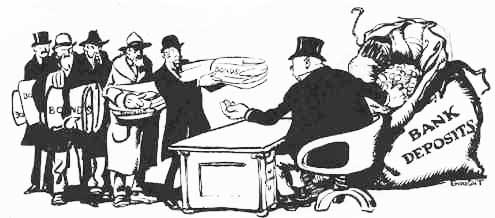

Other people's money, and how the bankers use it, 1914

CHAPTER 9 - THE FAILURE OF BANKER-MANAGEMENT

Illustration from Harper's Weekly December 27, 1913 by Walter J. Enright

- By Justice Louis Brandeis -

There is not one moral, but many, to be drawn from the Decline of the New Haven and the Fall of Mellen. That history offers texts for many sermons. It illustrates the Evils of Monopoly, the Curse of Bigness, the Futility of Lying, and the Pitfalls of Law-Breaking. But perhaps the most impressive lesson that it should teach to investors is the failure of banker-management.

BANKER CONTROL

For years J. P. Morgan & Co. were the fiscal agents of the New Haven. For years Mr. Morgan was the director of the Company. He gave to that property probably closer personal attention than to any other of his many interests. Stockholders' meetings are rarely interesting or important; and few indeed must have been the occasions when Mr. Morgan attended any stockholders' meeting of other companies in which he was a director. But it was his habit, when in America, to be present at meetings of the New Haven. In 1907, when the policy of monopolistic expansion was first challenged, and again at the meeting in 1909 (after Massachusetts had unwisely accorded its sanction to the Boston & Maine merger), Mr. Morgan himself moved the large increases of stock which were unanimously voted. Of course, he attended the important directors' meeting. His will was law. President Mellen indicated this in his statement before Interstate Commerce Commissioner Prouty, while discussing the New York, Westchester & Boston—the railroad without a terminal in New York, which cost the New Haven $1,500,000 a mile to acquire, and was then costing it, in operating deficits and interest charges, $100,000 a month to run:

"I am in a very embarrassing position, Mr. Commissioner, regarding the New York, Westchester & Boston. I have never been enthusiastic or at all optimistic of its being a good investment for our company in the present, or in the immediate future; but people in whom I had greater confidence than I have in myself thought it was wise and desirable; I yielded my judgment; indeed, I don't know that it would have made much difference whether I yielded or not."

THE BANKER'S RESPONSIBILITY

Bankers are credited with being a conservative force in the community. The tradition lingers that they are preeminently "safe and sane." And yet, the most grievous fault of this banker-managed railroad has been its financial recklessness—a fault that has already brought heavy losses to many thousands of small investors throughout New England for whom bankers are supposed to be natural guardians. In a community where its railroad stocks have for generations been deemed absolutely safe investments, the passing of the New Haven and of the Boston & Maine dividends after an unbroken dividend record of generations comes as a disaster.

This disaster is due mainly to enterprises outside the legitimate operation of these railroads; for no railroad company has equaled the New Haven in the quantity and extravagance of its outside enterprises. But it must be remembered, that neither the president of the New Haven nor any other railroad manager could engage in such transactions without the sanction of the Board of Directors. It is the directors, not Mr. Mellen, who should bear the responsibility.

Close scrutiny of the transactions discloses no justification. On the contrary, scrutiny serves only to make more clear the gravity of the errors committed. Not merely were recklessly extravagant acquisitions made in mad pursuit of monopoly; but the financial judgment, the financiering itself, was conspicuously bad. To pay for property several times what it is worth, to engage in grossly unwise enterprises, are errors of which no conservative directors should be found guilty; for perhaps the most important function of directors is to test the conclusions and curb by calm counsel the excessive zeal of too ambitious managers. But while we have no right to expect from bankers exceptionally good judgment in ordinary business matters; we do have a right to expect from them prudence, reasonably good financiering, and insistence upon straightforward accounting. And it is just the lack of these qualities in the New Haven management to which the severe criticism of the Interstate Commerce Commission is particularly directed.

Commissioner Prouty calls attention to the vast increase of capitalization. During the nine years beginning July 1, 1903, the capital of the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad Company itself increased from $93,000,000 to about $417,000,000 (excluding premiums). That fact alone would not convict the management of reckless financiering ; but the fact that so little of the new capital was represented by stock might well raise a question as to its conservativeness. For the indebtedness (including guaranties) was increased over twenty times (from about $14,000,000 to $300,000,000), while the stock outstanding in the hands of the public was not doubled ($80,000,000 to $158,000,000). Still, in these days of large things, even such growth of corporate liabilities might be consistent with "safe and sane management."

But what can be said in defense of the financial judgment of the banker-management under which these two railroads find themselves confronted, in the fateful year 1913, with a most disquieting floating indebtedness? On March 31, the New Haven had outstanding $43,000,000 in short-time notes; the Boston & Maine had then outstanding $24,500,000, which have been increased since to $27,000,000; and additional notes have been issued by several of its subsidiary lines. Mainly to meet its share of these loans, the New Haven, which before its great expansion could sell at par 3 1/2 per cent. bonds convertible into stock at $150 a share, was so eager to issue at par $67,500,000 of its 6 per cent. 20-year bonds convertible into stock as to agree to pay J. P. Morgan & Co. a 2 1/2 per cent. underwriting commission. True, money was "tight" then. But is it not very bad financiering to be so unprepared for the "tight" money market which had been long expected? Indeed, the New Haven's management, particularly, ought to have avoided such an error; for it committed a similar one in the "tight" money market of 1907-1908, when it had to sell at par $39,000,000 of its 6 per cent. 40-year bonds.

These huge short-time borrowings of the System were not due to unexpected emergencies or to their monetary conditions. They were of gradual growth. On June 30, 1910, the two companies owed in short-term notes only $10,180,364; by June 30, 1911, the amount had grown to $30,759,959; by June 30, 1912, to $45,395,000; and in 1913 to over $70,000,000. Of course the rate of interest on the loans increased also very largely. And these loans were incurred unnecessarily. They represent, in the main, not improvements on the New Haven or on the Boston & Maine Railroads, but money borrowed either to pay for stocks in other companies which these companies could not afford to buy, or to pay dividends which had not been earned.

In five years out of the last six the New Haven Railroad has, on its own showing, paid dividends in excess of the year's earnings; and the annual deficits disclosed would have been much larger if proper charges for depreciation of equipment and of steamships had been made. In each of the last three years, during which the New Haven had absolute control of the Boston & Maine, the latter paid out in dividends so much in excess of earnings that before April, 1913, the surplus accumulated in earlier years had been converted into a deficit.

Surely these facts show, at least, an extraordinary lack of financial prudence.

WHY BANKER-MANAGEMENT FAILED

Now, how can the failure of the banker-management of the New Haven be explained?

A few have questioned the ability; a few the integrity of the bankers. Commissioner Prouty attributed the mistakes made to the Company's pursuit of a transportation monopoly.

"The reason," says he, "is as apparent as the fact itself. The present management of that Company started out with the purpose of controlling the transportation facilities of New England. In the accomplishment of that purpose it bought what must be had and paid what must be paid. To this purpose and its attempted execution can be traced every one of these financial misfortunes and derelictions."

But it still remains to find the cause of the bad judgment exercised by the eminent banker-management in entering upon and in carrying out the policy of monopoly. For there were as grave errors in the execution of the policy of monopoly as in its adoption. Indeed, it was the aggregation of important errors of detail which compelled first the reduction, then the passing of dividends and which ultimately impaired the Company's credit.

The failure of the banker-management of the New Haven cannot be explained as the shortcomings of individuals. The failure was not accidental. It was not exceptional. It was the natural result of confusing the functions of banker and business man.

UNDIVIDED LOYALTY

The banker should be detached from the business for which he performs the banking service. This detachment is desirable, in the first place, in order to avoid conflict of interest. The relation of banker-directors to corporations which they finance has been a subject of just criticism. Their conflicting interests necessarily prevent single-minded devotion to the corporation. When a banker-director of a railroad decides as railroad man that it shall issue securities, and then sells them to himself as banker, fixing the price at which they are to be taken, there is necessarily grave danger that the interests of the railroad may suffer—suffer both through issuing of securities which ought not to be issued, and from selling them at a price less favorable to the company than should have been obtained. For it is ordinarily impossible for a banker-director to judge impartially between the corporation and himself. Even if he succeeded in being impartial, the relation would not conduce to the best interests of the company. The best bargains are made when buyer and seller are represented by different persons.

DETACHMENT AN ESSENTIAL

But the objection to banker-management does not rest wholly, or perhaps mainly, upon the importance of avoiding divided loyalty. A complete detachment of the banker from the corporation is necessary in order to secure for the railroad the benefit of the clearest financial judgment; for the banker's judgment will be necessarily clouded by participation in the management or by ultimate responsibility for the policy actually pursued. It is outside financial advice which the railroad needs.

Long ago it was recognized that "a man who is his own lawyer has a fool for a client." The essential reason for this is that soundness of judgment is easily obscured by self-interest. Similarly, it is not the proper function of the banker to construct, purchase, or operate railroads, or to engage in industrial enterprises. The proper function of the banker is to give to or to withhold credit from other concerns; to purchase or to refuse to purchase securities from other concerns; and to sell securities to other customers. The proper exercise of this function demands that the banker should be wholly detached from the concern whose credit or securities are under consideration. His decision to grant or to withhold credit, to purchase or not to purchase securities, involves passing judgment on the efficiency of the management or the soundness of the enterprise; and he ought not to occupy a position where in so doing he is passing judgment on himself. Of course detachment does not imply lack of knowledge. The banker should act only with full knowledge, just as a lawyer should act only with full knowledge. The banker who undertakes to make loans to or purchase securities from a railroad for sale to his other customers ought to have as full knowledge of its affairs as does its legal adviser. But the banker should not be, in any sense, his own client. He should not, in the capacity of banker, pass judgment upon the wisdom of his own plans or acts as railroad man.

Such a detached attitude on the part of the banker is demanded also in the interest of his other customers—the purchasers of corporate securities. The investment banker stands toward a large part of his customers in a position of trust, which should be fully recognized. The small investors, particularly the women, who are holding an ever-increasing proportion of our corporate securities, commonly buy on the recommendation of their bankers. The small investors do not, and in most cases cannot, ascertain for themselves the facts on which to base a proper judgment as to the soundness of securities offered. And even if these investors were furnished with the facts, they lack the business experience essential to forming a proper judgment. Such investors need and are entitled to have the bankers' advice, and obviously their unbiased advice; and the advice cannot be unbiased where the banker, as part of the corporation's management, has participated in the creation of the securities which are the subject of sale to the investor.

Is it conceivable that the great house of Morgan would have aided in providing the New Haven with the hundreds of millions so unwisely expended, if its judgment had not been clouded by participation in the New Haven's management?

Go to the next chapter

Return to the table of contents

Other people's money, and how the bankers use it 1914

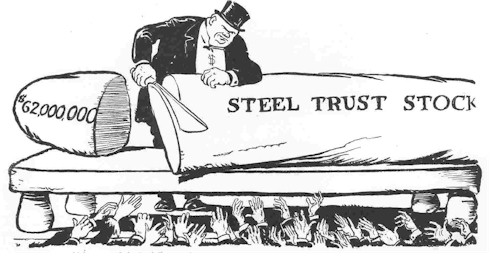

CHAPTER 8 - A CURSE OF BIGNESS

Illustration from Harper's Weekly December 20, 1913 by Walter J. Enright

- By Justice Louis Brandeis -

Bigness has been an important factor in the rise of the Money Trust: Big railroad systems, Big industrial trusts, big public service companies; and as instruments of these Big banks and Big trust companies. J. P. Morgan & Co. (in their letter of defence to the Pujo Committee) urge the needs of Big Business as the justification for financial concentration. They declare that what they euphemistically call "cooperation" is "simply a further result of the necessity for handling great transactions"; that "the country obviously requires not only the larger individual banks, but demands also that those banks shall cooperate to perform efficiently the country's business"; and that "a step backward along this line would mean a halt in industrial progress that would affect every wage-earner from the Atlantic to the Pacific." The phrase "great transactions" is used by the bankers apparently as meaning large corporate security issues. Leading bankers have undoubtedly cooperated during the last 15 years in floating some very large security issues, as well as many small ones. But relatively few large issues were made necessary by great improvements undertaken or by industrial development. Improvements and development ordinarily proceed slowly. For them, even where the enterprise involves large expenditures, a series of smaller issues is usually more appropriate than single large ones. This is particularly true in the East where the building of new railroads has practically ceased. The "great" security issues in which bankers have cooperated were, with relatively few exceptions, made either for the purpose of effecting combinations or, as a consequence of such combinations. Furthermore, the combinations which made necessary these large security issues or underwritings were, in most cases, either contrary to existing statute law, or contrary to laws recommended by the Interstate Commerce Commission, or contrary to the laws of business efficiency. So both the financial concentration and the combinations which they have served were, in the main, against the public interest. Size, we are told, is not a crime. But size may, at least, become noxious by reason of the means through which it was attained or the uses to which it is put. And it is size attained by combination, instead of natural growth, which has contributed so largely to our financial concentration. Let us examine a few cases.

THE HARRIMAN PACIFICS

J. P. Morgan & Co., in urging the "need of large banks and the cooperation of bankers," said: "The Attorney-General's recent approval of the Union Pacific settlement calls for a single commitment on the part of bankers of $126,000,000." This $126,000,000 "commitment" was not made to enable the Union Pacific to secure capital. On the contrary it was a guaranty that it would succeed in disposing of its Southern Pacific stock to that amount. And when it had disposed of that stock, it was confronted with the serious problem—what to do with the proceeds? This huge underwriting became necessary solely because the Union Pacific had violated the Sherman Law. It had acquired that amount of Southern Pacific stock illegally; and the Supreme Court of the United States finally decreed that the illegality cease. This same illegal purchase had been the occasion, twelve years earlier, of another "great transaction,"—the issue, of a $100,000,000 of Union Pacific bonds, which were sold to provide funds for acquiring this Southern Pacific and other stocks in violation of law. Bankers "cooperated" also to accomplish that.

UNION PACIFIC IMPROVEMENTS

The Union Pacific and its auxiliary lines (the Oregon Short Line, the Oregon Railway and Navigation and the Oregon-Washington Railroad) made, in the fourteen years, ending June 30, 1912, issues of securities aggregating $375,158,183 (of which $46,500,000 were refunded or redeemed) ; but the large security issues served mainly to supply funds for engaging in illegal combinations or stock speculation. The extraordinary improvements and additions that raised the Union Pacific Railroad to a high state of efficiency were provided mainly by the net earnings from the operation of its railroads. And note how great the improvements and additions were: Tracks were straightened, grades were lowered, bridges were rebuilt, heavy rails were laid, old equipment was replaced by new; and the cost of these was charged largely as operating expense. Additional equipment was added, new lines were built or acquired, increasing the system by 3524 miles of line, and still other improvements and betterments were made and charged to capital account. These expenditures aggregated $191,512,328. But it needed no "large security issues" to provide the capital thus wisely expended. The net earnings from the operations of these railroads were so large that nearly all these improvements and additions could have been made without issuing on the average more than $1,000,000 a year of additional securities for "new money," and the company still could have paid six per cent. dividends after 1906 (when that rate was adopted). For while $13,679,452 a year, on the average, was charged to Cost of Road and Equipment, the surplus net earnings and other funds would have yielded, on the average, $12,750,982 a year available for improvements and additions, without raising money on new security issues.

HOW THE SECURITY PROCEEDS WERE SPENT

The $375,000,000 securities (except to the extent of about $13,000,000 required for improvements, and the amounts applied for refunding and redemptions) were available to buy stocks and bonds of other companies. And some of the stocks so acquired were sold at large profits, providing further sums to be employed in stock purchases.

The $375,000,000 Union Pacific Lines security issues, therefore, were not needed to supply funds for Union Pacific improvements; nor did these issues supply funds for the improvement of any of the companies in which the Union Pacific invested (except that certain amounts were advanced later to aid in financing the Southern Pacific). They served, substantially, no purpose save to transfer the ownership of railroad stocks from one set of persons to another.

Here are some of the principal investments:

1. $91,657,500, in acquiring and financing the Southern Pacific.

2. $89,391,401, in acquiring the Northern Pacific stock and stock of the Northern Securities Co.

3. $45,466,960, in acquiring Baltimore & Ohio. stock.

4. $37,692,256, in acquiring Illinois Central stock.

5. $23,205,679, in acquiring New York Central stock.

6. $10,395,000, in acquiring Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe stock.

7. $8,946,781, in acquiring Chicago & Alton stock.

8. $11,610,187, in acquiring Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul stock.

9. $6,750,423, in acquiring Chicago & Northwestern stock.

10. $6,936,696, in acquiring Railroad Securities Co. stock (Illinois Central stock).

The immediate effect of these stock acquisitions, as stated by the Interstate Commerce Commission in 1907, was merely this: "Mr. Harriman may journey by steamship from New York to New Orleans, thence by rail to San Francisco, across the Pacific Ocean to China, and, returning by another route to the United States, may go to Ogden by any one of three rail lines, and thence to Kansas City or Omaha, without leaving the deck or platform of a carrier which he controls, and without duplicating any part of his journey. "He has further what appears to be a dominant control in the Illinois Central Railroad running directly north from the Gulf of Mexico to the Great Lakes, parallel to the Mississippi River; and two thousand miles west of the Mississippi River he controls the only line of railroad parallel to the Pacific Coast, and running from the Colorado River to the Mexican border…. "The testimony taken at this hearing shows that about fifty thousand square miles of territory in the State of Oregon, surrounded by the lines of the Oregon Short Line Railroad Company, the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company, and the Southern Pacific Company, is not developed. While the funds of those companies which could be used for that purpose are being invested in stocks like the New York Central and other lines having only a remote relation to the territory in which the Union Pacific System is located." Mr. Harriman succeeded in becoming director in 27 railroads with 39,354 miles of line; and they extended from the Atlantic to the Pacific; from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico.

THE AFTERMATH

On September 9, 1909, less than twelve years after Mr. Harriman first became a director in the Union Pacific, he died from overwork at the age of 61. But it was not death only that had set a limit to his achievements. The multiplicity of his interests prevented him from performing for his other railroads the great services that had won him a world-wide reputation as manager and rehabilitator of the Union Pacific and the Southern Pacific. Within a few months after Mr. Harriman's death the serious equipment scandal on the Illinois Central became public, culminating in the probable suicide of one of the vice-presidents of that company. The Chicago & Alton (in the management of which Mr. Harriman was prominent from 1899 to 1907, as President, Chairman of the Board, or Executive Committeeman), has never regained the prosperity it enjoyed before he and his associates acquired control. The Père Marquette has passed again into receiver's hands. Long before Mr. Harriman’s death the Union Pacific had disposed of its Northern Pacific stock, because the Supreme Court of the United States declared the Northern Securities Company illegal, and dissolved the Northern Pacific-Great Northern merger. Three years after his death, the Supreme Court of the United States ordered the Union Pacific-Southern Pacific merger dissolved. By a strange irony, the law has permitted the Union Pacific to reap large profits from its illegal transactions in Northern Pacific and Southern Pacific stocks. But many other stocks held "as investments" have entailed large losses. Stocks in the Illinois Central and other companies which cost the Union Pacific $129,894,991.72, had on November 15, 1913, a market value of only $87,851,500; showing a shrinkage of $42,043,491.72 and the average income from them, while held, was only about 4.30 per cent. on their cost.

A BANKER'S PARADISE

Kuhn, Loeb & Co. were the Union Pacific bankers. It was in pursuance of a promise which Mr. Jacob H. Schiff—the senior partner—had given, pending the reorganization, that Mr. Harriman first became a member of the Executive Committee in 1897. Thereafter combinations grew and crumbled, and there were vicissitudes in stock speculations. But the investment bankers prospered amazingly; and financial concentration proceeded without abatement. The bankers and their associates received the commissions paid for purchasing the stocks which the Supreme Court holds to have been acquired illegally—and have retained them. The bankers received commissions for underwriting the securities issued to raise the money with which to buy the stocks which the Supreme Court holds to have been illegally acquired, and have retained them. The bankers received commissions paid for floating securities of the controlled companies—while they were thus controlled in violation of law—and have, of course, retained them. Finally when, after years, a decree is entered to end the illegal combination, these same bankers are on hand to perform the services of undertaker—and receive further commissions for their banker-aid in enabling the law-breaking corporation to end its wrong doing and to comply with the decree of the Supreme Court. And yet, throughout nearly all this long period, both before and after Mr. Harriman's death, two partners in Kuhn, Loeb & Co. were directors or members of the executive committee of the Union Pacific; and as such must be deemed responsible with others for the illegal acts. Indeed, these bankers have not only received commissions for the underwritings of transactions accomplished, though illegal; they have received commissions also for merely agreeing to underwrite a "great transaction" which the authorities would not permit to be accomplished. The $126,000,000 underwriting (that "single commitment on the part of the bankers" to which J. P. Morgan & Co. refer as being called for by "the Attorney General's approval of the Union Pacific settlement") never became effective; because the Public Service Commission of California refused to approve the terms of settlement. But the Union Pacific, nevertheless, paid the Kuhn Loeb Syndicate a large underwriting fee for having been ready and willing "to serve" should the opportunity arise: and another underwriting commission was paid when the Southern Pacific stock was finally distributed, with the approval of Attorney General McReynolds, under the Court's decree. Thus the illegal purchase of Southern Pacific stock yielded directly four crops of commissions; two when it was acquired, and two when it was disposed of. And during the intervening period the illegally controlled Southern Pacific yielded many more commissions to the bankers. For the schedules filed with the Pujo Committee show that Kuhn, Loeb & Co. marketed, in addition to the Union Pacific securities above referred to, $334,000,000 of Southern Pacific and Central Pacific securities between 1903 and 1911. The aggregate amount of the commissions paid to these bankers in connection with Union Pacific-Southern Pacific transactions is not disclosed. It must have been very large; for not only were the transactions "great"; but the commissions were liberal. The Interstate Commerce Commission finds that bankers received about 5 per cent. on the purchase price for buying the first 750,000 shares of Southern Pacific stock; and the underwriting commission on the first $100,000,000 Union Pacific bonds issued to make that and other purchases was $5,000,000. How large the two underwriting commissions were which the Union Pacific paid in effecting the severance of this illegal merger, both the company and the bankers have declined to disclose. Furthermore the Interstate Commerce Commission showed, clearly, while investigating the Union Pacific's purchase of the Chicago & Alton stock, that the bankers' profits were by no means confined to commissions.

THE BURLINGTON

Such railroad combinations produce injury to the public far more serious than the heavy tax of bankers' commissions and profits. For in nearly every case the absorption into a great system of a theretofore independent railroad has involved the loss of financial independence to some community, property or men, who thereby become subjects or satellites of the Money Trust. The passing of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy, in 1901, to the Morgan associates, presents a striking example of this process. After the Union Pacific acquired the Southern Pacific stock in 1901, it sought control, also, of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy,—a most prosperous railroad, having then 7912 miles of line. The Great Northern and Northern Pacific recognized that Union Pacific control of the Burlington would exclude them from much of Illinois, Missouri, Wisconsin, Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, and South Dakota. The two northern roads, which were already closely allied with each other and with J. P. Morgan & Co., thereupon purchased for $215,227,000, of their joint 4 per cent. bonds, nearly all of the $109,324,000 (par value) outstanding Burlington stock. A struggle with the Union Pacific ensued which yielded soon to "harmonious coöperation." The Northern Securities Company was formed with $400,000,000 capital, thereby merging the Great Northern, the Northern Pacific and the Burlington, and joining the Harriman, Kuhn-Loeb, with the Morgan-Hill interests. Obviously neither the issue of $215,000,000 joint 4's, nor the issue of the $400,000,000 Northern Securities stock supplied one dollar of funds for improvements of, or additions to, any of the four great railroad systems concerned in these "large transactions." The sole effect of issuing $615,000,000 of securities was to transfer stock from one set of persons to another. And the resulting "harmonious cooperation" was soon interrupted by the government proceedings, which ended with the dissolution of the Northern Securities Company. But the evil done outlived the combination. The Burlington had passed forever from its independent Boston owners to the Morgan allies, who remain in control.

The Burlington—one of Boston's finest achievements—was the creation of John M. Forbes. He was a builder; not a combiner, or banker, or wizard of finance. He was a simple, hard-working business man. He had been a merchant in China at a time when China's trade was among America's big business. He had been connected with shipping and with manufacturers. He had the imagination of the great merchant; the patience and perseverance of the great manufacturer; the courage of the sea-farer; and the broad view of the statesman. Bold, but never reckless; scrupulously careful of other people's money, he was ready, after due weighing of chances, to risk his own in enterprises promising success. He was in the best sense of the term, a great adventurer. Thus equipped, Mr. Forbes entered, in 1852, upon those railroad enterprises which later developed into the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy. Largely with his own money and that of friends who confided in him, he built these railroads and carried them through the panic of '57, when the "great banking houses" of those days lacked courage to assume the burdens of a struggling ill-constructed line, staggering under financial difficulties. Under his wise management, and that of the men whom he trained, the little Burlington became a great system. It was "built on honor," and managed honorably. It weathered every other great financial crisis, as it did that of 1857. It reached maturity without a reorganization or the sacrifice of a single stockholder or bondholder.

Investment bankers had no place on the Burlington Board of Directors; nor had the banker-practice, of being on both sides of a bargain. "I am unwilling," said Mr. Forbes, early in his career, "to run the risk of having the imputation of buying from a company in which I am interested." About twenty years later he made his greatest fight to rescue the Burlington from the control of certain contractor-directors, whom his biographer, Mr. Pearson, describes as "persons of integrity, who had conceived that in their twofold capacity as contractors and directors they were fully able to deal with themselves justly." Mr. Forbes thought otherwise. The stockholders, whom he had aroused, sided with him and he won. Mr. Forbes was the pioneer among Boston railroad-builders. His example and his success inspired many others, for Boston was not lacking then in men who were builders, though some lacked his wisdom, and some his character. Her enterprise and capital constructed, in large part, the Union Pacific, the Atchison, the Mexican Central, the Wisconsin Central, and 24 other railroads in the West and South. One by one these western and southern railroads passed out of Boston control; the greater part of them into the control of the Morgan allies. Before the Burlington was surrendered, Boston had begun to lose her dominion, even, over the railroads of New England. In 1900 the Boston & Albany was leased to the New York Central,—a Morgan property; and a few years later, another Morgan railroad—the New Haven—acquired control of nearly every other transportation line in New England. Now nothing is left of Boston's railroad dominion in the West and South, except the Eastern Kentucky Railroad—a line 36 miles long; and her control of the railroads of Massachusetts is limited to the Grafton & Upton with 19 miles of line and the Boston, Revere Beach &Lynn,—a passenger road 13 miles long.

THE NEW HAVEN MONOPOLY

The rise of the New Haven Monopoly presents another striking example of combination as a developer of financial concentration; and it illustrates also the use to which "large security issues" are put. In 1892, when Mr. Morgan entered the New Haven directorate, it was a very prosperous little railroad with capital liabilities of $25,000,000 paying 10 per cent. dividends, and operating 508 miles of line. By 1899 the capitalization had grown to $80,477,600, but the aggregate mileage had also grown (mainly through merger or leases of other lines) to 2017. Fourteen years later, in 1913, when Mr. Morgan died and Mr. Mellen resigned, the mileage was 1997, just 20 miles less than in 1899; but the capital liabilities had increased to $425,935,000. Of course the business of the railroad had grown largely in those fourteen years; the road-bed was improved, bridges built, additional tracks added, and much equipment purchased; and for all this, new capital was needed; and additional issues were needed, also, because the company paid out in dividends more than it earned. But of the capital increase, over $200,000,000 was expended in the acquisition of the stock or other securities of some 121 other railroads, steamships, street railway-, electric-light-, gas- and water-companies. It was these outside properties, which made necessary the much discussed $67,000,000, 6 per cent. bond issue, as well as other large and expensive security issues. For in these fourteen years the improvements on the railroad including new equipment have cost, on the average, only $10,000,000 a year.

THE NEW HAVEN BANKERS

Few, if any, of those 121 companies which the New Haven acquired had, prior to their absorption by it, been financed by J. P. Morgan & Co. The needs of the Boston & Maine and Maine Central—the largest group—had, for generations, been met mainly through their own stockholders or through Boston banking houses. No investment banker had been a member of the Board of Directors of either of those companies. The New York, Ontario & Western—the next largest of the acquired railroads—had been financed in New York, but by persons apparently entirely independent of the Morgan allies. The smaller Connecticut railroads, now combined in the Central New England, had been financed mainly in Connecticut, or by independent New York bankers. The financing of the street railway companies had been done largely by individual financiers, or by small and independent bankers in the states or cities where the companies operate. Some of the steamship companies had been financed by their owners, some through independent bankers. As the result of the absorption of these 121 companies into the New Haven system, the financing of all these railroads, steamship companies, street railways, and other corporations, was made tributary to J. P. Morgan & Co.; and the independent bankers were eliminated or became satellites. And this financial concentration was proceeded with, although practically every one of these 121 companies was acquired by the New Haven in violation either of the state or federal law, or of both. Enforcement of the Sherman Act will doubtless result in dissolving this unwieldy illegal combination.

THE COAL MONOPOLY

Proof of the "cooperation" of the anthracite railroads is furnished by the ubiquitous presence of George F. Baker on the Board of Directors of the Reading, the Jersey Central, the Lackawanna, the Lehigh, the Erie, and the New York, Susquehanna & Western railroads, which together control nearly all the unmined anthracite as well as the actual tonnage. These roads have been an important factor in the development of the Money Trust. They are charged by the Department of Justice with fundamental violations both of the Sherman Law and of the Commodity clause of the Hepburn Act, which prohibits a railroad from carrying, in interstate trade, any commodity in which it has an interest, direct or indirect. Nearly every large issue of securities made in the last 14 years by any of these railroads (except the Erie), has been in connection with some act of combination. The combination of the anthracite railroads to suppress the construction, through the Temple Iron Company, of a competing coal road, has already been declared illegal by the Supreme Court of the United States. And in the bituminous coal field—the Kanawha District—the United States Circuit Court of Appeals has recently decreed that a similar combination by the Lake Shore, the Chesapeake & Ohio, and the Hocking Valley, be dissolved.

OTHER RAILROAD COMBINATIONS

The cases of the Union Pacific and of the New Haven are typical—not exceptional. Our railroad history presents numerous instances of large security issues made wholly or mainly to effect combinations. Some of these combinations have been proper as a means of securing natural feeders or extensions of main lines. But far more of them have been dictated by the desire to suppress active or potential competition; or by personal ambition or greed; or by the mistaken belief that efficiency grows with size. Thus the monstrous combination of the Rock Island and the St. Louis and San Francisco with over 14,000 miles of line is recognized now to have been obviously inefficient. It was severed voluntarily; but, had it not been, must have crumbled soon from inherent defects, if not as a result of proceedings under the Sherman law. Both systems are suffering now from the effects of this unwise combination; the Frisco, itself greatly overcombined, has paid the penalty in receivership. The Rock Island—a name once expressive of railroad efficiency and stability—has, through its excessive recapitalizations and combinations, become a football of speculators, and a source of great apprehension to confiding investors. The combination of the Cincinnati, Hamilton and Dayton, and the Père Marquette led to several receiverships.

There are, of course, other combinations which have not been disastrous to the owners of the railroads. But the fact that a railroad combination has not been disastrous does not necessarily justify it. The evil of the concentration of power is obvious; and as combination necessarily involves such concentration of power, the burden of justifying a combination should be placed upon those who seek to effect it. For instance, what public good has been subserved by allowing the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Company to issue $50,000,000 of securities to acquire control of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad—a widely extended, self-sufficient system of 5,000 miles, which, under the wise management of President Milton H. Smith had prospered continuously for many years before the acquisition; and which has gross earnings nearly twice as large as those of the Atlantic Coast Line. The legality of this combination has been recently challenged by Senator Lea; and an investigation by the Interstate Commerce Commission has been ordered.

THE PENNSYLVANIA

The reports from the Pennsylvania suggest the inquiry whether even this generally well-managed railroad is not suffering from excessive bigness. After 1898 it, too, bought, in large amounts, stocks in other railroads, including the Chesapeake & Ohio, the Baltimore & Ohio, and the Norfolk & Western. In 1906 it sold all its Chesapeake & Ohio stock, and a majority of its Baltimore & Ohio and Norfolk & Western holdings. Later it reversed its policy and resumed stock purchases, acquiring, among others, more Norfolk & Western and New York, New Haven & Hartford; and on Dec. 31, 1912, held securities valued at $331,909,154.32; of which, however, a large part represents Pennsylvania System securities. These securities (mostly stocks) constitute about one-third of the total assets of the Pennsylvania Railroad. The income on these securities in 1912 averaged only 4.30 per cent. on their valuation, while the Pennsylvania paid 6 per cent. on its stock. But the cost of carrying these foreign stocks is not limited to the difference between this income and outgo. To raise money on these stocks the Pennsylvania had to issue its own securities; and there is such a thing as an over-supply even of Pennsylvania securities. Over-supply of any stock depresses market values, and increases the cost to the Pennsylvania of raising new money. Recently came the welcome announcement of the management that it will dispose of its stocks in the anthracite coal mines; and it is intimated that it will divest itself also of other holdings in companies (like the Cambria Steel Company) extraneous to the business of railroading. This policy should be extended to include the disposition also of all stock in other railroads (like the Norfolk & Western, the Southern Pacific and the New Haven) which are not a part of the Pennsylvania System.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Six years ago the Interstate Commerce Commission, after investigating the Union Pacific transaction above referred to, recommended legislation to remedy the evils there disclosed. Upon concluding recently its investigation of the New Haven, the Commission repeated and amplified those recommendations, saying: "No student of the railroad problem can doubt that a most prolific source of financial disaster and complication to railroads in the past has been the desire and ability of railroad managers to engage in enterprises outside the legitimate operation of their railroads, especially by the acquisition of other railroads and their securities. The evil which results, first, to the investing public, and, finally, to the general public, cannot be corrected after the transaction has taken place; it can be easily and effectively prohibited. In our opinion the following propositions lie at the foundation of all adequate regulation of interstate railroads: 1. Every interstate railroad should be prohibited from spending money or incurring liability or acquiring property not in the operation of its railroad or in the legitimate improvement, extension, or development of that railroad. 2. No interstate railroad should be permitted to lease or purchase any other railroad, nor to acquire the stocks or securities of any other railroad, nor to guarantee the same, directl[y] or indirectly, without the approval of the federal government. 3. No stocks or bonds should be issued by an interstate railroad except for the purposes sanctioned in the two preceding paragraphs, and none should be issued without the approval of the federal government. It may be unwise to attempt to specify the price at which and the manner in which railroad stocks and securities shall be disposed of; but it is easy and safe to define the purpose for which they may be issued and to confine the expenditure of the money realized to that purpose." These recommendations are in substantial accord with those adopted by the National Association of Railway Commissioners. They should be enacted into law. And they should be supplemented by amendments of the Commodity Clause of the Hepburn Act, so that: 1. Railroads will be effectually prohibited from owning stock in corporations whose products they transport; 2. Such corporations will be prohibited from owning important stock holdings in railroads; and 3. Holding companies will be prohibited from controlling, as does the Reading, both a railroad and corporations whose commodities it transports. If laws such as these are enacted and duly enforced, we shall be protected from a recurrence of tragedies like the New Haven, of domestic scandals like the Chicago and Alton, and of international ones like the Frisco. We shall also escape from that inefficiency which is attendant upon excessive size. But what is far more important, we shall, by such legislation, remove a potent factor in financial concentration. Decentralization will begin. The liberated smaller units will find no difficulty in financing their needs without bowing the knee to money lords. And a long step will have been taken toward attainment of the New Freedom.

Go to the next chapter

Return to the table of contents

Other people's money, and how the bankers use it 1914

CHAPTER 7 - BIG MEN AND LITTLE BUSINESS

Illustration from Harper's Weekly December 20, 1913 by Walter J. Enright

- By Justice Louis Brandeis -

J. P. Morgan & Co. declare, in their letter to the Pujo Committee, that "practically all the railroad and industrial development of this country has taken place initially through the medium of the great banking houses." That statement is entirely unfounded in fact. On the contrary nearly every such contribution to our comfort and prosperity was "initiated" without their aid. The "great banking houses" came into relation with these enterprises, either after success had been attained, or upon "reorganization" after the possibility of success had been demonstrated, but the funds of the hardy pioneers, who had risked their all, were exhausted.

This is true of our early railroads, of our early street railways, and of the automobile; of the telegraph, the telephone and the wireless; of gas and oil; of harvesting machinery, and of our steel industry; of textile, paper and shoe industries; and of nearly every other important branch of manufacture. The initiation of each of these enterprises may properly be characterized as "great transactions"; and the men who contributed the financial aid and business management necessary for their introduction are entitled to share, equally with inventors, in our gratitude for what has been accomplished. But the instances are extremely rare where the original financing of such enterprises was undertaken by investment bankers, great or small. It was usually done by some common business man, accustomed to taking risks; or by some well-to-do friend of the inventor or pioneer, who was influenced largely by considerations other than money-getting. Here and there you will find that banker-aid was given; but usually in those cases it was a small local banking concern, not a "great banking house"' which helped to "initiate" the undertaking.

RAILROADS

We have come to associate the great bankers with railroads. But their part was not conspicuous in the early history of the Eastern railroads; and in the Middle West the experience was, to some extent, similar.

The Boston & Maine Railroad owns and leases 2,215 miles of line; but it is a composite of about 166 separate railroad companies. The New Haven Railroad owns and leases 1,996 miles of line; but it is a composite of 112 separate railroad companies. The necessary capital to build these little roads was gathered together, partly through state, county or municipal aid; partly from business men or landholders who sought to advance their special interests; partly from investors; and partly from well-to-do public-spirited men, who wished to promote the welfare of their particular communities. About seventy-five years after the first of these railroads was built, J. P. Morgan & Co. became fiscal agent for all of them by creating the New Haven-Boston & Maine monopoly.

STEAMSHIPS

The history of our steamship lines is similar. In 1807, Robert Fulton, with the financial aid of Robert R. Livingston, a judge and statesman—not a banker— demonstrated with the Claremont, that it was practicable to propel boats by steam. In 1833 the three Cunard brothers of Halifax and 232 other persons—stockholders of the Quebec and Halifax Steam Navigation Company—joined in supplying about $80,000 to build the Royal William, the first steamer to cross the Atlantic. In 1902, many years after individual enterprises had developed practically all the great ocean lines, J. P. Morgan & Co. floated the International Mercantile Marine with its $52,744,000 of 4 1/2 bonds, now selling at about 60, and $100,000,000 of stock (preferred and common) on which no dividend has ever been paid. It was just sixty-two years after the first regular line of transatlantic steamers—The Cunard—was founded that Mr. Morgan organized the Shipping Trust.

TELEGRAPH

The story of the telegraph is similar. The money for developing Morse's invention was supplied by his partner and co-worker, Alfred Vail. The initial line (from Washington to Baltimore) was built with an appropriation of $30,000 made by Congress in 1843. Sixty-six years later J. P. Morgan & Co. became bankers for the Western Union through financing its purchase by the American Telephone & Telegraph Company.

HARVESTING MACHINERY

Next to railroads and steamships, harvesting machinery has probably been the most potent factor in the development of America; and most important of the harvesting machines was Cyrus H. McCormick's reaper. That made it possible to increase the grain harvest twenty- or thirty-fold. No investment banker had any part in introducing this great business man's invention.

McCormick was without means; but William Butler Ogden, a railroad builder, ex-Mayor and leading citizen of Chicago, supplied $25,000 with which the first factory was built there in 1847. Fifty-five years later; J. P. Morgan & Co. performed the service of combining the five great harvester companies, and received a commission of $3,000,000. The concerns then consolidated as the International Harvester Company, with a capital stock of $120,000,000, had, despite their huge assets and earning power, been previously capitalized, in the aggregate, at only $10,500,000—strong evidence that in all the preceding years no investment banker had financed them. Indeed, McCormick was as able in business as in mechanical invention. Two years after Ogden paid him $25,000 for a half interest in the business, McCormick bought it back for $50,000; and thereafter, until his death in 1884, no one but members of the McCormick family had any interest in the business.

THE BANKER ERA

It may be urged that railroads and steamships, the telegraph and harvesting machinery were introduced before the accumulation of investment capital had developed the investment banker, and before America's "great banking houses" had been established; and that, consequently, it would be fairer to inquire what services bankers had rendered in connection with later industrial development. The firm of J. P. Morgan & Co. is fifty-five years old; Kuhn, Loeb & Co. fifty-six years old; Lee, Higginson & Co. over fifty years; and Kidder, Peabody & Co. forty-eight years; and yet the investment banker seems to have had almost as little part in "initiating" the great improvements of the last half century, as did bankers in the earlier period.

STEEL

The modern steel industry of America, is forty-five years old. The "great bankers" had no part in initiating it. Andrew Carnegie, then already a man of large means, introduced the Bessemer process in 1868. In the next thirty years our steel and iron industry increased greatly. By 1898 we had far outstripped all competitors. America's production about equalled the aggregate of England and Germany. We had also reduced costs so much that Europe talked of the "American Peril." It was 1898, when J. P. Morgan & Co. took their first step in forming the Steel Trust, by organizing the Federal Steel Company. Then followed the combination of the tube mills into an $80,000,000 corporation, J. P. Morgan & Co. taking for their syndicate services $20,000,000 of common stock. About the same time the consolidation of the bridge and structural works, the tin plate, the sheet steel, the hoop and other mills followed; and finally, in 1901, the Steel Trust was formed, with a capitalization of $1,402,000,000. These combinations came thirty years after the steel industry had been "initiated".

THE TELEPHONE

The telephone industry is less than forty years old. It is probably America's greatest contribution to industrial development. The bankers had no part in "initiating" it. The glory belongs to a simple, enthusiastic, warm-hearted, business man of Haverhill, Massachusetts, who was willing to risk his own money. H. N. Casson tells of this, most interestingly, in his "History of the Telephone":

"The only man who had money and dared to stake it on the future of the telephone was Thomas Sanders, and he did this not mainly for business reasons. Both he and Hubbard were attached to Bell primarily by sentiment, as Bell had removed the blight of dumbness from Sanders' little son, and was soon to marry Hubbard's daughter. Also, Sanders had no expectation, at first, that so much money would be needed. He was not rich. His entire business, which was that of cutting out soles for shoe manufacturers, was not at any time worth more than thirty-five thousand dollars. Yet, from 1874 to 1878, he had advanced nine-tenths of the money that was spent on the telephone. The first five thousand telephones, and more, were made with his money. And so many long, expensive months dragged by before any relief came to Sanders, that he was compelled, much against his will and his business judgment, to stretch his credit within an inch of the breaking-point to help Bell and the telephone. Desperately he signed note after note until he faced a total of one hundred and ten thousand dollars. If the new 'scientific toy' succeeded, which he often doubted, he would be the richest citizen in Haverhill; and if it failed, which he sorely feared, he would be a bankrupt. Sanders and Hubbard were leasing telephones two by two, to business men who previously had been using the private lines of the Western Union Telegraph Company. This great corporation was at this time their natural and inevitable enemy. It had swallowed most of its competitors, and was reaching out to monopolize all methods of communication by wire. The rosiest hope that shone in front of Sanders and Hubbard was that the Western Union might conclude to buy the Bell patents, just as it had already bought many others. In one moment of discouragement they had offered the telephone to President Orton, of the Western Union, for $100,000; and Orton had refused it. ‘What use,’ he asked pleasantly, ‘could this company make of an electrical toy?’

"But besides the operation of its own wires, the Western Union was supplying customers with various kinds of printing-telegraphs and dial-telegraphs, some of which could transmit sixty words a minute. These accurate instruments, it believed, could never be displaced by such a scientific oddity as the telephone, and it continued to believe this until one of its subsidiary companies—the Gold and Stock—reported that several of its machines had been superseded by telephones.

"At once the Western Union awoke from its indifference. Even this tiny nibbling at its business must be stopped. It took action quickly, and organized the ‘American Speaking-Telephone Company,’ and with $300,000 capital, and with three electrical inventors, Edison, Gray, and Dolbear, on its staff. With all the bulk of its great wealth and prestige, it swept down upon Bell and his little body-guard. It trampled upon Bell's patent with as little concern as an elephant can have when he tramples upon an ant's nest. To the complete bewilderment of Bell, it coolly announced that it had the only original telephone, and that it was ready to supply superior telephones with all the latest improvements made by the original inventors—Dolbear, Gray, and Edison.

"The result was strange and unexpected. The Bell group, instead of being driven from the field, were at once lifted to a higher level in the business world. And the Western Union, in the endeavor to protect its private lines, became involuntarily a ‘bell-wether’ to lead capitalists in the direction of the telephone.''

Even then, when financial aid came to the Bell enterprise, it was from capitalists, not from bankers, and among these capitalists was William H. Forbes (son of the builder of the Burlington) who became the first President of the Bell Telephone Company. That was in 1878. More than twenty years later, after the telephone had spread over the world, the great house of Morgan came into financial control of the property. The American Telephone & Telegraph Company was formed. The process of combination became active. Since January, 1900, its stock has increased from $25,886,300 to $344,606,400. In six years (1906 to 1912) the Morgan associates marketed about $300,000,000 bonds of that company or its subsidiaries. In that period the volume of business done by the telephone companies had, of course, grown greatly, and the plant had to be constantly increased; but the proceeds of these huge security issues were used, to a large extent, in effecting combinations; that is, in buying out telephone competitors; in buying control of the Western Union Telegraph Company; and in buying up outstanding stock interests in semi-independent Bell companies. It is these combinations which have led to the investigation of the Telephone Company by the Department of Justice; and they are, in large part, responsible for the movement to have the government take over the telephone business.

ELECTRICAL MACHINERY

The business of manufacturing electrical machinery and apparatus is only a little over thirty years old. J. P. Morgan & Co. became interested early in one branch of it; but their dominance of the business today is due, not to their "initiating" it, but to their effecting a combination, and organizing the General Electric Company in 1892. There were then three large electrical companies, the Thomson-Houston, the Edison and the Westinghouse, besides some small ones. The Thomson-Houston of Lynn, Massachusetts, was in many respects the leader, having been formed to introduce, among other things, important inventions of Prof. Elihu Thomson and Prof. Houston. Lynn is one of the principal shoe-manufacturing centers of America. It is within ten miles of State Street, Boston; but Thomson's early financial support came not from Boston bankers, but mainly from Lynn business men and investors; men active, energetic, and used to taking risks with their own money. Prominent among them was Charles A. Coffin, a shoe manufacturer, who became connected with the Thomson-Houston Company upon its organization and president of the General Electric when Mr. Morgan formed that company in 1892, by combining the Thomson-Houston and the Edison. To his continued service, supported by other Thomson-Houston men in high positions, the great prosperity of the company is, in large part, due. The two companies so combined controlled probably one-half of all electrical patents then existing in America; and certainly more than half of those which had any considerable value.

In 1896 the General Electric pooled its patents with the Westinghouse, and thus competition was further restricted. In 1903 the General Electric absorbed the Stanley Electric Company, its other large competitor; and became the largest manufacturer of electric apparatus and machinery in the world. In 1912 the resources of the Company were $131,942,144. It billed sales to the amount of $89,182,185. It employed directly over 60,000 persons,—more than a fourth as many as the Steel Trust. And it is protected against "undue" competition; for one of the Morgan partners has been a director, since 1909, in the Westinghouse; the only other large electrical machinery company in America.

THE AUTOMOBILE

The automobile industry is about twenty years old. It is now America's most prosperous business. When Henry B. Joy, President of the Packard Motor Car Company, was asked to what extent the bankers aided in "initiating" the automobile, he replied:

"It is the observable facts of history, it is also my experience of thirty years as a business man, banker, etc., that first the seer conceives an opportunity. He has faith in his almost second sight. He believes he can do something—develop a business—construct an industry—build a railroad—or Niagara Falls Power Company,—and make it pay !

"Now the human measure is not the actual physical construction, but the `make it pay'!

"A man raised the money in the late 90s and built a beet sugar factory in Michigan. Wiseacres said it was nonsense. He gathered together the money from his friends who would take a chance with him. He not only built the sugar factory (and there was never any doubt of his ability to do that) but he made it pay. The next year two more sugar factories were built, and were financially successful. These were built by private individuals of wealth, taking chances in the face of cries of doubting bankers and trust companies.

"Once demonstrated that the industry was a sound one financially and then bankers and trust companies would lend the new sugar companies which were speedily organized a large part of the necessary funds to construct and operate.

"The motor-car business was the same.

"When a few gentlemen followed me in my vision of the possibilities of the business, the banks and older business men (who in the main were the banks) said, ‘fools and their money soon to be parted’—etc., etc.

"Private capital at first establishes an industry, backs it through its troubles, and, if possible, wins financial success when banks would not lend a dollar of aid.

"The business once having proved to be practicable and financially successful, then do the banks lend aid to its needs."

Such also was the experience of the greatest of the many financial successes in the automobile industry—the Ford Motor Company.

HOW BANKERS ARREST DEVELOPMENT

But "great banking houses" have not merely failed to initiate industrial development; they have definitely arrested development because to them the creation of the trusts is largely due. The recital in the Memorial addressed to the President by the Investors' Guild in November, 1911, is significant:

"It is a well-known fact that modern trade combinations tend strongly toward constancy of process and products, and by their very nature are opposed to new processes and new products originated by independent inventors, and hence tend to restrain competition in the development and sale of patents and patent rights; and consequently tend to discourage independent inventive thought, to the great detriment of the nation, and with injustice to inventors whom the Constitution especially intended to encourage and protect in their rights."

And more specific was the testimony of the Engineering News:

"We are today something like five years behind Germany in iron and steel metallurgy, and such innovations as are being introduced by our iron and steel manufacturers are most of them merely following the lead set by foreigners years ago.

"We do not believe this is because American engineers are any less ingenious or original than those of Europe, though they may indeed be deficient in training and scientific education compared with those of Germany. We believe the main cause is the wholesale consolidation which has taken place in American industry. A huge organization is too clumsy to take up the development of an original idea. With the market closely controlled and profits certain by following standard methods, those who control our trusts do not want the bother of developing anything new.

"We instance metallurgy only by way of illustration: There are plenty of other fields of industry where exactly the same condition exists. We are building the same machines and using the same methods as a dozen years ago, and the real advances in the art are being made by European inventors and manufacturers."

To which President Wilson's statement may be added:

"I am not saying that all invention had been stopped by the growth of trusts, but I think it is perfectly clear that invention in many fields has been discouraged, that inventors have been prevented from reaping the full fruits of their ingenuity and industry, and that mankind has been deprived of many comforts and conveniences, as well as the opportunity of buying at lower prices.

"Do you know, have you had occasion to learn, that there is no hospitality for invention, now-a-days?"

TRUSTS AND FINANCIAL CONCENTRATION

The fact that industrial monopolies arrest development is more serious even than the direct burden imposed through extortionate prices. But the most harm-bearing incident of the trusts is their promotion of financial concentration. Industrial trusts feed the money trust. Practically every trust created has destroyed the financial independence of some communities and of many properties; for it has centered the financing of a large part of whole lines of business in New York, and this usually with one of a few banking houses. This is well illustrated by the Steel Trust, which is a trust of trusts; that is, the Steel Trust combines in one huge holding company the trusts previously formed in the different branches of the steel business. Thus the Tube Trust combined 17 tube mills, located in 16 different cities, scattered over 5 states and owned by 13 different companies. The wire trust combined 19 mills; the sheet steel trust 26; the bridge and structural trust 27; and the tin plate trust 36; all scattered similarly over many states. Finally these and other companies were formed into the United States Steel Corporation, combining 228 companies in all, located in 127 cities and towns, scattered over 18 states. Before the combinations were effected, nearly every one of these companies was owned largely by those who managed it, and had been financed, to a large extent, in the place, or, in the state, in which it was located. When the Steel Trust was formed all these concerns came under one management. Thereafter, the financing of each of these 228 corporations (and some which were later acquired) had to be done through or with the consent of J. P. Morgan & Co. That was the greatest step in financial concentration ever taken.

STOCK EXCHANGE INCIDENTS

The organization of trusts has served in another way to increase the power of the Money Trust. Few of the independent concerns out of which the trusts have been formed, were listed on the New York Stock Exchange; and few of them had financial offices in New York. Promoters of large corporations, whose stock is to be held by the public, and also investors, desire to have their securities listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Under the rules of the Exchange, no security can be so listed unless the corporation has a transfer agent and registrar in New York City. Furthermore, banker-directorships have contributed largely to the establishment of the financial offices of the trusts in New York City. That alone would tend to financial concentration. But the listing of the stock enhances the power of the Money Trust in another way. An industrial stock, once listed, frequently becomes the subject of active speculation; and speculation feeds the Money Trust indirectly in many ways. It draws the money of the country to New York. The New York bankers handle the loans of other people's money on the Stock Exchange; and members of the Stock Exchange receive large amounts from commissions. For instance: There are 5,084,952 shares of United States Steel common stock outstanding. But in the five years ending December 31, 1912, speculation in that stock was so extensive that there were sold on the Exchange an average of 29,380,888 shares a year; or nearly six times as much as there is Steel common in existence. Except where the transactions are by or for the brokers, sales on the Exchange involve the payment of twenty-five cents in commission for each share of stock sold; that is, twelve and one-half cents by the seller and twelve and one-half cents by the buyer. Thus the commission from the Steel common alone afforded a revenue averaging many millions a year. The Steel preferred stock is also much traded in; and there are 138 other industrials, largely trusts, listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

TRUST RAMIFICATIONS

But the potency of trusts as a factor in financial concentration is manifested in still other ways; notably through their ramifying operations. This is illustrated forcibly by the General Electric Company's control of water-power companies which has now been disclosed in an able report of the United States Bureau of Corporations:

"The extent of the General Electric influence is not fully revealed by its consolidated balance sheet. A very large number of corporations are connected with it through its subsidiaries and through corporations controlled by these subsidiaries or affiliated with them. There is a still wider circle of influence due to the fact that officers and directors of the General Electric Co. and its subsidiaries are also officers or directors of many other corporations, some of whose securities are owned by the General Electric Company.

"The General Electric Company holds in the first place all the common stock in three security holding companies: the United Electric Securities Co., the Electrical Securities Corporation, and the Electric Bond and Share Co. Directly and through these corporations and their officers the General Electric controls a large part of the water power of the United States.

. . ."The water-power companies in the General Electric group are found in 18 States. These 18 States have 2,325,757 commercial horsepower developed or under construction, and of this total the General Electric group includes 939,115 h. p. or 40.4 per cent. The greatest amount of power controlled by the companies in the General Electric group in any State is found in Washington. This is followed by New York, Pennsylvania, California, Montana, Iowa, Oregon, and Colorado. In five of the States shown in the table the water-power companies included in the General Electric group control more than 50 per cent. of the commercial power, developed and under construction. The percentage of power in the States included in the General Electric group ranges from a little less than 2 per cent. in Michigan to nearly 80 per cent. in Pennsylvania. In Colorado they control 72 per cent.; in New Hampshire 61 per cent.; in Oregon 58 per cent.; and in Washington 55 per cent.

"Besides the power developed and under construction water-power concerns included in the General Electric group own in the States shown in the table 641,600 h. p. undeveloped."

This water power control enables the General Electric group to control other public service corporations:

"The water-power companies subject to General Electric influence control the street railways in at least 16 cities and towns; the electric-light plants in 78 cities and towns; gas plants in 19 cities and towns; and are affiliated with the electric light and gas plants in other towns. Though many of these communities, particularly those served with light only, are small, several of them are the most important in the States where these water-power companies operate. The water-power companies in the General Electric group own, control, or are closely affiliated with, the street railways in Portland and Salem, Ore.; Spokane, Wash.; Great Falls, Mont. ; St. Louis, Mo. ; Winona, Minn.; Milwaukee and Racine, Wis.; Elmira, N. Y.; Asheville and Raleigh, N. C., and other relatively less important towns. The towns in which the lighting plants (electric or gas) are owned or controlled include Portland, Salem, Astoria, and other towns in Oregon; Bellingham and other towns in Washington; Butte, Great Falls, Bozeman and other towns in Montana; Leadville and Colorado Springs in Colorado; St. Louis, Mo. ; Milwaukee, Racine and several small towns in Wisconsin; Hudson and Rensselaer, N. Y.; Detroit, Mich. ; Asheville and Raleigh, N. C.; and in fact one or more towns in practically every community where developed water power is controlled by this group. In addition to the public-service corporations thus controlled by the water-power companies subject to General Electric influence, there are numerous public-service corporations in other municipalities that purchase power from the hydroelectric developments controlled by or affiliated with the General Electric Co. This is true of Denver, Colo., which has already been discussed. In Baltimore, Md., a water-power concern in the General Electric group, namely, the Pennsylvania Water & Power Co., sells 20,000 h. p. to the Consolidated Gas, Electric Light & Power Co., which controls the entire light and power business of that city. The power to operate all the electric street railway systems of Buffalo, N. Y., and vicinity, involving a trackage of approximately 375 miles, is supplied through a subsidiary of the Niagara Falls Power Co."

And the General Electric Company, through the financing of public service companies, exercises a like influence in communities where there is no water power:

"It, or its subsidiaries, has acquired control of or an interest in the public-service corporations of numerous cities where there is no water-power connection, and it is affiliated with still others by virtue of common directors… This vast network of relationship between hydro-electric corporations through prominent officers and directors of the largest manufacturer of electrical machinery and supplies in the United States is highly significant. . .

"It is possible that this relationship to such a large number of strong financial concerns, through common officers and directors, affords the General Electric Co. an advantage that may place rivals at a corresponding disadvantage. Whether or not this great financial power has been used to the particular disadvantage of any rival water-power concern is not so important as the fact that such power exists and that it might be so used at any time."

THE SHERMAN LAW

The Money Trust cannot be broken, if we allow its power to be constantly augmented. To break the Money Trust, we must stop that power at its source. The industrial trusts are among its most effective feeders. Those which are illegal should be dissolved. The creation of new ones should be prevented. To this end the Sherman Law should be supplemented both by providing more efficient judicial machinery, and by creating a commission with administrative functions to aid in enforcing the law. When that is done, another step will have been taken toward securing the New Freedom. But restrictive legislation alone will not suffice. We should bear in mind the admonition with which the Commissioner of Corporations closes his review of our water power development:

"There is . . . presented such a situation in water powers and other public utilities as might bring about at any time under a single management the control of a majority of the developed, water power in the United States and similar control over the public utilities in a vast number of cities and towns, including some of the most important in the country."

We should conserve all rights which the Federal Government and the States now have in our natural resources, and there should be a complete separation of our industries from railroads and public utilities.

Go to the next chapter

Return to the table of contents

Other people's money, and how the bankers use it 1914

CHAPTER 6 - WHERE THE BANKER IS SUPERFLUOUS

Illustration from Harper's Weekly December 27, 1913 by Walter J. Enright

- By Justice Louis Brandeis -

The abolition of interlocking directorates will greatly curtail the bankers' power by putting an end to many improper combinations. Publicity concerning bankers' commissions, profits and associates, will lend effective aid, particularly by curbing undue exactions. Many of the specific measures recommended by the Pujo Committee (some of them dealing with technical details) will go far toward correcting corporate and banking abuses; and thus tend to arrest financial concentration. But the investment banker has, within his legitimate province, acquired control so extensive as to menace the public welfare even where his business is properly conducted. If the New Freedom is to be attained, every proper means of lessening that power must be availed of. A simple and effective remedy, which can be widely applied, even without new legislation, lies near at hand: Eliminate the banker-middleman where he is superfluous.

Today practically all governments, states and municipalities pay toll to the banker on all bonds sold. Why should they? It is not because the banker is always needed. It is because the banker controls the only avenue through which the investor in bonds and stocks can ordinarily be reached. The banker has become the universal tax gatherer. True, the pro rata of taxes levied by him upon our state and city governments is less than that levied by him upon the corporations. But few states or cities escape payment of some such tax to the banker on every loan it makes. Even where the new issues of bonds are sold at public auction, or to the highest bidder on sealed proposals, the bankers' syndicates usually secure large blocks of the bonds which are sold to the people at a considerable profit. The middleman, even though unnecessary, collects his tribute.