamental treatment required is simple: "Serve one Master only."

The evils incident to interlocking directorates are, of course, fully recognized; but the prohibitions proposed in that respect are restricted to a very narrow sphere.

First: The Committee recognizes that potentially competing corporations should not have a common director;—but it restricts this prohibition to directors of national banks, saying:

"No officer or director of a national bank shall be an officer or director of any other bank or of any trust company or other financial or other corporation or institution, whether organized under state or federal law, that is authorized to receive money on deposit or that is engaged in the business of loaning money on collateral or in buying and selling securities except as in this section provided; and no person shall be an officer or director of any national bank who is a private banker or a member of a firm or partnership of bankers that is engaged in the business of receiving deposits: Provided, That such bank, trust company, financial institution, banker, or firm of bankers is located at or engaged in business at or in the same city, town, or village as that in which such national bank is located or engaged in business: Provided further, That a director of a national bank or a partner of such director may be an officer or director of not more than one trust company organized by the laws of the state in which such national bank is engaged in business and doing business at the same place."

Second: The Committee recognizes that a corporation should not make a contract in which one of the management has a private interest; but it restricts this prohibition (1) to national banks, and (2) to the officers, saying:

"No national bank shall lend or advance money or credit or purchase or discount any promissory note, draft, bill of exchange or other evidence of debt bearing the signature or indorsement of any of its officers or of any partnership of which such officer is a member, directly or indirectly, or of any corporation in which such officer owns or has a beneficial interest of upward of ten per centum of the capital stock, or lend or advance money or credit to, for or on behalf of any such officer or of any such partnership or corporation, or purchase any security from any such officer or of or from any partnership or corporation of which such officer is a member or in which he is financially interested, as herein specified, or of any corporation of which any of its officers is an officer at the time of such transaction."

Prohibitions of intertwining relations so restricted, however supplemented by other provisions, will not end financial concentration. The Money Trust snake will, at most, be scotched, not killed. The prohibition of a common director in potentially competing corporations should apply to state banks and trust companies, as well as to national banks; and it should apply to railroad and industrial corporations as fully as to banking institutions. The prohibition of corporate contracts in which one of the management has a private interest should apply to directors, as well as to officers, and to state banks and trust companies and to other classes of corporations, as well as to national banks. And, as will be hereafter shown, such broad legislation is within the power of Congress.

Let us examine this further:

THE PROHIBITION OF COMMON DIRECTORS IN POTENTIALLY COMPETING CORPORATIONS

1. National Banks. The objection to common directors, as applied to banking institutions, is clearly shown by the Pujo Committee.

"As the first and foremost step in applying a remedy, and also for reasons that seem to us conclusive, independently of that consideration, we recommend that interlocking directorates in potentially competing financial institutions be abolished and prohibited so far as lies in the power of Congress to bring about that result… When we find, as in a number of instances, the same man a director in half a dozen or more banks and trust companies all located in the same section of the same city, doing the same class of business and with a like set of associates similarly situated, all belonging to the same group and representing the same class of interests, all further pretense of competition is useless... If banks serving the same field are to be permitted to have common directors, genuine competition will be rendered impossible. Besides, this practice gives to such common directors the unfair advantage of knowing the affairs of borrowers in various banks, and thus affords endless opportunities for oppression."

This recommendation is in accordance with the legislation or practice of other countries. The Bank of England, the Bank of France, the National Bank of Belgium, and the leading banks of Scotland all exclude from their boards persons who are directors in other banks. By law, in Russia no person is allowed to be on the board of management of more than one bank.

The Committee's recommendation is also in harmony with laws enacted by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts more than a generation ago designed to curb financial concentration through the savings banks. Of the great wealth of Massachusetts a large part is represented by deposits in savings banks. These deposits are distributed among 194 different banks, located in 131 different cities and towns. These 194 banks are separate and distinct; not only in form, but in fact. In order that the banks may not be controlled by a few financiers, the Massachusetts law provides that no executive officer or trustee (director) of any savings bank can hold any office in any other savings bank. That statute was passed in 1876. A few years ago it was supplemented by providing that none of the executive officers of a savings bank could hold a similar office in any national bank. Massachusetts attempted thus to curb the power of the individual financier; and no disadvantages are discernible. When that Act was passed the aggregate deposits in its savings banks were $243,340,642; the number of deposit accounts 739,289; the average deposit to each person of the population $144. On November 1, 1912, the aggregate deposits were $838,635,097.85; the number of deposit accounts 2,200,917; the average deposit to each account $381.04. Massachusetts has shown that curbing the power of the few, at least in this respect, is entirely consistent with efficiency and with the prosperity of the whole people.

2. State Banks and Trust Companies. The reason for prohibiting common directors in banking institutions applies equally to national banks and to state banks including those trust companies which are essentially banks. In New York City there are 37 trust companies of which only 15 are members of the clearing house; but those 15 had on November 2, 1912, aggregate resources of $827,875,653. Indeed the Bankers' Trust Company with resources of $205,000,000, and the Guaranty Trust Company, with resources of $232,000,000, are among the most useful tools of the Money Trust. No bank in the country has larger deposits than the latter; and only one bank larger deposits than the former. If common directorships were permitted in state banks or such trust companies, the charters of leading national banks would doubtless soon be surrendered; and the institutions would elude federal control by re-incorporating under state laws.

The Pujo Committee has failed to apply the prohibition of common directorships in potentially competing banking institutions rigorously even to national banks. It permits the same man to be a director in one national bank and one trust company doing business in the same place. The proposed concession opens the door to grave dangers. In the first place the provision would permit the interlocking of any national bank not with one trust company only, but with as many trust companies as the bank has directors. For while under the Pujo bill no one can be a national bank director who is director in more than one such trust company, there is nothing to prevent each of the directors of a bank from becoming a director in a different trust company. The National Bank of Commerce of New York has a board of 38 directors. There are 37 trust companies in the City of New York. Thirty-seven of the 38 directors might each become a director of a different New York trust company: and thus 37 trust companies would be interlocked with the National Bank of Commerce, unless the other recommendation of the Pujo Committee limiting the number of directors to 13 were also adopted.

But even if the bill were amended so as to limit the possible interlocking of a bank to a single trust company, the wisdom of the concession would still be doubtful. It is true, as the Pujo Committee states, that "the business that may be transacted by" a trust company is of "a different character" from that properly transacted by a national bank. But the business actually conducted by a trust company is, at least in the East, quite similar; and the two classes of banking institutions have these vital elements in common: each is a bank of deposit, and each makes loans from its deposits. A private banker may also transact some business of a character different from that properly conducted by a bank; but by the terms of the Committee's bill a private banker engaged in the business of receiving deposits would be prevented from being a director of a national bank; and the reasons underlying that prohibition apply equally to trust companies and to private bankers.

3. Other Corporations. The interlocking of banking institutions is only one of the factors which have developed the Money Trust. The interlocking of other corporations has been an equally important element. And the prohibition of interlocking directorates should be extended to potentially competing corporations whatever the class; to life insurance companies, railroads and industrial companies, as well as banking institutions. The Pujo Committee has shown that Mr. George F. Baker is a common director in the six railroads which haul 80 per cent. of all anthracite marketed and own 88 per cent. of all anthracite deposits. The Morgan associates are the nexus between such supposedly competing railroads as the Northern Pacific and the Great Northern; the Southern, the Louisville & Nashville and the Atlantic Coast Line, and between partially competing industrials like the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company and the General Electric. The nexus between all the large potentially competing corporations must be severed, if the Money Trust is to be broken.

PROHIBITING CORPORATE CONTRACTS IN WHICH THE MANAGEMENT HAS A PRIVATE INTEREST

The principle of prohibiting corporate contracts in which the management has a private interest is applied, in the Pujo Committee's recommendations, only to national banks, and in them only to officers. All other corporations are to be permitted to continue the practice; and even in national banks the directors are to be free to have a conflicting private interest, except that they must not accept compensation for promoting a loan of bank funds nor participate in syndicates, promotions or underwriting of securities in which their banks may be interested as underwriters or owners or lenders thereon: that all loans or other transactions in which a director is interested shall be made in his own name; and shall be authorized only after ample notice to co-directors; and that the facts shall be spread upon the records of the corporation.

The Money Trust would not be disturbed by a prohibition limited to officers. Under a law of that character, financial control would continue to be exercised by the few without substantial impairment; but the power would be exerted through a somewhat different channel. Bank officers are appointees of the directors; and ordinarily their obedient servants. Individuals who, as bank officers, are now important factors in the financial concentration, would doubtless resign as officers and become merely directors. The loss of official salaries involved could be easily compensated. No member of the firm of J. P. Morgan & Co. is an officer in any one of the thirteen banking institutions with aggregate resources of $1,283,000,000, through which as directors they carry on their vast operations. A prohibition limited to officers would not affect the Morgan operations with these banking institutions. If there were minority representation on bank boards (which the Pujo Committee wisely advocates), such a provision might afford some protection to stockholders through the vigilance of the minority directors preventing the dominant directors using their power to the injury of the minority stockholders. But even then, the provision would not safeguard the public; and the primary purpose of Money Trust legislation is not to prevent directors from injuring stockholders; but to prevent their injuring the public through the intertwined control of the banks. No prohibition limited to officers will materially change this condition.

The prohibition of interlocking directorates, even if applied only to all banks and trust companies, would practically compel the Morgan representatives to resign from the directorates of the thirteen banking institutions with which they are connected, or from the directorates of all the railroads, express, steamship, public utility, manufacturing, and other corporations which do business with those banks and trust companies. Whether they resigned from the one or the other class of corporations, the endless chain would be broken into many pieces. And whether they retired or not, the Morgan power would obviously be greatly lessened: for if they did not retire, their field of operations would be greatly narrowed.

APPLY THE PRIVATE INTEREST PROHIBITION TO ALL KINDS OF CORPORATIONS

The creation of the Money Trust is due quite as much to the encroachment of the investment banker upon railroads, public service, industrial, and life-insurance companies, as to his control of banks and trust companies. Before the Money Trust can be broken, all these relations must be severed. And they cannot be severed unless corporations of each of these several classes are prevented from dealing with their own directors and with corporations in which those directors are interested. For instance: The most potent single source of J. P. Morgan & Co.'s power is the $162,500,000 deposits, including those of 78 interstate railroad, public-service and industrial corporations, which the Morgan firm is free to use as it sees fit. The proposed prohibition, even if applied to all banking institutions, would not affect directly this great source of Morgan power. If, however, the prohibition is made to include railroad, public-service, and industrial corporations, as well as banking institutions, members of J. P. Morgan & Co. will quickly retire from substantially all boards of directors.

APPLY THE PRIVATE INTEREST PROHIBITION TO STOCK HOLDING INTERESTS

The prohibition against one corporation entering into transactions with another corporation in which one of its directors is also interested, should apply even if his interest in the second corporation is merely that of stockholder. A conflict of interests in a director may be just as serious where he is a stockholder only in the second corporation, as if he were also a director.

One of the annoying petty monopolies, concerning which evidence was taken by the Pujo Committee, is the exclusive privilege granted to the American Bank Note Company by the New York Stock Exchange. A recent $60,000,000 issue of New York City bonds was denied listing on the Exchange, because the city refused to submit to an exaction of $55,800 by the American Company for engraving the bonds, when the New York Bank Note Company would do the work equally well for $44,500. As tending to explain this extraordinary monopoly, it was shown that men prominent in the financial world were stockholders in the American Company. Among the largest stockholders was Mr. Morgan, with 6,000 shares. No member of the Morgan firm was a director of the American Company; but there was sufficient influence exerted somehow to give the American Company the stock exchange monopoly.

The Pujo Committee, while failing to recommend that transactions in which a director has a private interest be prohibited, recognizes that a stockholder's interest of more than a certain size may be as potent an instrument of influence as a direct personal interest; for it recommends that:

"Borrowings, directly or indirectly by … any corporation of the stock of which he (a bank director) holds upwards of 10 per cent. from the bank of which he is such director, should only be permitted, on condition that notice shall have been given to his co-directors and that a full statement of the transaction shall be entered upon the minutes of the meeting at which such loan was authorized."

As shown above, the particular provision for notice affords no protection to the public; but if it did, its application ought to be extended to lesser stock holdings. Indeed it is difficult to fix a limit so low that financial interest will not influence action. Certainly a stock holding interest of a single director, much smaller than 10 per cent., might be most effective in inducing favors. Mr. Morgan’s stock holdings in the American Bank Note Company was only three per cent. The $6,000,000 investment of J. P. Morgan & Co. in the National City Bank represented only 6 per cent. of the bank's stock; and would undoubtedly have been effective, even if it had not been supplemented by the election of his son to the board of directors.

SPECIAL DISQUALIFICATIONS

The Stanley Committee, after investigation of the Steel Trust, concluded that the evils of interlocking directorates were so serious that representatives of certain industries which are largely dependent upon railroads should be absolutely prohibited from serving as railroad directors, officers or employees. It, therefore, proposed to disqualify as railroad director, officer or employee any person engaged in the business of manufacturing or selling railroad cars or locomotives, railroad rail or structural steel, or in mining and selling coal. The drastic Stanley bill, shows how great is the desire to do away with present abuses and to lessen the power of the Money Trust.

Directors, officers, and employees of banking institutions should, by a similar provision, be disqualified from acting as directors, officers or employees of life-insurance companies. The Armstrong investigation showed that life-insurance companies were in 1905 the most potent factor in financial concentration. Their power was exercised largely through the banks and trust companies which they controlled by stock ownership and their huge deposits. The Armstrong legislation directed life-insurance companies to sell their stocks. The Mutual Life and the Equitable did so in part. But the Morgan associates bought the stocks. And now, instead of the life-insurance companies controlling the banks and trust companies, the latter and the bankers control the life-insurance companies.

HOW THE PROHIBITION MAY BE LIMITED

The Money Trust cannot be destroyed unless all classes of corporations are included in the prohibition of interlocking directors and of transactions by corporations in which the management has a private interest. But it does not follow that the prohibition must apply to every corporation of each class. Certain exceptions are entirely consistent with merely protecting the public against the Money Trust; although protection of minority stockholders and business ethics demand that the rule prohibiting a corporation from making contracts in which a director has a private financial interest should be universal in its application. The number of corporations in the United States Dec. 31, 1912, was 305,336. Of these only 1610 have a capital of more than $5,000,000. Few corporations (other than banks) with a capital of less than $5,000,000 could appreciably affect general credit conditions either through their own operations or their affiliations. Corporations (other than banks) with capital resources of less than $5,000,000 might, therefore, be excluded from the scope of the statute for the present. The prohibition could also be limited so as not to apply to any industrial concern, regardless of the amount of capital and resources, doing only an intrastate business; as practically all large industrial corporations are engaged in interstate commerce. This would exclude some retail concerns and local jobbers and manufacturers not otherwise excluded from the operation of the act. Likewise banks and trust companies located in cities of less than 100,000 inhabitants might, if thought advisable, be excluded, for the present if their capital is less than $500,000, and their resources less than, say, $2,500,000. In larger cities even the smaller banking institutions should be subject to the law. Such exceptions should overcome any objection which might be raised that in some smaller cities, the prohibition of interlocking directorates would exclude from the bank directorates all the able business men of the community through fear of losing the opportunity of bank accommodations.

An exception should also be made, so as to permit interlocking directorates between a corporation and its proper subsidiaries. And the prohibition of transactions in which the management has a private interest should, of course, not apply to contracts, express or implied, for such services as are performed indiscriminately for the whole community by railroads and public service corporations, or for services, common to all customers, like the ordinary service of a bank for its depositors.

THE POWER OF CONGRESS

The question may be asked: Has Congress the power to impose these limitations upon the conduct of any business other than national banks? And if the power of Congress is so limited, will not the dominant financiers, upon the enactment of such a law, convert their national banks into state banks or trust companies, and thus escape from congressional control?

The answer to both questions is clear. Congress has ample power to impose such prohibitions upon practically all corporations, including state banks, trust companies and life insurance companies; and evasion may be made impossible. While Congress has not been granted power to regulate directly state banks, and trust or life insurance companies, or railroad, public-service and industrial corporations, except in respect to interstate commerce, it may do so indirectly by virtue either of its control of the mail privilege or through the taxing power.

Practically no business in the United States can be conducted without use of the mails; and Congress may in its reasonable discretion deny the use of the mail to any business which is conducted under conditions deemed by Congress to be injurious to the public welfare. Thus, Congress has no power directly to suppress lotteries; but it has indirectly suppressed them by denying, under heavy penalty, the use of the mail to lottery enterprises. Congress has no power to suppress directly business frauds; but it is constantly doing so indirectly by issuing fraud-orders denying the mail privilege. Congress has no direct power to require a newspaper to publish a list of its proprietors and the amount of its circulation, or to require it to mark paid-matter distinctly as advertising: But it has thus regulated the press, by denying the second-class mail privilege, to all publications which fail to comply with the requirements prescribed.

The taxing power has been restored to by Congress for like purposes: Congress has no power to regulate the manufacture of matches, or the use of oleomargarine; but it has suppressed the manufacture of the "white phosphorous" match and has greatly lessened the use of oleomargarine by imposing heavy taxes upon them. Congress has no power to prohibit, or to regulate directly the issue of bank notes by state banks, but it indirectly prohibited their issue by imposing a tax of ten per cent. upon any bank note issued by a state bank.

The power of Congress over interstate commerce has been similarly utilized. Congress cannot ordinarily provide compensation for accidents to employees or undertake directly to suppress prostitution; but it has, as an incident of regulating interstate commerce, enacted the Railroad Employers' Liability law and the White Slave Law; and it has full power over the instrumentalities of commerce, like the telegraph and the telephone.

As such exercise of congressional power has been common for, at least, half a century, Congress should not hesitate now to employ it where its exercise is urgently needed. For a comprehensive prohibition of interlocking directorates is an essential condition of our attaining the New Freedom. Such a law would involve a great change in the relation of the leading banks and bankers to other businesses. But it is the very purpose of Money Trust legislation to effect a great change; and unless it does so, the power of our financial oligarchy cannot be broken.

But though the enactment of such a law is essential to the emancipation of business, it will not alone restore industrial liberty. It must be supplemented by other remedial measures.

Go to the next chapter

Return to the table of contents

Other people's money, and how the bankers use it 1914

CHAPTER 3 - INTERLOCKING DIRECTORATES

Illustration from Harper's Weekly December 13, 1913 by Walter J. Enright

- By Justice Louis Brandeis

The practice of interlocking directorates is the root of many evils. It offends laws human and divine. Applied to rival corporations, it tends to the suppression of competition and to violation of the Sherman law. Applied to corporations which deal with each other, it tends to disloyalty and to violation of the fundamental law that no man can serve two masters. In either event it tends to inefficiency; for it removes incentive and destroys soundness of judgment. It is undemocratic, for it rejects the platform: "A fair field and no favors,"—substituting the pull of privilege for the push of manhood. It is the most potent instrument of the Money Trust. Break the control so exercised by the investment bankers over railroads, public-service and industrial corporations, over banks, life insurance and trust companies, and a long step will have been taken toward attainment of the New Freedom.

The term "Interlocking directorates" is here used in a broad sense as including all intertwined conflicting interests, whatever the form, and by whatever device effected. The objection extends alike to contracts of a corporation whether with one of its directors individually, or with a firm of which he is a member, or with another corporation in which he is interested as an officer or director or stockholder. The objection extends likewise to men holding the inconsistent position of director in two potentially competing corporations, even if those corporations do not actually deal with each other.

THE ENDLESS CHAIN

A single example will illustrate the vicious circle of control—the endless chain—through which our financial oligarchy now operates:

J. P. Morgan (or a partner), a director of the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad, causes that company to sell to J. P. Morgan & Co. an issue of bonds. J. P. Morgan & Co. borrow the money with which to pay for the bonds from the Guaranty Trust Company, of which Mr. Morgan (or a partner) is a director. J. P. Morgan & Co. sell the bonds to the Penn Mutual Life Insurance Company, of which Mr. Morgan (or a partner) is a director. The New Haven spends the proceeds of the bonds in purchasing steel rails from the United States Steel Corporation, of which Mr. Morgan (or a partner) is a director. The United States Steel Corporation spends the proceeds of the rails in purchasing electrical supplies from the General Electric Company, of which Mr. Morgan (or a partner) is a director. The General Electric sells supplies to the Western Union Telegraph Company, a subsidiary of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company; and in both Mr. Morgan (or a partner) is a director. The Telegraph Company has an exclusive wire contract with the Reading, of which Mr. Morgan (or a partner) is a director. The Reading buys its passenger cars from the Pullman Company, of which Mr. Morgan (or a partner) is a director. The Pullman Company buys (for local use) locomotives from the Baldwin Locomotive Company, of which Mr. Morgan (or a partner) is a director. The Reading, the General Electric, the Steel Corporation and the New Haven, like the Pullman, buy locomotives from the Baldwin Company. The Steel Corporation, the Telephone Company, the New Haven, the Reading, the Pullman and the Baldwin Companies, like the Western Union, buy electrical supplies from the General Electric. The Baldwin, the Pullman, the Reading, the Telephone, the Telegraph and the General Electric companies, like the New Haven, buy steel products from the Steel Corporation. Each and every one of the companies last named markets its securities through J. P. Morgan & Co.; each deposits its funds with J. P. Morgan & Co.; and with these funds of each, the firm enters upon further operations.

This specific illustration is in part suppositious; but it represents truthfully the operation of interlocking directorates. Only it must be multiplied many times and with many permutations to represent fully the extent to which the interests of a few men are intertwined. Instead of taking the New Haven as the railroad starting point in our example, the New York Central, the Santa Fe, the Southern, the Lehigh Valley, the Chicago and Great Western, the Erie or the Père Marquette might have been selected; instead of the Guaranty Trust Company as the banking reservoir, any one of a dozen other important banks or trust companies; instead of the Penn Mutual as purchaser of the bonds, other insurance companies; instead of the General Electric, its qualified competitor, the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company. The chain is indeed endless; for each controlled corporation is entwined with many others.

As the nexus of "Big Business" the Steel Corporation stands, of course, preeminent: The Stanley Committee showed that the few men who control the Steel Corporation, itself an owner of important railroads, are directors also in twenty-nine other railroad systems, with 126,000 miles of line (more than half the railroad mileage of the United States), and in important steamship companies. Through all these alliances and the huge traffic it controls, the Steel Corporation's influence pervades railroad and steamship companies—not as carriers only—but as the largest customers for steel. And its influence with users of steel extends much further. These same few men are also directors in twelve steel-using street railway systems, including some of the largest in the world. They are directors in forty machinery and similar steel-using manufacturing companies; in many gas, oil and water companies, extensive users of iron products; and in the great wire-using telephone and telegraph companies. The aggregate assets of these different corporations—through which these few men exert their influence over the business of the United States—exceeds sixteen billion dollars.

Obviously, interlocking directorates, and all that term implies, must be effectually prohibited before the freedom of American business can be regained. The prohibition will not be an innovation. It will merely give full legal sanction to the fundamental law of morals and of human nature: that "No man can serve two masters." The surprising fact is that a principle of equity so firmly rooted should have been departed from at all in dealing with corporations. For no rule of law has, in other connections, been more rigorously applied, than that which prohibits a trustee from occupying inconsistent positions, from dealing with himself, or from using his fiduciary position for personal profit. And a director of a corporation is as obviously a trustee as persons holding similar positions in an unincorporated association, or in a private trust estate, who are called specifically by that name. The Courts have recognized this fully.

Thus, the Court of Appeals of New York declared in an important case:

"While not technically trustees, for the title of the corporate property was in the corporation itself, they were charged with the duties and subject to the liabilities of trustees. Clothed with the power of controlling the property and managing the affairs of the corporation without let or hindrance, as to third persons, they were its agents; but as to the corporation itself equity holds them liable as trustees. While courts of law generally treat the directors as agents, courts of equity treat them as trustees, and hold them to a strict account for any breach of the trust relation. For all practical purposes they are trustees, when called upon in equity to account for their official conduct."

NULLIFYING THE LAW

But this wholesome rule of business, so clearly laid down, was practically nullified by courts in creating two unfortunate limitations, as concessions doubtless to the supposed needs of commerce.

First: Courts held valid contracts between a corporation and a director, or between two corporations with a common director, where it was shown that in making the contract, the corporation was represented by independent directors and that the vote of the interested director was unnecessary to carry the motion and his presence was not needed to constitute a quorum.

Second: Courts held that even where a common director participated actively in the making of a contract between two corporations, the contract was not absolutely void, but voidable only at the election of the corporation.

The first limitation ignored the rule of law that a beneficiary is entitled to disinterested advice from all his trustees, and not merely from some; and that a trustee may violate his trust by inaction as well as by action. It ignored, also, the laws of human nature, in assuming that the influence of a director is confined to the act of voting. Every one knows that the most effective work is done before any vote is taken, subtly, and without provable participation. Every one should know that the denial of minority representation on boards of directors has resulted in the domination of most corporations by one or two men; and in practically banishing all criticism of the dominant power. And even where the board is not so dominated, there is too often that "harmonious cooperation" among directors which secures for each, in his own line, a due share of the corporation's favors.

The second limitation—by which contracts, in the making of which the interested director participates actively, are held merely voidable instead of absolutely void—ignores the teachings of experience. To hold such contracts merely voidable has resulted practically in declaring them valid. It is the directors who control corporate action; and there is little reason to expect that any contract, entered into by a board with a fellow director, however unfair, would be subsequently avoided. Appeals from Philip drunk to Philip sober are not of frequent occurrence, nor very fruitful. But here we lack even an appealing party. Directors and the dominant stockholders would, of course, not appeal; and the minority stockholders have rarely the knowledge of facts which is essential to an effective appeal, whether it be made to the directors, to the whole body of stockholders, or to the courts. Besides, the financial burden and the risks incident to any attempt of individual stockholders to interfere with an existing management is ordinarily prohibitive. Proceedings to avoid contracts with directors are, therefore, seldom brought, except after a radical change in the membership of the board. And radical changes in a board's membership are rare. Indeed the Pujo Committee reports:

"None of the witnesses, (the leading American bankers testified) was able to name an instance in the history of the country in which the stockholders had succeeded in overthrowing an existing management in any large corporation. Nor does it appear that stockholders have ever even succeeded in so far as to secure the investigation of an existing management of a corporation to ascertain whether it has been well or honestly managed."

Mr. Max Pam proposed in the April, 1913, Harvard Law Review, that the government come to the aid of minority stockholders. He urged that the president of every corporation be required to report annually to the stockholders, and to state and federal officials every contract made by the company in which any director is interested; that the Attorney-General of the United States or the State investigate the same and take proper proceedings to set all such contracts aside and recover any damages suffered; or without disaffirming the contracts to recover from the interested directors the profits derived therefrom. And to this end also, that State and National Bank Examiners, State Superintendents of Insurance, and the Interstate Commerce Commission be directed to examine the records of every bank, trust company, insurance company, railroad company and every other corporation engaged in interstate commerce. Mr. Pam's views concerning interlocking directorates are entitled to careful study. As counsel prominently identified with the organization of trusts, he had for years full opportunity of weighing the advantages and disadvantages of "Big Business." His conviction that the practice of interlocking directorates is a menace to the public and demands drastic legislation, is significant. And much can be said in support of the specific measure which he proposes. But to be effective, the remedy must be fundamental and comprehensive.

THE ESSENTIALS OF PROTECTION

Protection to minority stockholders demands that corporations be prohibited absolutely from making contracts in which a director has a private interest, and that all such contracts be declared not voidable merely, but absolutely void.

In the case of railroads and public-service corporations (in contradistinction to private industrial companies), such prohibition is demanded, also, in the interests of the general public. For interlocking interests breed inefficiency and disloyalty; and the public pays, in higher rates or in poor service, a large part of the penalty for graft and inefficiency. Indeed, whether rates are adequate or excessive cannot be determined until it is known whether the gross earnings of the corporation are properly expended. For when a company's important contracts are made through directors who are interested on both sides, the common presumption that money spent has been properly spent does not prevail. And this is particularly true in railroading, where the company so often lacks effective competition in its own field.

But the compelling reason for prohibiting interlocking directorates is neither the protection of stockholders, nor the protection of the public from the incidents of inefficiency and graft. Conclusive evidence (if obtainable) that the practice of interlocking directorates benefited all stockholders and was the most efficient form of organization, would not remove the objections. For even more important than efficiency are industrial and political liberty; and these are imperiled by the Money Trust. Interlocking directorates must be prohibited, because it is impossible to break the Money Trust without putting an end to the practice in the larger corporations.

BANKS AS PUBLIC-SERVICE CORPORATIONS

The practice of interlocking directorates is peculiarly objectionable when applied to banks, because of the nature and functions of those institutions. Bank deposits are an important part of our currency system. They are almost as essential a factor in commerce as our railways. Receiving deposits and making loans therefrom should be treated by the law not as a private business, but as one of the public services. And recognizing it to be such, the law already regulates it in many ways. The function of a bank is to receive and to loan money. It has no more right than a common carrier to use its powers specifically to build up or to destroy other businesses. The granting or withholding of a loan should be determined, so far as concerns the borrower, solely by the interest rate and the risk involved; and not by favoritism or other considerations foreign to the banking function. Men may safely be allowed to grant or to deny loans of their own money to whomsoever they see fit, whatsoever their motive may be. But bank resources are, in the main, not owned by the stockholders nor by the directors. Nearly three-fourths of the aggregate resources of the thirty-four banking institutions in which the Morgan associates hold a predominant influence are represented by deposits. The dependence of commerce and industry upon bank deposits, as the common reservoir of quick capital is so complete, that deposit banking should be recognized as one of the businesses "affected with a public interest." And the general rule which forbids public-service corporations from making unjust discriminations or giving undue preference should be applied to the operations of such banks.

Senator Owen, Chairman of the Committee on Banking and Currency, said recently:

"My own judgment is that a bank is a public-utility institution and cannot be treated as a private affair, for the simple reason that the public is invited, under the safeguards of the government, to deposit its money with the bank, and the public has a right to have its interests safeguarded through organized authorities. The logic of this is beyond escape. All banks in the United States, public and private, should be treated as public-utility institutions, where they receive public deposits."

The directors and officers of banking institutions must, of course, be entrusted with wide discretion in the granting or denying of loans. But that discretion should be exercised, not only honestly as it affects stockholders, but also impartially as it affects the public. Mere honesty to the stockholders demands that the interests to be considered by the directors be the interests of all the stockholders; not the profit of the part of them who happen to be its directors. But the general welfare demands of the director, as trustee for the public, performance of a stricter duty. The fact that the granting of loans involves a delicate exercise of discretion makes it difficult to determine whether the rule of equality of treatment, which every public-service corporation owes, has been performed. But that difficulty merely emphasizes the importance of making absolute the rule that banks of deposit shall not make any loan nor engage in any transaction in which a director has a private interest. And we should bear this in mind: If privately-owned banks fail in the public duty to afford borrowers equality of opportunity, there will arise a demand for government-owned banks, which will become irresistible.

The statement of Mr. Justice Holmes of the Supreme Court of the United States, in the Oklahoma Bank case, is significant:

"We cannot say that the public interests to which we have adverted, and others, are not sufficient to warrant the State in taking the whole business of banking under its control. On the contrary we are of opinion that it may go on from regulation to prohibition except upon such conditions as it may prescribe."

OFFICIAL PRECEDENTS

Nor would the requirement that banks shall make no loan in which a director has a private interest impose undue hardships or restrictions upon bank directors. It might make a bank director dispose of some of his investments and refrain from making others; but it often happens that the holding of one office precludes a man from holding another, or compels him to dispose of certain financial interests.

A judge is disqualified from sitting in any case in which he has even the smallest financial interest; and most judges, in order to be free to act in any matters arising in their court, proceed, upon taking office, to dispose of all investments which could conceivably bias their judgment in any matter that might come before them. An Interstate Commerce Commissioner is prohibited from owning any bonds or stocks in any corporation subject to the jurisdiction of the Commission. It is a serious criminal offence for any executive officer of the federal government to transact government business with any corporation in the pecuniary profits of which he is directly or indirectly interested.

And the directors of our great banking institutions, as the ultimate judges of bank credit, exercise today a function no less important to the country's welfare than that of the judges of our courts, the interstate commerce commissioners, and departmental heads.

SCOPE OF THE PROHIBITION

In the proposals for legislation on this subject, four important questions are presented:

1. Shall the principle of prohibiting interlocking directorates in potentially competing corporations be applied to state banking institutions, as well as the national banks?

2. Shall it be applied to all kinds of corporations or only to banking institutions?

3. Shall the principle of prohibiting corporations from entering into transactions in which the management has a private interest be applied to both directors and officers or be confined in its application to officers only?

4. Shall the principle be applied so as to prohibit transactions with another corporation in which one of its directors is interested merely as a stockholder?

Go to the next chapter

Return to the table of contents

Other people's money, and how the bankers use it 1914

CHAPTER 2 - HOW THE COMBINERS COMBINE

Illustration from Harper's Weekly November 13, 1913 by Walter J. Enright

- By Justice Louis Brandeis

Among the allies, two New York banks—the National City and the First National—stand preeminent. They constitute, with the Morgan firm, the inner group of the Money Trust. Each of the two banks, like J. P. Morgan & Co., has huge resources. Each of the two banks, like the firm of J. P. Morgan & Co., has been dominated by a genius in combination. In the National City it is James Stillman; in the First National, George F. Baker. Each of these gentlemen was formerly President, and is now Chairman of the Board of Directors. The resources of the National City Bank (including its Siamese-twin security company) are about $300,000,000; those of the First National Bank (including its Siamese-twin security company) are about $200,000,000. The resources of the Morgan firm have not been disclosed. But it appears that they have available for their operations, also, huge deposits from their subjects; deposits reported as $162,500,000.

The private fortunes of the chief actors in the combination have not been ascertained. But sporadic evidence indicates how great are the possibilities of accumulation when one has the use of "other people's money." Mr. Morgan's wealth became proverbial. Of Mr. Stillman's many investments, only one was specifically referred to, as he was in Europe during the investigation, and did not testify. But that one is significant. His 47,498 shares in the National City Bank are worth about $18,000,000. Mr. Jacob H. Schiff aptly described this as "a very nice investment."

Of Mr. Baker's investments we know more, as he testified on many subjects. His 20,000 shares in the First National Bank are worth at least $20,000,000. His stocks in six other New York banks and trust companies are together worth about $3,000,000. The scale of his investment in railroads may be inferred from his former holdings in the Central Railroad of New Jersey. He was its largest stockholder—so large that with a few friends he held a majority of the $27,436,800 par value of outstanding stock, which the Reading bought at $160 a share. He is a director in 28 other railroad companies; and presumably a stockholder in, at least, as many. The full extent of his fortune was not inquired into, for that was not an issue in the investigation. But it is not surprising that Mr. Baker saw little need of new laws. When asked:

"You think everything is all right as it is in this world, do you not?"

He answered, "Pretty nearly."

RAMIFICATIONS OF POWER

But wealth expressed in figures gives a wholly inadequate picture of the allies' power. Their wealth is dynamic. It is wielded by geniuses in combination. It finds its proper expression in means of control. To comprehend the power of the allies we must try to visualize the ramifications through which the forces operate.

Mr. Baker is a director in 22 corporations having, with their many subsidiaries, aggregate resources or capitalization of $7,272,000,000. But the direct and visible power of the First National Bank, which Mr. Baker dominates, extends further. The Pujo report shows that its directors (including Mr. Baker's son) are directors in at least 27 other corporations with resources of $4,270,000,000. That is, the First National is represented in 49 corporations, with aggregate resources or capitalization of $11,542,000,000.

It may help to an appreciation of the allies’ power to name a few of the more prominent corporations in which, for instance, Mr. Baker's influence is exerted—visibly and directly—as voting trustee, executive committee man or simple director.

1. Banks, Trust, and Life Insurance Companies: First National Bank of New York; National Bank of Commerce; Farmers' Loan and Trust Company; Mutual Life Insurance Company.

2. Railroad Companies: New York Central Lines; New Haven, Reading, Erie, Lackawanna, Lehigh Valley, Southern, Northern Pacific, Chicago, Burlington & Quincy.

3. Public Service Corporations: American Telegraph & Telephone Company, Adams Express Company.

4. Industrial Corporations: United States Steel Corporation, Pullman Company.

Mr. Stillman is a director in only 7 corporations, with aggregate assets of $2,476,000,000; but the directors in the National City Bank, which he dominates, are directors in at least 41 other corporations which, with their subsidiaries, have an aggregate capitalization or resources of $10,564,000,000. The members of the firm of J. P, Morgan & Co., the acknowledged leader of the allied forces, hold 72 directorships in 47 of the largest corporations of the country.

The Pujo Committee finds that the members of J. P. Morgan & Co. and the directors of their controlled trust companies and of the First National and the National City Bank together hold:

"One hundred and eighteen directorships in 34 banks and trust companies having total resources of $2,679,000,000 and total deposits of $1,983,000,000.

"Thirty directorships in 10 insurance companies having total assets of $2,293,000,000.

"One hundred and five directorships in 32 transportation systems having a total capitalization of $11,784,000,000 and a total mileage (excluding express companies and steamship lines) of 150,200.

"Sixty-three directorships in 24 producing and trading corporations having a total capitalization of $3,339,000,000.

"Twenty-five directorships in 12 public-utility corporations having a total capitalization of $2,150,000,000.

"In all, 341 directorships in 112 corporations having aggregate resources or capitalization of $22,245,000,000"

TWENTY-TWO BILLION DOLLARS

Twenty-two billion dollars is a large sum—so large that we have difficulty in grasping its significance. The mind realizes size only through comparisons. With what can we compare twenty-two billions of dollars? Twenty-two billions of dollars is more than three times the assessed value of all the property, real and personal, in all New England. It is nearly three times the assessed value of all the real estate in the City of New York. It is more than twice the assessed value of all the property in the thirteen Southern states. It is more than the assessed value of all the property in the twenty-two states, north and south, lying west of the Mississippi River.

But the huge sum of twenty-two billion dollars is not large enough to include all the corporations to which the "influence" of the three allies, directly and visibly, extends, for

First: There are 56 other corporations (not included in the Pujo schedule) each with capital or resources of over $5,000,000, and aggregating nearly $1,350,000,000, in which the Morgan allies are represented according to the directories of directors.

Second: The Pujo schedule does not include any corporation with resources of less than $5,000,000. But these financial giants have shown their humility by becoming directors in many such. For instance, members of J. P. Morgan & Co., and directors in the National City Bank and the First National Bank are also directors in 158 such corporations. Available publications disclose the capitalization of only 38 of these, but those 38 aggregate $78,669,375.

Third: The Pujo schedule includes only the corporations in which the Morgan associates actually appear by name as directors. It does not include those in which they are represented by dummies, or otherwise. For instance, the Morgan influence certainly extends to the Kansas City Terminal Railway Company, for which they have marketed since 1910 (in connection with others) four issues aggregating $41,761,000. But no member of J. P. Morgan & Co., of the National City Bank, or of the First National Bank appears on the Kansas City Terminal directorate.

Fourth: The Pujo schedule does not include all the subsidiaries of the corporations scheduled. For instance, the capitalization of the New Haven System is given as $385,000,000. That sum represents the bond and stock capital of the New Haven Railroad. But the New Haven System comprises many controlled corporations whose capitalization is only to a slight extent included directly or indirectly in the New Haven Railroad balance sheet. The New Haven, like most large corporations, is a holding company also; and a holding company may control subsidiaries while owning but a small part of the latters' outstanding securities. Only the small part so held will be represented in the holding company's balance sheet. Thus, while the New Haven Railroad's capitalization is only $385,000,000—and that sum only appears in the Pujo schedule—the capitalization of the New Haven System, as shown by a chart submitted to the Committee, is over twice as great; namely, $849,000,000.

It is clear, therefore, that the $22,000,000,000, referred to by the Pujo Committee, understates the extent of concentration effected by the inner group of the Money Trust.

CEMENTING THE TRIPLE ALLIANCE

Care was taken by these builders of imperial power that their structure should be enduring. It has been buttressed on every side by joint ownerships and mutual stock holdings, as well as by close personal relationships; for directorships are ephemeral and may end with a new election. Mr. Morgan and his partners acquired one-sixth of the stock of the First National Bank, and made a $6,000,000 investment in the stock of the National City Bank. Then J. P. Morgan & Co., the National City, and the First National (or their dominant officers—Mr. Stillman and Mr. Baker) acquired together, by stock purchases and voting trusts, control of the National Bank of Commerce, with its $190,000,000 of resources; of the Chase National, with $125,000,000; of the Guaranty Trust Company, with $232,000,000; of the Bankers' Trust Company, with $205,000,000; and of a number of smaller, but important, financial institutions. They became joint voting trustees in great railroad systems; and finally (as if the allies were united into a single concern) loyal and efficient service in the banks—like that rendered by Mr. Davison and Mr. Lamont in the First National—was rewarded by promotion to membership in the firm of J. P. Morgan & Co.

THE PROVINCIAL ALLIES

Thus equipped and bound together, J. P. Morgan & Co., the National City and the First National easily dominated America's financial center, New York; for certain other important bankers, to be hereafter mentioned, were held in restraint by "gentleman's" agreements. The three allies dominated Philadelphia too; for the firm of Drexel & Co. is J. P. Morgan & Co. under another name. But there are two other important money centers in America, Boston and Chicago.

In Boston there are two large international banking houses—Lee, Higginson & Co., and Kidder, Peabody & Co.—both long established and rich; and each possessing an extensive, wealthy clientele of eager investors in bonds and stocks. Since 1907 each of these firms has purchased or underwritten (principally in conjunction with other bankers) about 100 different security issues of the greater interstate corporations, the issues of each banker amounting in the aggregate to over $1,000,000,000. Concentration of banking capital has proceeded even further in Boston than in New York. By successive consolidations the number of national banks has been reduced from 58 in 1898 to 19 in 1913. There are in Boston now also 23 trust companies.