Hurricane Sandy - A Fierce and Devastating Wake-up Call

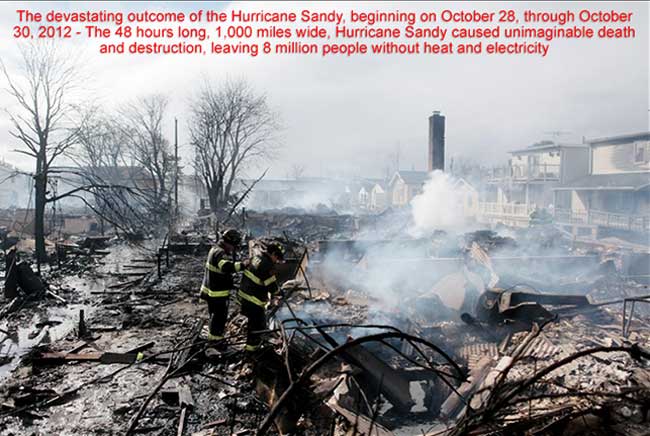

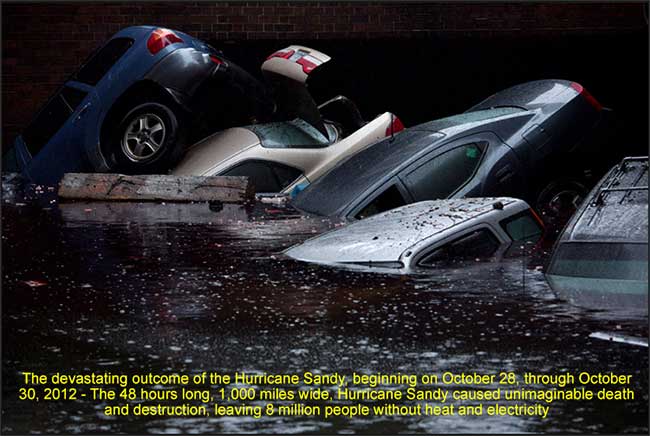

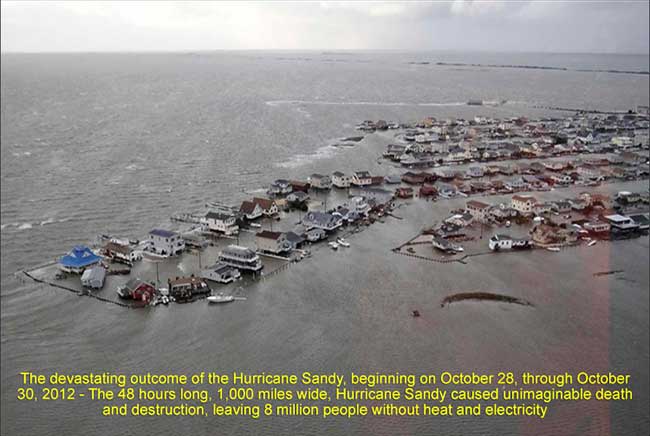

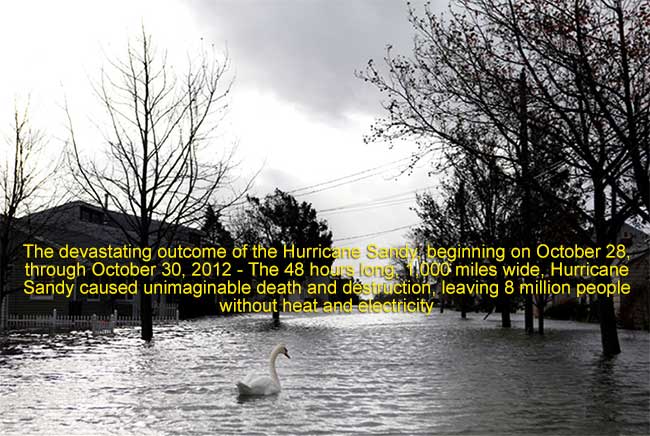

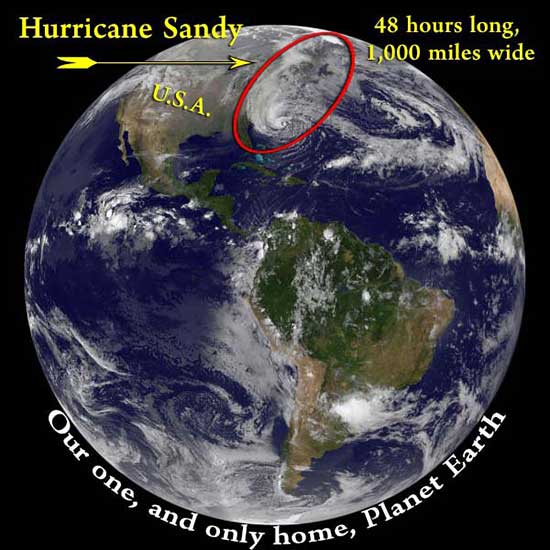

The devastating outcome of the Hurricane Sandy, beginning on October 28, through October 30, 2012 - The 48 hours long, 1,000 miles wide, Hurricane Sandy caused unimaginable death and destruction, leaving 8 million people without heat and electricity.

Hurricane Sandy is just the beginning of more intense and devastating climactic changes to come. - But it doesn’t have to be this way. - We, the humanity have many other viable choices of safe, environmentally friendly and sustainable means of generating our own power utilizing New Energy.

Hurricane Sandy - A Far-Reaching System That Leaves 8 Million Without Power

- By JOHN SCHWARTZ - The New York Times - October 30, 2012

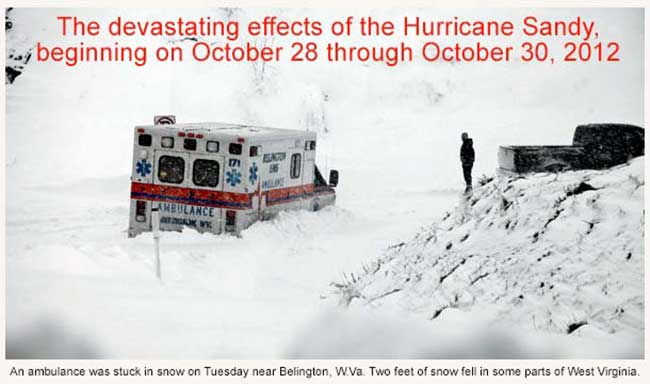

SCRANTON, Pa. — The reach of the storm called Sandy was staggering, with devastation along the coasts, snow in Appalachia, power failures in Maine and high winds at the Great Lakes.

In West Virginia, two feet of snow fell in Terra Alta, where Carrie Luckel said she had to take drastic measures to stay warm. “We are seriously using a turkey fryer to keep our bedroom warm enough to live and a Coleman stove in our bedroom to heat up cans of soup,” Ms. Luckel said. “Our milk is sitting on the roof.”

Along the shores of Lake Michigan in Chicago, gawkers who had come to see the crash of 20-foot waves were struggling against gusts that the National Weather Service said could reach 60 miles per hour. “It’s hard to even stand there and look,” said Mike Magic, 36.

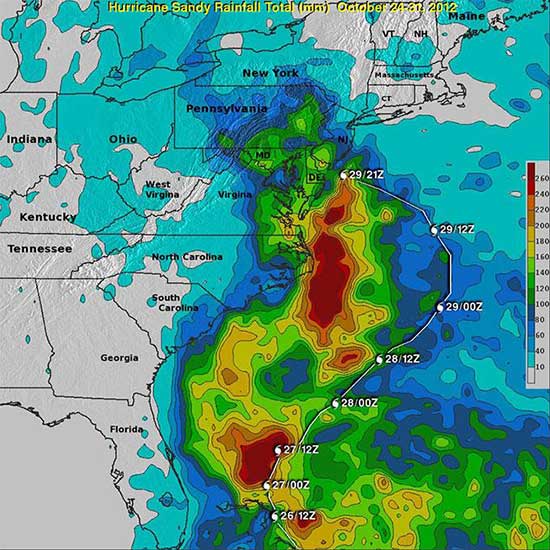

The storm was very unlike last year’s deluging Hurricane Irene, which caused severe flooding across many states. The relative lack of rain and the weakening of the storm as it progresses means that the worst damage — and the historic significance — of this storm will be its battering effect on the East Coast, said Brian McNoldy, a hurricane expert at the University of Miami. “Irene will be remembered only for its rain, and Sandy will be remembered only for its surge,” he said.

While the storm has weakened as it moved inland, its winds downed trees and caused some eight million utility customers to lose power. Coastal flooding hit Rhode Island and Massachusetts, and the storm left local flooding in its wake across Delaware, Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania. In Maryland, the sewage treatment plant for Howard County lost power, and about two million gallons of water and untreated sewage poured into the Patuxent River hourly. Still, Gov. Martin O’Malley said the state was “very, very fortunate to be on the kinder end of this very violent storm.”

Forecasters said on Tuesday that they no longer expected the storm to turn to the northeast and travel across New England. Instead, the track shifted well to the west, and prediction models suggested a path through central Pennsylvania and western New York State before entering southern Ontario by Wednesday, said Eric Blake, a hurricane specialist with the National Hurricane Center in Miami.

In Scranton, residents enjoyed the relief that comes whenever bullets have been dodged.

“People around here are very concerned about flooding after Irene last year — many people are just recovering,” said Simon Hewson, the general manager at Kildare’s Irish Pub. He prepared the establishment for a severe storm, then “just hunkered down and waited,” said Mr. Hewson, who hails from Dublin. He came in the next morning to an undamaged pub: “We got lucky.”

Experience with natural disaster in an environment that climate change has made increasingly unpredictable has taught strong lessons to many of those who have to deal with storms. Amy Shuler Goodwin, director of communications for the office of Gov. Earl Ray Tomblin of West Virginia, said “without question we are better prepared this time around than last time,” referring to the freakishly powerful “derecho” line of storms that slammed across 700 miles of the Midwest and the mid-Atlantic in July.

As the storm continues to move inland and loses contact with the ocean — its source of moisture — rain levels are expected to diminish, though wind damage is still likely.

When it comes time to assess the damage and help clean up the mess caused by the storm, the Army Corps of Engineers will have plenty of work on its hands, said Col. Kent D. Savre, the commander and division engineer for the corps’ North Atlantic division, whose operations stretch from Virginia to Maine; he expects help from corps districts across the nation: “They kind of come to the sound of the guns when there’s an event like this.”

For some, the storm brought wonder. At LeConte Lodge in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, a hike-in set of cabins at 6,600 feet, about 25 visitors huddled around a fire while snow piled up in drifts of up to five feet, said Allyson Virden, who runs the lodge. The 22-inch snowfall is already eleven times greater than the average for October, but Ms. Virden tried looking on the bright side. “We don’t have power to lose up here,” she said. “And it’s gorgeous.”

Reporting was contributed by Brian Stelter from Delaware, Theo Emery from Maryland, John H. Cushman Jr. from Washington, Timothy Williams from New York, Katharine Q. Seelye from Boston, Kim Severson from Atlanta, Steven Yaccino from Chicago and Cynthia McCloud from Terra Alta, W.Va.