The Georgia Guidestones 10 Masonic Commandments - The New World Order

- By Karl Fabricius - June 11, 2010

Standing in the remote location of Elbert County, Georgia resides what is known as the American Stonehenge, or the Georgia Guidestones. Purposely placed in nature’s grasp, undisturbed by city life, this massive monument has an alarming message to convey to the world. Although the message is a beautiful ideal, tracing its roots back to the concept of a Utopia, it also entails sinister prospects for the future of humanity.

The message is considered as the new 10 commandments for an age governed by reason. They read as follows:

01 – Maintain humanity under 500,000,000 in perpetual balance with nature.

02 – Guide reproduction wisely – improving fitness and diversity.

03 – Unite humanity with a living new language.

04 – Rule passion – faith – tradition – and all things with tempered reason.

05 – Protect people and nations with fair laws and just courts.

06 – Let all nations rule internally resolving external disputes in a world court.

07 – Avoid petty laws and useless officials.

08 – Balance personal rights with social duties.

09 – Prize truth – beauty – love – seeking harmony with the infinite.

10 – Be not a cancer on the earth – Leave room for nature.

The Precision of its Craft

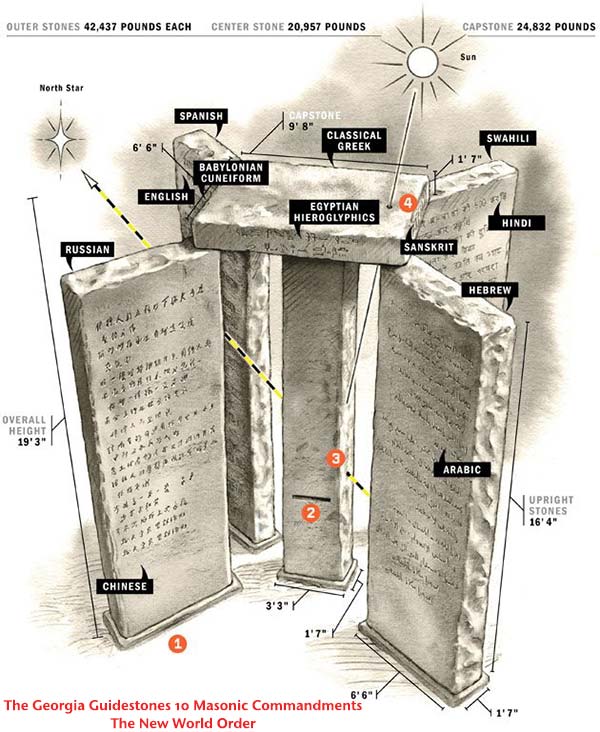

To prove its message is universal, and a driving pursuit since the very beginning of civilization, 4 ancient languages are engraved on the capstone, including Babylonian Cuneiform, Sanskrit, Egyptian Hieroglyphics, and Classical Greek. The message is also translated in 8 modern languages, from English to Swahili, appearing on the 4 slabs of granite rock underneath.

There is also a highly intricate astrological significance to the Georgia Guidestones, which make it that much more ominous. There are precise notches that parallel the movement of the sun, from its solstices to its equinoxes, while its outer core marks the lunar-year cycle. There is even a stargazing hole, which locates the North Star, Polaris. And lastly, during the noon hour, the sun is positioned right at the center of the capstone, a highly symbolic occult design to say the least.

Who Built the Georgia Guidestones?

The grand unveiling of the Georgia Guidestones occurred on March 22, 1980, more than 30 years ago. Yet, very little awareness of it really circulated, until maybe 2005 when the environmental movement became such a hot topic. Throughout this time, though no one knows who actually commissioned its construction; all that is known is that a man by the name of R.C. Christian wanted to build it. “R.C.” is most likely short for “the Rose and Cross” of Rosicrucianism, which is simply the precursor to what is known as Freemasonry today. Not surprisingly a tablet not too far from the monument reads, “Let these be guidestones to an Age of Reason”, which echoes the writing of one Thomas Paine, a prominent 18th century Freemason.

The Meaning of its Messages

Although the 10 “guides” are somewhat vague, they raise 5 main areas of interest:

5) Sustainable Development

4) New-Earth based Religion

3) World Government System

2) Eugenics or Transhumanism

1) Reducing the Population by 80-90%

There is no doubt environmental concerns should be a top priority for all of us. However, in this case it seems as though it can also be used as a method of enforcing various laws and taxes to hinder the general public, and little by little begin the reorganization of human life on this planet entirely. In fact, it is just a matter of time before the necessity for “stronger partnerships” to assure the preservation of the environment will cause an intentional unified body, or centralized power. However, one may argue that the United Nations is already a form of world government today.

A good example of controlling the population under the guise of safeguarding nature was put forth in the Earth Charter, and the subsequent Earth Summit of 1992, which gave rise to Agenda 21, the agenda for the 21st century. Coincidentally, one year after the Earth Summit, a book was published by a premiere think tank, a non-governmental organization, called the Club of Rome. The book is called “The First Global Revolution”, and on page 104, it states:

“The common enemy of humanity is man. In searching for a new enemy to unite us, we came up with the idea that pollution, the threat of global warming, water shortages, famine and the like would fit the bill. All these dangers are caused by human intervention, and it is only through changed attitudes and behavior that they can be overcome. …Democracy is not a panacea. It cannot organize everything and it is unaware of its own limits. Sacrilegious though this may sound, democracy is no longer well suited for the tasks ahead.”

The hope for a new golden age is forming. Whether the Georgia Guidestones is a signpost for its construction, or just a singular man’s dream, it should be looked at from every angle and with hardened thought.

It’s fitting too that the word “Utopia” literally means “no place”, because no civilization will ever reach perfection. Yet, it is obvious still that Mankind will continue to create a more sophisticated form of its prior creation, regardless of the implications it entails. After all, for those in power, the ends seem to always justify the means.

In that case, as empires rise and fall the never ending story will continue on, until perhaps a heaven on earth is attained. However, judging by the need to reduce the population, we all have to go through a certain type of hell before paradise is ultimately regained.

Life, Without True History, Would Be Sleep-Walking Through Absolute Misery And Sorrow

- By Bahram Maskanian - January 27, 2018

“Those who do not learn from their history are doomed to repeat it.” History is a guiding light, without which humanity will be doomed.! Particularly in today's world, where the nefarious parasite ruling class owns and controls all forms of media and press. Meaning that our ears and eyes have been shut. Blind and deaf folks will never be able to see and hear the truth, thus shall remain easily manipulated, blind, deaf and dumb voters.

Often times having conversation with others I noticed how majority of folks are completely detached from the fact that our life is a collection of historical memories, perspectives and records. Everyday through the practice of trial and error, we are forced by life experiences and wisdom to adopt new ideas and disguise the old, learn from the outcome, enhance our historical outlook and move on.

To learn from history is to begin learning from one’s own history of life continuum. Imagine what would happen if tomorrow you wake-up and don’t remember any of your past experiences and or life history.? The same is true about the much larger history and just as important as your own privet one. You must be alert at all times and keep in mind that there are many psychopath members and servants of the parasite ruling class at work to manipulate you and control your behavior, using false flag operations generated fear.

Fear has proven to be the most effective way of achieving that goal. When fearful, analytical mind is disabled, thus people believe any propaganda, regardless of how outlandish. Now let’s take a brief look at history of how fear was discovered to be a very effective tool for public control, shall we.? You see, the history of civilization (city dwelling) is over 12,000 years. During the first 9,000 years of known matriarchal rule, religion and religious mullahs were frowned upon, perceived as charlatans, fraudsters and no one paid any attention to them.

Until gradually the priesthood class, the mullahs began to observe the effects of fear in people, thus started to ponder, how people’s reaction to fear can be used against the public. Mullahs started with using the fears caused by the necessary, destructive natural weather events and the environmental incidents of the planet Earth to manipulate the masses. Obviously regardless of where one lives on planet Earth there are always natural geological and weather episodes. There are droughts and blinding sand storms in and around deserts. There are thunderstorms, hurricanes, earthquakes, and lightning in most geographical areas of planet Earth. There are monsoon rains and heavy flooding around the equator. There are volcano eruptions, spewing hot burning ashes and lava in the air and down over cities and people.

Each time when any of the said natural disasters occurred, the mullahs would blame the public, saying: “fear the lord, you are being punished for your sins, repent and accept the lord. I am here to bring you lord’s messages, that if you live your life as lord direct you through me, lord will forgive you. You must bring offerings and do what the lord tells you.!” Evidently natural disasters and weather events are not going to stop because some priest’s deceptive act. Each time when natural disasters would occur, the mullahs would warn people of the village that: “there are sinners among us, there are heretics among us, we must identify, remove and destroy them, followed by begging lord’s forgiveness.” And that is how the priests found and eliminated the nonbeliever opposition, in public square, by the most brutal means possible. - And sadly you should know by now that nothing has changed. The parasite ruling class of today in order to justify war, or mass murder and plunder, orchestrate mass hysteria and fear by using False Flag Operations, 9/11, Terrorism, Global Warming, Cold War, Bio-Terrorism, Economic Terrorism, etc.

The wealthy mullahs, receiving so many offerings, start tailoring bejeweled shoes, fancy cloaks, dresses and hats, decorated with gold, jewels and all kinds of symbols. thus elevating them-selves high and above the ignorant masses. Next came mullah’s uniform wearing swords men. The costume wearing mullahs soon became very powerful and demanding, start ordering the ignorant families to bring livestock: horses, cows, sheep, pigs, chicken, and even young innocent little boys and girls to the priests as offering to be blessed.! The dawn of normalizing child molestation and slavery.

With the accumulated wealth and power the public will not be allowed to address the parasite ruling class members by just name, thus titles were created, to coverup their true evil nature and conducts, thus deceive the masses, the parasite ruling class invented many ranking titles, which they have been bestowing on one another such as, but not limited to: "Royal Family, King, Queen, Prince, Princes, Emperor, Imperial, Majesty, Lord, Lady, Baron, Baroness, Earl, Count, Countess, Dame, Viscount, Viscountess, Marquis, Marchioness, Duke, Duchess, Sir, Excellency, Eminence, Holy Father, Holy See, Pope, Pastor, Bishop, Cardinal, Reverend, Archbishop, President and Doctor.!”

Uniform, wealth, power and titles made the parasite ruling class the long lasting eugenics mass murderers that they all are. The distinctive clothing worn by members of the organized cabal, religion, aristocrats and military is designed to instill fear, thus prompting undeserved respect in peoples’ minds for the tyrants, as it continues today.

“Power corrupts, absolute power corrupts absolutely.!” The wealthy powerful priests (mullahs), employed swords men, to enforce their barbaric rules. Soon the voluntary religious offerings were made into mandatory religious tax. The dawn of feudalism.! And those unfortunate folks who did not have the money to pay the religious tax, mullahs would confiscate their family farms, livestocks, even their children, to be used as sex slaves, and or servants, working for the house of worship, pleasing the manmade lord and enriching the priesthood class.

Consequently, priests became ambassadors of god on Earth. That is when the parasite ruling class were formed: consisting of aristocratic families, priesthood class, money changers, feudalism and imperialism. And to instill evermore fear in the hearts of ignorant masses, occasionally the Emperor and his priests would sent swords men out claiming that god had told the Emperor to kill all of the children born in that particular week, because one of them will grow up to become Lucifer. Brainwashed soldiers with their swords drawn would go to the villages and cut off the heads of the little angel of children, and any of the mothers or father’s who dared to try stopping the swords men, thus keeping the horror alive.

As if what was mentioned wasn’t enough, in many parts of planet earth, priests introduced the human sacrifice ritual. Innocent, young virgin girls would have been taken before god’s ambassador, the King, as the head priest, where either the King himself, or his head priest would tear open the live victim, the virgin girls chest and rip off her beating heart out, take a bite as the ignorant masses cheered with barbaric holler, while the king and the priest devour the virgin girl’s beating heart. In some volcanic regions the mullahs would throw the virgin girl, live down into the mouth of volcano to discourage volcanic eruption.

If every religious believer would read their hideous religious manual, written by psychopath men, humanity would be in much better shape. The parasite ruling class prostituted politicians, media and press deliberately create the illusion of Lucifer, they are reinforcing the religious manual’s idiotic narratives to legitimize all aspects of religions, while distracting people by using phrases such as: Satanic Order, and or Devil Worshipers, followed by some repulsive images of a beast with horns, to terrify the masses and shut you up, force you to stop asking questions and searching for answers, thus accepting the fictitious evil narratives as truth.

The mind-numbingly barbaric and stupid religious scam, imperialism and many other inhumane social and economic platforms are all fabricated, maintained and benefited by the psychopath parasite ruling class. Psychopaths are people who supposedly suffering from chronic mental disorder with abnormal and or violent social behavior. Psychopaths are without empathy, compassion and love, but fully conscience of their amoral, evil actions and behaviors. However there are also psychopaths by choice, whom are willing to do anything to gain wealth and power.

Real scientists whom are not in the pockets of the parasite ruling class have proven over and over again that all chronic illnesses can be cured using body’s own healing energy with meditation and healthy diet of fresh green vegetables and fresh fruits, free from all forms of alcohol, sodas, coffee, tobacco and processed foods.

“Psychopath, evil parasite ruling class, shall triumph only, if good people do nothing to stop them.!” - If you were wondering how.? - Simply disobey all that is harmful.!

Read and or download a free copy, everybody must read this amazing factual book.

Bloodlines of Illuminati - By: Fritz Springmeier - 1995

Alex Thomson - UK Column - Grand Jury Proceeding the Court of Public Opinion

METRIC UNITS & MEASUREMENTS

LENGTH | MASS | VOLUME | TIME | TEMPERATURE

| DECIMALS in MEASUREMENT | |

| Prefixes for units of length, volume, and mass in the metric system | |

| Prefix | Multiply by |

| milli- | 0.001 (1/1000) |

| centi- | 0.01 (1/100) |

| deci- | 0.1 (1/10) |

| deka- | 10 |

| hecto- | 100 |

| kilo- | 1000 |

| LENGTH |

| The standard unit of length in the metric system is the meter |

| 1 millimeter = 0.001 meter |

| 1 centimeter = 0.01 meter |

| 1 decimeter = 0.1 meter |

| 1 kilometer = 1000 meters |

| Abbreviations |

| 1 millimeter = 1 mm |

| 1 centimeter = 1 cm |

| 1 meter = 1 m |

| 1 decimeter = 1 dm |

| 1 kilometer = 1 km |

| FOR REFERENCE: One meter is about half the height of a very tall adult. A centimeter is a little less than the diameter of a dime A millimeter is about the thickness of a dime. |

| MASS |

| The standard unit of mass in the metric system is the gram. |

| 1 milligram = 0.001 gram |

| 1 centigram = 0.01 gram |

| 1 decigram = 0.1 gram |

| 1 kilogram = 1000 grams |

| Abbreviations |

| 1 milligram = 1 mg |

| 1 centigram = 1 cg |

| 1 decigram = 1 dg |

| 1 gram = 1 g |

| 1 kilogram = 1 kg |

| FOR REFERENCE: A gram is about the mass of a paper clip. One kilogram is about the mass of a liter of water. |

| VOLUME |

| The standard unit of volume in the metric system is the liter. |

| 1 milliliter = 0.001 liter |

| 1 centiliter = 0.01 liter |

| 1 deciliter = 0.1 liter |

| 1 kiloliter = 1000 liters |

| Abbreviations |

| 1 milliliter = 1 ml |

| 1 centiliter = 1 cl |

| 1 deciliter = 1 dl |

| 1 liter = 1 l |

| 1 kiloliter = 1 kl |

| FOR REFERENCE: One liter = 1000 cubic centimeters in volume. One liter is slightly more than a quart. One teaspoon equals about 5 milliliters. |

Slavery, Usury, Rent and Forced Taxation; The Four Pillars of Feudalism and or Capitalism

- By Bahram Maskanian

Feudalism, or capitalism, today's dominant social governing systems, masquerading as democratic governments in the U.S. and European colonizing, warmongering and oppressive countries have been put in place by a few criminal elites, claiming ownership of planet Earth and dominating the inhabitants of Earth as their own livestock, using the Semite men's evil bible as justification for their evil actions.

Feudalism, or capitalism and its four pillars of tyrannical rule: Slavery, Usury, Rent and Forced Taxation came to existence as the direct result of Semite men (Jews and Arabs of today) imposing the evil Judaism; by slaughtering innocent people and plundering their farmlands and all other belongings, starting three thousand years ago.

It took Semite men and their army of slave African men close to five hundred years to destroy the matriarchal civilization, based on just and fair system of "Democracy Cooperative", in Asia and North Africa, and replaced it with brutal slavery, usury, rent and forced taxation; thus the feudalism social governing system was born.

Countless millions of innocent people have been murdered by the evil Semite men to spread their barbaric Judaism through religious wars, slaughter and plunder. After the annihilation of millions of innocent people, the Semite men stole their belongings and farmlands, followed by capturing the remaining young victims to work as slaves, or forced to work the land as tenants and pay rent to the newly born criminal monarchy and aristocratic families for the very same land the vanquished people held in their community as "Cooperative Farms" for thousands of years.

To make matters worse, the working people, and tenant farmers were force to convert to Judaism and borrow money from the Semite money changers at exuberant interest, while they are also forced to pay religion and protection taxes to the monarchy and the aristocratic criminal families. Precisely the reason why the monarchs and the aristocratic families are and have been preserving and supporting the evil religions: Judaism and its two derivatives; Christianity and Islam. Had it not been for the support of the criminal elite, religion would have been forgotten by now.

Unlike what we are told, the human civilization expands over 12,000 years, where in the first 9,000 years of which people of planet Earth lived a happy, prospers and utopian life, at the matriarchal era. Before the fabrication of patriarchal religions by misogynist, pedophile, woman hating Semite men, through a coup d'état against the matriarchal social governing system and its utopian life, made possible by the ruling enlightened women.

Usury; is the criminal and illegal practice of lending money at unreasonably high rates of interest.

Feudalism; is the system of land grab by the criminal monarchy and aristocratic families and renting the very same farmland to peasants, obliged to pay rent, homage, his labor and a share of his produce in exchange for protection.

The criminal aristocratic feudalists, or capitalists families and their religious mullahs and establishments will not be able to rule without people's help and participation. We, the people must join together in civil disobedience, stop cooperating and taking part in all local and national elections. We must boycott all elections and convene constitutional convention to create a modern, just, and new constitution, otherwise nothing will ever change for better.