Samuel Insull: A Small Man From Nowhere

July 31, 2012

For nineteen months the fugitive had been on the run. He had sailed to Europe after the collapse of his vast business empire, sick of getting hate mail and being hounded by newspaper reporters. In Paris he learned that he was a wanted man in the United States. Eventually he was hauled back to the States and thrown into a New Jersey prison cell. Lying on his cot that night, surrounded by hardened criminals, Samuel Insull—the man who brought electricity to millions of people for the first time—must have looked back at his life and wondered where he had gone wrong.

Insull was born in London England in 1860, the son of a Cockney lay preacher. While he was still in his teens he took a job as the operator of a telephone exchange. His hard work and organizational ability brought him to attention of the boss, Thomas Edison, who soon summoned him to New York to be his private secretary. The great inventor claimed that Insull was the first man he had ever met who worked even harder than he did. He was so impressed that he gave his young assistant sole responsibility for establishing a new subsidiary called Edison Machine Works.

Insull was born in London England in 1860, the son of a Cockney lay preacher. While he was still in his teens he took a job as the operator of a telephone exchange. His hard work and organizational ability brought him to attention of the boss, Thomas Edison, who soon summoned him to New York to be his private secretary. The great inventor claimed that Insull was the first man he had ever met who worked even harder than he did. He was so impressed that he gave his young assistant sole responsibility for establishing a new subsidiary called Edison Machine Works.

Insull knew little about manufacturing, but he was a quick study. Within five years the company had grown from 200 workers to 6000, and was making a 30% return on investment. After a decade in Edison’s employ, Insull was appointed a senior vice president of the newly merged colossus called the General Electric Company.

That was why Samuel Insull loved America: a small man could come from nowhere and achieve great things.

In 1892 Insull decided to break out on his own. He accepted an offer, at one third of his former salary, to become the president of a small, independent electrical generating company in Chicago. He now believed that his greatest opportunity lay not in manufacturing electrical devices, but in creating the power they required.

Edison had staked his fortune on direct current, claiming that Nicola Tesla’s alternating current A.C. electricity was too dangerous. Unfortunately D.C. electricity could not be sent over long distances, and required small power stations to be built on nearly every city block. Because of the D.C. problem it was only feasible to supply electricity to large businesses and affluent homeowners.

But Insull wanted to empower all of the people and provide electricity for the whole city, the suburbs and even rural areas. Rejecting his old mentor’s prejudice against A.C. Insull took a chance on a newly discovered energy technology and ordered manufacturing of new rotary converters based on Nicola Tesla’s alternating current A.C. invention allowing A.C. to be transmitted over long distances and turned back on D.C. for local power use [1].

Then Insull made the single most important innovation in the energy field. He abandoned Edison’s flat rate model of billing for a two-tier system, and sought out customers who needed his electricity during low-use hours. His steam generators could now run at full blast. This allowed him to slash rates for households that put little demand on the system. Thousands of new customers signed up, most of whom had never had access to electricity before.

When Insull first arrived in Chicago there were 25 power companies, which meant that none could maximize its output. To deliver power more efficiently—and to lower prices even more—Insull started buying up his competitors. Within a few years his company had merged with 39 other utilities, expanding all over the region. To organize such a huge power system, Insull created a holding company—a company that owns a large enough portion of another company’s stock to be able to direct its policies [2].

Middle West Utilities was soon supplying one eighth of the power requirements of the whole country. All the new products coming on the market that required electricity, like electric irons, refrigerators and radios, further spurred the growth of Insull’s business [3].

Samuel Insull was now a very rich man. Like Henry Ford, he was also a generous boss. He paid his employees more for a 46 hour work week than they could get for a 60-70 hour week elsewhere. In his spare time he was a leading patron of the arts in Chicago, and worked tirelessly for the war effort. By the twenties Insull had become a hero to the man on the street.

But he had picked up some powerful enemies. The notoriously corrupt Chicago politicians were angry because he refused to pay them bribes. The Wall Street banks resented him because he preferred to deal with banks in London or to sell local bonds to raise funds. The members of the influential Progressive Party hated anyone with money on principle. They rubbed their hands in glee when Insull ran into trouble in the Great Depression, and would do anything they could to hasten his downfall [4].

After the stock market crash in 1929 Insull assumed that the country would soon recover, as most people did, and kept expanding his business. Unfortunately every time the market dropped the banks owned more of his empire. He was advised to sell his stock short, which would have given him an easy way out of his problem. He refused. “We’ve got a responsibility to our stockholders,” he said at the time. “We can’t let them down.”

The London banks ran out of money, and Insull had no choice but to ask Wall Street for a loan to prop up his ailing enterprises. They refused, forcing his holding company into receivership. Within a single day he had to quit more than 60 presidencies and directorships. Thousands of stockholders lost money when his business sank, and Insull went down with the ship.

Once perceived as the most powerful businessman in America, Samuel Insull became the perfect scapegoat for the country’s economic woes. The press took delight in kicking him when he was down. President Roosevelt attacked him in a speech. Illinois prosecutor John Swanson, facing a tough election, announced an investigation of Insull’s activities. “You know, Sam Insull is the greatest man I have ever known,” Swanson admitted in private. “No one has ever done more for Chicago and I know he has never taken a dishonest dollar. . . but Insull knows politics and he will understand . . . I’ve got to do it.”

While Insull was in Europe he was indicted for embezzlement and for using the U.S. mail to defraud the public by selling securities for more than they were worth. He refused to give himself up, convinced that politicians were only trying to cash in on his misfortunes. He fled to Turkey, a country that had no extradition treaty with the U.S., assuming he’d be safe. He was wrong. At the request of the American ambassador he was kidnapped by Turkish agents and shipped back home.

Almost overnight Insull had gone from being a hero to a villain. Locked up in a New Jersey jail cell, he must have searched in vain for an explanation. He was a small man who had come from nowhere and improved millions of people’s lives. Why did they want to cut him down to size?

The trial began on October 2, 1934. In his opening statement the prosecutor accused Insull of dishonest bookkeeping and making a fortune at the expense of “the little people” who had lost their life savings. The press, politicians and most of the general public were salivating, smelling blood.

A series of experts was called to the stand. One after another they testified that Insull had not cooked the books, but had employed exactly the same kind of accounting methods that the government used. He had not taken advantage of his investors, but in fact he had poured most of his fortune into his empire trying to shore it up. The prosecutor pointed to Insull’s income tax returns, in which he had claimed a half a million dollars a year in salary. The defense attorney used the same returns to show that Insull had given away more than that amount to charity [5].

Finally Insull took the hot seat. As he quietly told his story, something unexpected occurred: the people in the courtroom became fascinated by his rags-to-riches tale. The prosecutor tried to object, noticing what was happening. The judge overruled him; he wanted to hear the story, too. Eventually the prosecutor just sat back and listened, as curious as everyone else about Insull’s remarkable life.

When the jury retired, it took them five minutes to reach a verdict. Insull was cleared of all charges [6].

The courts may have found him innocent, but the press thought Insull was guilty by definition: he was a symbol of out-of-control capitalism and therefore responsible for the mess in the country.

Today many respected economists and historians have discovered factual evidence that traces the cause of the Depression to actions of the criminal elites who own the Federal Reserve and the deliberate actions of their goons causing U.S. government interventions in the economy and rigged the system to steal all there was for themselves. The evidence were exposed and presented recently by Thrive documentary film as well. Some things never change, until and unless we, the people change them [7].

Insull fled to Europe, a broken man. “I owe America nothing,” he said. “She did only one thing for me. She gave me the opportunity. I did the rest and I repaid America many times for what she gave me.”

A few years later Insull dropped dead of a heart attack in a Paris subway station. Before his corpse was identified, it was robbed. The press, assuming that Insull was flat broke, played up the angle of a rich man getting his comeuppance.

Once upon a time people were inspired by tales of boys who made good. These days, it seems, rags-to-riches stories have gone out of fashion.

[1] Insull took another risk when he installed massive new turbine generators, which his old friends at General Electric warned him were not feasible. “G.E. engineers can prove anything impossible,” he joked.

[2] By the late twenties Insull was operating one of the first “super-holding companies”, in which sub-holding companies and subsidiaries were stacked on top of each other like a pyramid, allowing him to retain control of 225 separate businesses.

[3] Insull was the first utility operator to realize the importance of marketing. Inspired by P.T. Barnum, he promoted not only electricity but the lifestyle it made possible. His marketing campaign included setting up a chain of shops and publishing a magazine, Electric City, that glamorized household products that ran on electricity.

[4] Insull’s downfall began when businessman Cyrus S. Eaton attempted a hostile takeover. Having to raise a big chunk of money in a hurry to fend off the raid, Insull was forced to turn to the Wall Street banks he had previously spurned.

[5] At the beginning of the Depression, Insull donated 100 million dollars to the city of Chicago to pay for teachers, policemen and firefighters.

[6] One juror, a former sheriff, later explained: “I’ve never heard of a bunch of crooks who thought up a scheme, wrote it all down, and kept an honest and careful record of everything they did.”

[7] We all must beware of the work of the following top crime families, responsible for all evils befalling on all people, all over the world, collectively orchestrating and funding wars, murder and mayhem, through their central banks, nation-less corporations and other institutions, deliberately causing millions upon millions of deaths and unimaginable destruction all over the world, to rule and control planet Earth, exposed by Thrive documentary film. -- The evil bastards are as follows: Rothschild(s), Morgan(s), Rockefeller(s), Carnegie(s), Schiff(s), Herminie(s) and Warburg(s), for centuries these criminal families have been instigating and funding wars, murder, countless fake revolutions, creating and funding terrorist organizations through their secret societies, rewriting the true history as fiction to only benefit themselves and their racketeering businesses at all costs.

Voice-Activated Technology Is Called Safety Risk for Drivers

- By MATT RICHTEL and BILL VLASIC - The New York Times - June 12, 2013

As concerns have intensified about driver distraction from electronic gadgets, automakers have increasingly introduced voice-activated systems that allow drivers to keep their hands on the wheel and eyes on the road. But a new study says that the most advanced of these systems actually create a different, and worse, safety risk, by taking a driver’s mind, if not eyes, off the road.

These systems let drivers use voice commands to dictate a text, send an e-mail and even update a Facebook page. Automakers say the systems not only address safety concerns, but also cater to consumers who increasingly want to stay connected on the Internet while driving.

“What we really have on our hands is a looming public safety crisis with the proliferation of these vehicles,” said Yolanda Cade, a spokeswoman for AAA, whose Foundation for Highway Safety released the study on Wednesday. She characterized the rush to equip cars with Internet-enabled systems as “an arms race.”

The study is among the most exhaustive look to date at the new in-car technology and sets up a potential clash between safety advocates and the auto industry, given that automakers increasingly see profit potential in the new systems.

In some high-end luxury cars, like the BMW 7-series sedan, drivers can dictate e-mails or text messages. And some mainstream models are equipped with options that can translate voice messages into text. The Chevrolet Sonic compact car, for example, has a system that allows drivers to compose texts verbally on an iPhone connected in the vehicle.

More than half of all new cars will integrate some type of voice recognition by 2019, according to the electronics consulting firm IMS Research. The auto companies argue that these systems are safer because they are hands-free.

“We are concerned about any study that suggests that hand-held phones are comparably risky to the hands-free systems we are putting in our vehicles,” said Gloria Bergquist, the vice president for public affairs at the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers in Washington, adding that carmakers are trying to keep consumers connected without them having to use their hand-held phones while driving.

“It is a connected society, and people want to be connected in their car just as they are in their home or wherever they may be,” she said.

In April, the federal government recommended that automakers voluntarily limit the technology in their cars to keep drivers focused. The federal agency that made the recommendation, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, said it would review the latest research .

What makes the use of these speech-to-text systems so risky is that they create a significant cognitive distraction, the researchers found. The brain is so taxed interacting with the system that, even with hands on the wheel and eyes on the road, the driver’s reaction time and ability to process what is happening on the road are impaired.

The research was led by David Strayer, a neuroscientist at the University of Utah who for two decades has applied the principles of attention science to driver behavior. His research has showed, for example, that talking on a phone while driving creates the same level of crash risk as someone with a 0.08 blood-alcohol level, the legal level for intoxication across the country.

In this latest study, he and a team of researchers compared the impact on drivers of different activities, including listening to a book on tape or the radio, and talking on a hand-held phone or hands-free phone.

The researchers compared how the subjects performed when they were not driving with two other conditions: when using a driver simulator and in a car equipped with tools aimed at measuring how well they drove. The researchers used eye-scanning technology to see where driver attention was focused and also measured the electrical activity in the brain.

Mr. Strayer said the results were consistent across all the tests in finding that speech-to-text technology caused a higher level of cognitive distraction than any of the other activities. The research showed, for instance, that the person interacting with speech to text was less likely than in other activities to scan a crosswalk for pedestrians. And that driver showed lowered activity in networks of the brain associated with driving, indicating that those networks were impaired by the interaction with the technology.

Mr. Strayer said that the reason for the heavy load created by the technology was not totally clear. One reason appears to be the amount of effort required to talk to the dashboard, which is greater than talking to a person, who can interrupt and ask for clarification.

With a passenger or even on a phone, the other person says “wait, wait, I didn’t understand,” Mr. Strayer said. “That stuff is gone when you’re trying to compose an e-mail. You have to get your thought in order and lay it out in order.”

Mr. Strayer said the research should give automakers pause. “Look at new cars; they’re enabling sending e-mails, sending text, tweeting, updating Facebook, making movie or dinner reservations with voice commands,” he said. “The assumption is if you’re doing those things with speech-based technology, they’ll be safe. But they’re not.”

But the automakers are not likely to slow down development of the technology unless the law forbids it, said Ronald Montoya, consumer advice editor for Edmunds.com, a research firm.

“They’re not going to pause based on this research,” he said.

When JFK Presidential Words Led to Swift Action

- By ADAM CLYMER - June 8, 2013 - The New York Times

WASHINGTON — These days it is hard to imagine a single presidential speech changing history.

But two speeches, given back to back by President John F. Kennedy 50 years ago this week, are now viewed as critical turning points on the transcendent issues of the last century.

But two speeches, given back to back by President John F. Kennedy 50 years ago this week, are now viewed as critical turning points on the transcendent issues of the last century.

The speeches, which came on consecutive days, took political risks. They sought to shift the nation’s thinking on the “inevitability” of war with the Soviet Union and to make urgent the “moral crisis” of civil rights. Beyond their considerable impact on American minds, these two speeches had something in common that oratory now often misses. They both led quickly and directly to important changes.

On Monday, June 10, 1963, Kennedy announced new talks to try to curb nuclear tests, signaling a decrease in tension between the United States and the Soviet Union. Speaking at American University’s morning commencement, he urged new approaches to the cold war, saying, “And if we cannot end now our differences, at least we can help make the world safe for diversity.”

“In the final analysis,” he continued, “our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future. And we are all mortal.”

The next evening, Kennedy gave an address on national television, sketching out a strong civil rights bill he promised to send to Congress. For the first time, a president made a moral case against segregation. He had previously argued publicly for obedience to court orders and had condemned violence, but not the underlying system.

“We are confronted primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the Scriptures and is as clear as the American Constitution,” Kennedy said. “The heart of the question is whether all Americans are to be afforded equal rights and equal opportunities, whether we are going to treat our fellow Americans as we want to be treated.”

Action followed. An agreement to establish a hot line between Washington and Moscow came in a few days, and a limited nuclear test ban treaty in four months. In just over a year, the 1964 Civil Rights Act became the most important American law of the 20th century. Kennedy, of course, did not live to see the comprehensive civil rights legislation, a crowning achievement of his successor, President Lyndon B. Johnson and Republican leaders like Representative William M. McCulloch of Ohio and Senator Everett M. Dirksen of Illinois.

Robert Dallek, Kennedy’s leading biographer, said the two speeches were “not just two of his best speeches, but two of the better presidential speeches of the 20th century.”

Kathleen Hall Jamieson, the director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania and a scholar of political discourse, said the two “compelling” speeches invited the country “to see the world differently, expanding our concept of basic rights and propelling action vindicated by history.”

They are underappreciated as oratory, she said, because neither had a “simple central phrase” like “Ich bin ein Berliner,” which Kennedy said later that month, or “Ask not what your country can do for you,” from his inaugural address.

Though Theodore C. Sorensen, the president’s main speechwriter, was the principal writer of both speeches, they were prepared in very different ways.

The American University speech was a month in the making, growing out of Kennedy’s sense that if some progress on controlling arms was to be made, it had to happen in 1963, not in the election year of 1964, and from signals from the Kremlin that new talks might be productive. But it was kept secret from the Pentagon, because of fears that generals might object to any steps toward conciliation.

In contrast, the civil rights speech was written in a few hours and was almost not given.

Mr. Dallek said the American University speech reflected Kennedy’s “real passion” about his presidency, the goal of building “not merely peace in our time but peace for all time,” as Kennedy put it that morning.

To achieve it, Kennedy said, it was necessary to “examine our attitude toward peace itself.”

“Too many of us think it is impossible,” Kennedy said. “Too many think it unreal. But that is a dangerous, defeatist belief. It leads to the conclusion that war is inevitable — that mankind is doomed — that we are gripped by forces we cannot control.

“We need not accept that view. Our problems are man-made — therefore, they can be solved by man.”

Another step was to “re-examine our attitude toward the Soviet Union.”

He said that while it was “sad” to read Soviet propaganda insisting that the United States was planning many wars so it could dominate the world, “it is also a warning — a warning to the American people not to fall into the same trap as the Soviets, not to see only a distorted and desperate view of the other side, not to see conflict as inevitable, accommodation as impossible, and communication as nothing more than an exchange of threats.”

He said Americans should understand that “no government or social system is so evil that its people must be considered as lacking in virtue. As Americans, we find communism profoundly repugnant as a negation of personal freedom and dignity. But we can still hail the Russian people for their many achievements — in science and space, in economic and industrial growth, in culture and in acts of courage.”

Reminding his audience that at least 20 million Soviet citizens died in World War II, Kennedy said, “Among the many traits the peoples of our two countries have in common, none is stronger than our mutual abhorrence of war.”

“Today, should total war ever break out again — no matter how — our two countries would become the primary targets. It is an ironic but accurate fact that the two strongest powers are the two in the most danger of devastation. All we have built, all we have worked for, would be destroyed in the first 24 hours.”

On June 11, Kennedy had planned to speak about civil rights if there was trouble in Tuscaloosa, Ala., where Gov. George C. Wallace had vowed to stand in the way to prevent the integration of the University of Alabama. But Wallace simply made a statement and then stepped aside, and the process went smoothly. The speech seemed unnecessary.

Sorensen, who had labored over the Monday speech, went home, only to be summoned back at midafternoon when the president’s brother Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy persuaded Kennedy to go ahead. Sorensen finished his draft with only minutes to spare, and Kennedy ad-libbed concluding paragraphs.

The president had come to the civil rights issue only “grudgingly,” as Mr. Dallek put it. He thought segregation wrong and the Southerners who defended it “hopeless.” But for more than two years in the White House, he had treated the issue as a distraction from not only foreign policy but also tough domestic issues like a tax cut to spur the economy. Moreover, Mr. Dallek said, Kennedy and his brother thought the issue would cost him the Southern states he won in 1960 and could bring his defeat in 1964.

Still, by late spring in 1963 the spread of civil rights demonstrations, and the brutality used in Birmingham and elsewhere to suppress them, forced his hand. And while he had fitfully used the word “moral” in civil rights statements, he had not made it a cause.

He told the nation: “One hundred years of delay have passed since President Lincoln freed the slaves, yet their heirs, their grandsons, are not fully free. They are not yet freed from the bonds of injustice. They are not yet freed from social and economic oppression. And this nation, for all its hopes and all its boasts, will not be fully free until all its citizens are free.”

Kennedy said: “If an American, because his skin is dark, cannot eat lunch in a restaurant open to the public, if he cannot send his children to the best public school available, if he cannot vote for the public officials who represent him, if, in short, he cannot enjoy the full and free life which all of us want, then who among us would be content to have the color of his skin changed and stand in his place? Who among us would then be content with the counsels of patience and delay?”

He was not addressing just the South, or even just Congress. “It is not enough to pin the blame on others, to say this is a problem of one section of the country or another,” he said.

“A great change is at hand, and our task, our obligation, is to make that revolution, that change, peaceful and constructive for all. Those who do nothing are inviting shame as well as violence. Those who act boldly are recognizing right as well as reality.”

This “moral crisis,” he said, “cannot be met by repressive police action. It cannot be left to increased demonstrations in the streets. It cannot be quieted by token moves or talk. It is a time to act in the Congress, in your state and local legislative body and, above all, in all of our daily lives.”

In between the two speeches, another critical issue arose. At a busy intersection in South Vietnam’s capital, Saigon, a Buddhist monk named Thich Quang Duc set himself on fire. That set off the political developments that led to the ouster and murder of President Ngo Dinh Diem just three weeks before Kennedy’s own assassination.

DEBUNKING THE REAL 9/11 MYTHS:

WHY POPULAR MECHANICS CAN NOT FACE UP TO REALITY

- By Adam Taylor

Editor’s note: This is Part 10 of 10 (see Part 9), the conclusion of an extensive report by 9/11 researcher Adam Taylor that exposes the fallacies and flaws in the arguments made by the writers and editors of Popular Mechanics (PM) in the latest edition of Debunking 9/11 Myths. We encourage you to submit your own reviews of the book at Amazon.com and other places where it is sold. (Quotes from PM are shown in red and with page numbers.)

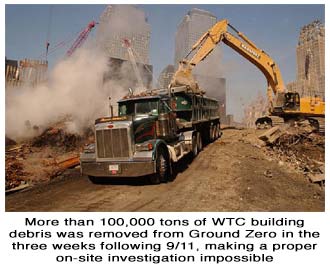

Part 10: Minimal Wreckage to Study

In the last section of their book covering WTC7, PM’s writers and editors discuss the fact that the steel from Ground Zero was quickly removed from the site and recycled. 9/11 researchers have cited this as evidence of a cover-up. However, PM’s writers attempt to explain why there was nothing unusual about this speedy cleanup of Ground Zero, and we see that, once again, their excuses are groundless.

In the last section of their book covering WTC7, PM’s writers and editors discuss the fact that the steel from Ground Zero was quickly removed from the site and recycled. 9/11 researchers have cited this as evidence of a cover-up. However, PM’s writers attempt to explain why there was nothing unusual about this speedy cleanup of Ground Zero, and we see that, once again, their excuses are groundless.

PM starts off by quoting Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) structural engineer Gene Corley:

“There has been some concern expressed by others that the work of the team has been hampered because debris was removed from the site and has subsequently been processed for recycling,” Gene Corley told the U.S. House Representatives’ Committee on Science in March 2002. “This is not the case. The team has had full access to the scrap yards and to the site and has been able to obtain numerous samples. At this point there is no indication that having access to each piece of steel from the World Trade Center would make a significant difference to understanding the performance of the structures.” (p. 86)

Although the FEMA team had some access to the steel and the site, the initial investigation was plagued with problems cited by the Science Committee of the House of Representatives, including:

- The BPAT (Building Performance Assessment Team) did not control the disposition or acquisition of the steel. “The lack of authority of investigators to impound pieces of steel for investigation before they were recycled led to the loss of important pieces of evidence.”

- FEMA required BPAT members to sign confidentiality agreements that “frustrated the efforts of independent researchers to understand the collapse.”

- The BPAT was not granted access to “pertinent building documents.”

- Funding and analysis was severely curtailed. “The BPAT team does not plan, nor does it have sufficient funding, to fully analyze the structural data it collected to determine the reasons for the collapse of the WTC buildings.”

Moreover, Corley complained to the Committee that the Port Authority refused to give his investigators copies of the Towers’ blueprints until he signed a wavier that the blueprints would not be used in a lawsuit against the agency. Corley also admitted that “the delay in the receipt of the plans did somewhat hinder the team’s ability to confirm their understanding of the buildings.”

Contrary to what many believe, the removal of the debris was very rapid, with more than 100,000 tons of it being removed by September 29, 2001. Much of the steel was removed from the site before FEMA had even started its investigation. Although PM apparently sees nothing wrong with how the debris was handled, numerous individuals demanded that the steel be preserved and were upset that the steel was recycled, including professor of fire science Glenn Corbett, fire protection engineer Craig Beyler, and Bill Manning, editor of Fire Engineering Magazine, who deemed the investigation a “half-baked farce…. the destruction and removal of evidence must stop immediately.” Because the steel was recycled so quickly, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) hardly had any steel to examine from the three towers. Much of the steel that NIST did have was left un-catalogued and stored in Hangar 17 at JFK airport. NIST used fallacious reasoning to exclude most of this steel from its primary investigation. Rather than acknowledge the absurdity of this, PM instead notes that NIST relied extensively on computer models to investigate Building 7’s collapse. The writers also quote New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg (whom they also mention has an engineering degree) as saying “Just looking at a piece of metal generally doesn’t tell you anything.” (p. 87)

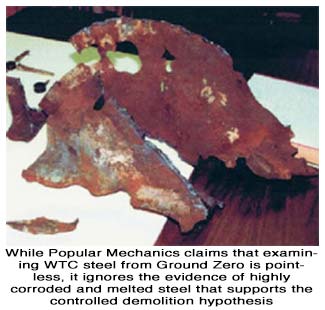

However, examining a piece of metal can actually tell you quite a lot. In fact, one piece of steel from WTC7 was remarkably informative. Two professors from Worcester Polytechnic Institute found that it had been corroded and melted by a liquid eutectic mixture of “primarily iron, oxygen, and sulfur,” which, interestingly enough, are also the primary components of thermite – an incendiary used in military applications to cut through steel like a hot knife through butter. However, this phenomenon was reported nowhere in NIST’s final report on WTC7, even though NIST was obviously aware of it. PM also omits this fact, which is odd, considering that its goal was to “disprove the most prominent conspiracy claims.”

However, examining a piece of metal can actually tell you quite a lot. In fact, one piece of steel from WTC7 was remarkably informative. Two professors from Worcester Polytechnic Institute found that it had been corroded and melted by a liquid eutectic mixture of “primarily iron, oxygen, and sulfur,” which, interestingly enough, are also the primary components of thermite – an incendiary used in military applications to cut through steel like a hot knife through butter. However, this phenomenon was reported nowhere in NIST’s final report on WTC7, even though NIST was obviously aware of it. PM also omits this fact, which is odd, considering that its goal was to “disprove the most prominent conspiracy claims.”

The fact that NIST did not examine and document such pieces of steel from WTC7 casts great doubt on its investigation, as does its own FAQ page: “[We] did not test for the residue of [explosives and thermite] in the steel.” In doing so, NIST has clearly ignored two guidelines in the National Fire Protection Association’s Guide For Fire And Explosion Investigations, NFPA 921. First, NFPA Section 18.15 makes it clear that all fuel sources should be analyzed, including explosives:

“All available fuel sources should be considered and eliminated until one fuel can be identified as meeting all of the physical damage criteria. For example, if the epicenter of the explosion is identified as a 6ft (1.8 m) crater of pulverized concrete in the center of the floor, fugitive natural gas can be eliminated as the fuel, and only fuels that can create seated explosions should be considered. Chemical analysis of debris, soot, soil, or air samples can be helpful in identifying the fuel (emphasis added). With explosives or liquid fuels, gas chromatography, mass spectrography, or other chemical tests of properly collected samples may be able to identify their presence.”

Second, Section 9.3.6 states that physical evidence should not be disposed of until absolutely necessary:

“Once evidence has been removed from the scene, it should be maintained and not be destroyed or altered until others who have a reasonable interest in the matter have been notified. Any destructive testing or destructive examination of the evidence that may be necessary should occur only after all reasonably known parties have been notified in advance and given the opportunity to participate in or observe the testing.”

Furthermore, it’s hard to imagine that there was any justification to remove the WTC7 steel as quickly as the Twin Towers’ steel, given that no one is said to have died in the building, and therefore no victims were to be rescued or found in the WTC7 debris.

It is obvious that the disposal of the steel of Ground Zero was completely unjustifiable, and served only to cover up or obscure the possibility that explosives and incendiaries were used to demolish the Towers and WTC7.

Conclusion

It is apparent that the writers and editors of Popular Mechanics have not sought to learn anything in the past six years since publishing the first edition of their book. When one reads through the updated publication, one immediately finds the same type of dishonest tactics and flimsy arguments found throughout all of their other attacks against the 9/11 Truth movement. Although the writers would like the public to believe that they are merely acting as “investigative journalists,” their latest piece of propaganda shows that this is not even remotely true. If we are to find out what truly happened to the three WTC high-rises on September 11, 2001, then we must continue to research all available data and not limit ourselves to only what self-proclaimed “debunkers” have to say.

See: WTC Probe Ills Bared

Quoted from: NY Times 3/7/2002 - BUILDING STANDARDS - Mismanagement Muddled Collapse Inquiry, House Panel Says

See: telegraph.co.uk - 250 tons of scrap stolen from ruins

See: 911 Truth: Rudy Giuliani & the Feds Destroyed WTC Evidence - YouTube Video

See: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Eus8ShRGgz8#t=7m13s

For a discussion of this, see: How NIST Avoided a Real Analysis of the Physical Evidence of WTC Steel, by Andrea Dreger How NIST Avoided a Real Analysis of the Physical Evidence of WTC Steel

Quoted from: 9-11Research - CLimited Metallurgical Examination, by Jonathan Barnett

NIST mentions this steel from WTC7 and a similarly corroded piece of steel from the Twin Towers, in NCSTAR 1-3C, pp. 229–233. However, NIST performed no analysis of the steel sample from WTC7, and NIST’s conclusion on the sample from the Twin Towers was that it was “unlikely that [the] column experienced degradation prior to the collapse of the towers.” However, NIST’s reasoning for both of these decisions appears fallacy-ridden, as its analysis provided little support for the idea that the samples were corroded post-collapse. (See reference viii by Andrea Dreger, pp. 50–53)

Quoted from: NIST Engineering Laboratory - Questions and Answers about the NIST WTC Towers Investigation

Quoted from: Firefighters for 9-11 Truth - Analyze Fuel Source - NFPA Contradictions

Quoted from: Firefighters for 9-11 Truth - 9.3.6 Spoliation of Evidence - NFPA Contradictions