Fish Off Japan’s Coast Said to Contain Elevated Levels of Cesium

- By HIROKO TABUCHI - The New York Times - October 25, 2012

TOKYO — Elevated levels of cesium still detected in fish off the Fukushima coast of Japan suggest that radioactive particles from last year’s nuclear disaster have accumulated on the seafloor and could contaminate sea life for decades, according to new research.

The findings published in Friday’s issue of the journal Science highlight the challenges facing Japan as it seeks to protect its food supply and rebuild the local fisheries industry.

More than 18 months after the nuclear disaster, Japan bans the sale of 36 species of fish caught off Fukushima, rendering the bulk of its fishing boats idle and denying the region one of its mainstay industries.

Some local fishermen are trying to return to work. Since July, a handful of them have resumed small-scale commercial fishing for species, like octopus, that have cleared government radiation tests. Radiation readings in waters off Fukushima and beyond have returned to near-normal levels.

But about 40 percent of fish caught off Fukushima and tested by the government still have too much cesium to be safe to eat under regulatory limits set by the Japanese government last year, said the article’s author, Ken O. Buesseler, a leading marine chemistry expert at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, who analyzed test results from the 12 months following the March 2011 disaster.

Because cesium tends not to stay very long in the tissues of saltwater fish — and because high radiation levels have been detected most often in bottom-feeding fish — it is likely that fish are being newly contaminated by cesium on the seabed, Mr. Buesseler wrote in the Science article.

“The fact that many fish are just as contaminated today with cesium 134 and cesium 137 as they were more than one year ago implies that cesium is still being released into the food chain,” Mr. Buesseler wrote. This kind of cesium has a half-life of 30 years, meaning that it falls off by half in radioactive intensity every 30 years. Given that, he said, “sediments would remain contaminated for decades to come.”

Officials at Japan’s Fisheries Agency, which conducted the tests, said Mr. Buesseler’s analysis made sense.

“In the early days of the disaster, as the fallout hit the ocean, we saw high levels of radiation from fish near the surface,” said Koichi Tahara, assistant director of the agency’s resources and research division. “But now it would be reasonable to assume that radioactive substances are settling on the seafloor.”

But that was less of a concern than Mr. Buesseler’s research might suggest, Mr. Tahara said, because the cesium was expected to eventually settle down into the seabed.

Mr. Tahara also stressed that the government would continue its vigorous testing and that fishing bans would remain in place until radiation readings returned to safe levels.

Naohiro Yoshida, an environmental chemistry expert at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, said that while he agreed with much of Mr. Buesseler’s analysis, it was too early to reach a conclusion on how extensive radioactive contamination of Japan’s oceans would be, and how long it would have an impact on marine life in the area.

Further research was needed on ocean currents, sediments and how different species of fish are affected by radioactive contamination, he said.

As much as four-fifths of the radioactive substances released from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant are thought to have entered the sea, either blown offshore or released directly into the ocean from water used to cool the site’s reactors in the wake of the accident.

Sea currents quickly dispersed that radioactivity, and seawater readings off the Fukushima shore returned to near-normal levels. But fish caught in the area continue to show elevated readings for radioactive cesium, which is associated with an increased risk of cancer in humans.

Just two months ago, two greenling caught close to the Fukushima shore were found to contain more than 25,000 becquerels a kilogram of cesium, the highest cesium levels found in fish since the disaster and 250 times the government’s safety limit.

The operator of the Fukushima plant, the Tokyo Electric Power Company, said that the site no longer released contaminated water into the ocean, and that radiation levels in waters around the plant had stabilized.

But Yoshikazu Nagai, a spokesman for the company, said he could not rule out undetected leaks into the ocean from its reactors, the basements of which remain flooded with cooling water.

To reduce the chance of water from seeping out of the plant, Tokyo Electric is building a 2,400-foot-long wall between the site’s reactors and the ocean. But Mr. Nagai said the steel-and-concrete wall, which will reach 100 feet underground, would take until mid-2014 to build.

DANGER, DO NOT COMPLY!

This is the picture of the complete social Mind-Body control, turning people into numbed and constantly monitored and tracked costumers. - The ultimate goal and dream of the criminal Nation-Less Corporations.

In Mobile World, Tech Giants Scramble to Get Up to Speed

- By CLAIRE CAIN MILLER SOMINI SENGUPTA - The New York Times - October 22, 2012

SAN FRANCISCO — Intel made its fortune on the chips that power personal computers, and Microsoft on the software that goes inside. Google’s secret sauce is that it finds what you are looking for on the Internet. But the ground is shifting beneath these tech titans because of a major force: the rise of mobile devices.

These and other tech companies are scrambling to reinvent their business models now that the old model — a stationary customer sitting at a stationary desk — no longer applies. These companies once disrupted traditional businesses, from selling books and music to booking hotels. Now they are being upended by the widespread adoption of smartphones and tablets.

These and other tech companies are scrambling to reinvent their business models now that the old model — a stationary customer sitting at a stationary desk — no longer applies. These companies once disrupted traditional businesses, from selling books and music to booking hotels. Now they are being upended by the widespread adoption of smartphones and tablets.

“Companies are having to retool their thinking, saying, ‘What is it that our customers are doing through the mobile channel that is quite distinct from what we are delivering them through our traditional Web channel?’ ” said Charles S. Golvin, an analyst at Forrester Research, the technology research firm.

He added, “It’s hilarious to talk about traditional Web business like it’s been going on for centuries, but it’s last century.”

The industry giants remain highly profitable drivers of the economy. Yet the world’s shift to computing on mobile devices is taking a toll, including disappointing earnings reports last week from Google, Microsoft and Intel, in large measure related to revenue from mobile devices. Investors are in suspense over Facebook’s earnings to be disclosed Tuesday, for much the same reason. Yahoo’s new chief, Marissa Mayer, said on Monday that Yahoo had failed to capitalize on mobile and must become a predominantly mobile company.

Demand for Intel chips inside computers — which are much more profitable than those inside smartphones — is plummeting. At Microsoft, sales of software for PCs are sharply declining. At Google, the price that advertisers pay when people click on ads has fallen for a year. This is partly because, while mobile ads are exploding, they cost less than Internet ads; advertisers are still figuring out how to make them most effective.

Since its initial public offering, Facebook has lost half its value on Wall Street under pressure to make more money from mobile devices, now that six of 10 Facebook users log in on their phones.

Making money will now depend on how deftly tech companies can track their users from their desktop computers to the phones in their palms and ultimately to the stores, cinemas and pizzerias where they spend their money. It will also depend on how consumers — and government regulators — will react to having every move monitored.

Facebook is already experimenting with ways to use what it knows about its users to show ads when they are using other mobile apps. Google can link what a logged-in user does on the computer and phone, to show someone a cellphone ad based on what they have searched for on a computer at home, for instance. But just last week, European regulators warned Google to amend its privacy policy that allows it to gather information about people across diverse Google products, from Gmail to YouTube.

In addition, Nielsen found that only one in five smartphone users described ads on phones as “acceptable.”

Today almost half of Americans own a smartphone, according to comScore — an astoundingly fast adoption since Apple introduced the iPhone just five years ago. The amount of time people spend on their phones surfing the Web, using apps, playing games and listening to music has more than doubled in the last two years, to 82 minutes a day, according to eMarketer; the time spent online on computers will grow just 3.6 percent this year.

“What has caught people off guard has been acceleration of the multitude of things that you can do with a smartphone,” said David B. Yoffie, a Harvard Business School professor who studies the technology sector.

“The Web started in 1993, ’94,” he added. “It didn’t disrupt everything for a decade and a half. The smartphone revolution started a half decade ago. Because of the existence of the Web, it allowed the phone to have a disruptive impact in a shorter time frame.”

Still, mobile provides huge opportunities for these businesses, industry analysts say. That is largely because people reveal much more about themselves on phones than they do on computers, from where they go and when they sleep to whom they talk to and what they want to buy.

Consumers may be put off by the intrusion of marketers into their daily lives, but companies say the trade-off can be worth it — an unprompted calendar alert, say, that tells you whether you’ll be late for a meeting or a coupon when you are near a shop.

“We’re really starting to live in a new reality, one where the ubiquity of screens really helps users move from intent to action much faster and more seamlessly,” Larry Page, Google’s chief executive, told analysts last week. “It will create new opportunity in advertising.”

Companies are addressing the challenges in different ways. Despite the disappointment in its recent earnings report, Google says it is on track to earn $8 billion from mobile ads, apps and media in the coming year, and has activated half a billion devices running its mobile operating system, Android. Google earns the majority of mobile ad dollars.

It is offering location-based ads, like a T-Mobile campaign that sent users ads when they were near stores. Some mobile ads already make more money than desktop ads, said Google’s chief financial officer, Patrick Pichette.

But one of Google’s biggest challenges is tracking whether people make a purchase after they see a mobile ad. Unlike online, where Google knows if someone buys a camera after searching for it, the company does not know if someone searches for a Thai restaurant nearby and then eats there. That is why it is trying to follow people into the physical world, with services like Wallet for payments and Offers for coupons. Facebook is trying to use what it knows about its billion users to serve up ads on other applications they download on their phones. For instance, a soda brand that wants to target men in Los Angeles who like the Lakers could show them ads not only when they are logged into Facebook’s mobile app, but on other apps as well.

“We think that showing mobile ads outside of Facebook is another great way for people to see relevant ads and discover new apps,” the company said in response to an e-mail inquiry.

Not wanting to watch from the sidelines as people abandon computers for smartphones, Microsoft on Friday is introducing a version of its Windows software tailored for touch-screen devices and a new tablet, the Surface.

But Microsoft executives told analysts last week that the slowdown in computer technology was because of other factors besides mobile, like tough economic conditions and companies waiting to buy software until its new software, Windows 8, arrived.

Microsoft’s chief executive, Steven A. Ballmer, called Windows 8 “the beginning of a new era at Microsoft.”

Intel is playing catch-up by making chips for more than two dozen smartphones and tablets coming to market. The shift to mobile has also created a new market for Intel: Its chips are in the huge servers that power the cloud, where much mobile data is stored.

“As the market for smartphones and tablets evolved, the company historically didn’t have a presence,” said Jon Carvill, an Intel spokesman. “This year, that’s started to change.”

For other tech companies, mobile has been a boon from early on. Apple became the most valuable company in the United States selling the iPhone and iPad. Recently, Apple built its own mobile maps to replace Google’s maps on the iPhone in part because it wanted to keep valuable information about users’ location searches to itself and away from its competitor.

Nvidia and Qualcomm are making processors for mobile devices. Amazon and eBay are selling people things even on small screens. And mobile phone owners have found some services — like Zillow for real estate, Yelp for local businesses and OpenTable for restaurant reservations — better on phones than on computers, and revenue has followed.

For investors and others trying to solve the riddle of making money on mobile users, Marc Andreessen, the venture capitalist, extolled the virtues of the mobile era this way: “We’re going to know a tremendous amount about people.”

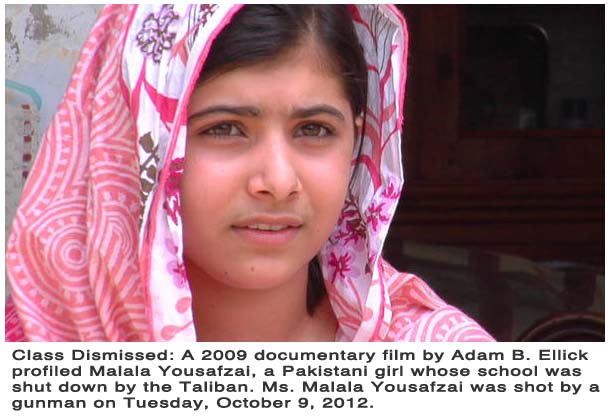

Taliban Gun Down Malala Yousafzai, the Girl Who Spoke Up for Her Rights

- By DECLAN WALSH - The New York Times - October 9, 2012

KARACHI, Pakistan - At the age of 11, Malala Yousafzai took on the Taliban by giving voice to her dreams. As turbaned fighters swept through her town in northwestern Pakistan in 2009, the tiny schoolgirl spoke out about her passion for education — she wanted to become a doctor, she said — and became a symbol of defiance against Taliban subjugation.

On Tuesday, cowered, masked Taliban gunmen answered Ms. Yousafzai’s courage with bullets, singling out the 14-year-old on a bus filled with terrified schoolchildren, then shooting her in the head and neck. Two other girls were also wounded in the attack. All three survived, but late on Tuesday doctors said that Ms. Yousafzai was in critical condition at a hospital in Peshawar, with a bullet possibly lodged close to her brain.

A Taliban spokesman, Ehsanullah Ehsan, confirmed by phone that Ms. Yousafzai had been the target, calling her crusade for education rights an “obscenity.”

“She has become a symbol of Western culture in the area; she was openly propagating it,” Mr. Ehsan said, adding that if she survived, the militants would certainly try to kill her again. “Let this be a lesson.”

The Taliban’s ability to attack Pakistan’s major cities has waned in the past year. But in rural areas along the Afghan border, the militants have intensified their campaign to silence critics and impose their will.

That Ms. Yousafzai’s voice could be deemed a threat to the Taliban — that they could see a schoolgirl’s death as desirable and justifiable — was seen as evidence of both the militants’ brutality and her courage.

“She symbolizes the brave girls of Swat,” said Samar Minallah, a documentary filmmaker who has worked among Pashtun women. “She knew her voice was important, so she spoke up for the rights of children. Even adults didn’t have a vision like hers.”

Ms. Yousafzai came to public attention in 2009 as the Pakistani Taliban swept through Swat, a picturesque valley once famed for its music and tolerance and as a honeymoon destination.

Her father ran one of the last schools to defy Taliban orders to end female education. As an 11-year-old, Malala — named after a mythic female figure in Pashtun culture — wrote an anonymous blog documenting her experiences for the BBC. Later, she was the focus of documentaries by The New York Times and other media outlets.

“I had a terrible dream yesterday with military helicopters and the Taliban,” she wrote in one post titled “I Am Afraid.”

The school was eventually forced to close, and Ms. Yousafzai was forced to flee to Abbottabad, the town where Osama bin Laden was killed last year. Months later, in summer 2009, the Pakistani Army launched a sweeping operation against the Taliban that uprooted an estimated 1.2 million Swat residents.

The Taliban were sent packing, or so it seemed, as fighters and their commanders fled into neighboring districts or Afghanistan. An uneasy peace, enforced by a large military presence, settled over the valley.

Ms. Yousafzai grew in prominence, becoming a powerful voice for the rights of children. In 2011, she was nominated for the International Children’s Peace Prize. Later, Yousaf Raza Gilani, the prime minister at the time, awarded her Pakistan’s first National Youth Peace Prize.

Mature beyond her years, she recently changed her career aspiration to politics, friends said. In recent months, she led a delegation of children’s rights activists, sponsored by Unicef, that made presentations to provincial politicians in Peshawar.

“We found her to be very bold, and it inspired every one of us,” said another student in the group, Fatima Aziz, 15.

Ms. Minallah, the documentary maker, said, “She had this vision, big dreams, that she was going to come into politics and bring about change.”

That such a figure of wide-eyed optimism and courage could be silenced by Taliban violence was a fresh blow for Pakistan’s beleaguered progressives, who seethed with frustration and anger on Tuesday. “Come on, brothers, be REAL MEN. Kill a school girl,” one media commentator, Nadeem F. Paracha, said in an acerbic Twitter post.

In Parliament, Prime Minister Raja Pervez Ashraf urged his countrymen to battle the mind-set behind such attacks. “She is our daughter,” he said.

The attack was also a blow for the powerful military, which has long held out its Swat offensive as an example of its ability to conduct successful counterinsurgency operations. The army retains a tight grip over much of Swat. But that Tuesday’s shooting could take place in the center of Mingora, the valley’s largest town, offered evidence that the Taliban were creeping back.

“This is not a good sign,” Kamran Khan, the most senior government official in Swat, said by phone. “It’s very worrisome.”

The Swat Taliban are a subgroup of the wider Pakistani Taliban movement based in South Waziristan. Their leader, Maulvi Fazlullah, rose to prominence in 2007 through an FM radio station that espoused Islamist ideology.

After 2009, Maulvi Fazlullah and his senior commanders were pushed across the border into the Afghan provinces of Kunar and Nuristan, where Pakistani officials say they are still being sheltered — a source of growing tension between the Pakistani and Afghan governments.

But over the last year or so, small groups of Taliban guerrillas have slowly filtered back into Swat, where they have mounted hit-and-run attacks on community leaders deemed to have collaborated with the government.

On Aug. 3, a Taliban gunman shot and wounded Zahid Khan, the president of the local hoteliers association and a senior community leader, in Mingora. It was the third such attack in recent months, a senior official said.

The military has asserted control in Swat through a large military presence in the valleys and support for private tribal militias tasked with keeping the Taliban at bay. But soldiers have also been accused of human rights abuses, particularly after a leaked videotape in 2010 showed uniformed men apparently massacring Taliban prisoners.

In response to criticism, the army chief, Gen. Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, announced an inquiry into the shootings. An army spokesman said it was not yet complete.

Shah Rasool, the police chief in Swat, said that all roads leading out of Mingora had been barricaded and that more than 30 militant suspects had been detained.

Reporting was contributed by Sana ul Haq from Mingora, Pakistan; Ismail Khan from Peshawar, Pakistan; Ihsanullah Tipu Mehsud from Islamabad, Pakistan; and Zia ur-Rehman from Karachi.

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: October 9, 2012

An earlier version of the caption with the picture atop this article misidentified the city where Malala Yousafzai was attacked. It is Mingora, not Peshawar.

The 3 barbaric, Abrahamic, Adam and Eve based, misogynist, man-made, patriarchal religions: Judaism and its 2 derivatives: Christianity and Islam are, and have always been the agents and promoter of ignorance, hate, violence, rape, murder, plunder, mediocrity and stupidity.

Brave Malala Yousafzai, A Pakistani 12 years old girl, fighting for her freedom and her right to receive education

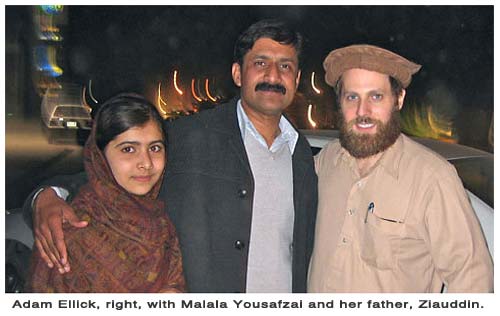

- By ADAM B. ELLICK - October 9, 2012 - The New York Times

I had the privilege of following Malala Yousafzai, on and off, for six months in 2009, documenting some of the most critical days of her life for a two-part documentary. We filmed her final school day before the Taliban closed down her school in Pakistan’s Swat Valley; the summer when war displaced and separated her family; the day she pleaded with President Obama’s special representative to Afghanistan and Pakistan, Richard Holbrooke, to intervene; and the uncertain afternoon she returned to discover the fate of her home, school and her two pet chickens.

A year after my two-part documentary on her family was finished, Malala and her father, Ziauddin, had become my friends. They stayed with me in Islamabad. Malala inherited my old Apple laptop. Once, we went shopping together for English-language books and DVDs. When Malala opted for some trashy American sitcoms, I was forced to remind myself that this girl – who had never shuddered at beheaded corpses, public floggings, and death threats directed at her father — was still just a kid.

Today, she is a teenager, fighting for her life after being gunned down by the Taliban for doing what girls do all over the world: going to school.

The Malala I know transformed with age from an obedient, rather shy 11-year-old into a publicly fearless teenager consumed with taking her activism to new heights. Her father’s personal crusade to restore female education seemed contagious. He is a poet, a school owner and an unflinching educational activist. Ziauddin is truly one of most inspiring and loving people I’ve ever met, and my heart aches for him today. He adores his two sons, but he often referred to Malala as something entirely special. When he sent the boys to bed, Malala was permitted to sit with us as we talked about life and politics deep into the night.

After the film was seen, Malala became even more emboldened. She hosted foreign diplomats in Swat, held news conferences on peace and education, and as a result, won a host of peace awards. Her best work, however, was that she kept going to school.

In the documentary, and on the surface, Malala comes across as a steady, calming force, undeterred by anxiety or risk. She is mature beyond her years. She never displayed a mood swing and never complained about my laborious and redundant interviews.

But don’t be fooled by her gentle demeanor and soft voice. Malala is also fantastically stubborn and feisty — traits that I hope will enable her recovery. When we struggled to secure a dial-up connection for her laptop, her Luddite father scurried over to offer his advice. She didn’t roll an eye or bark back. Instead, she diplomatically told her father that she, not he, was the person to solve the problem — an uncommon act that defies Pakistani familial tradition. As he walked away, she offered me a smirk of confidence.

Another day, Ziauddin forgot Malala’s birthday, and the non-confrontational daughter couldn’t hold it in. She ridiculed her father in a text message and forced him to apologize and to buy everyone a round of ice cream — which always made her really happy.

Her father was a bit traditional, and as a result, I was unable to interact with her mother. I used to chide Ziauddin about these restrictions, especially in front of Malala. Her father would laugh dismissively and joke that Malala should not be listening. Malala beamed as I pressed her father to treat his wife as an equal. Sometimes I felt like her de-facto uncle. I could tell her father the things she couldn’t.

I first met Malala in January 2009, just 10 days before the Taliban planned to close down her girls’ school, and hundreds of others in the Swat Valley. It was too dangerous to travel to Swat, so we met in a dingy guesthouse on the outskirts of Peshawar, the same city where she is today fighting for her life in a military hospital.

In 10 days, her father would lose the family business, and Malala would lose her fifth-grade education. I was there to assess the risks of reporting on this issue. With the help of a Pakistani journalist, I started interviewing Ziauddin. My anxiety rose with each of his answers. Militants controlled the checkpoints. They murdered anyone who dissented, often leaving beheaded corpses on the main square. Swat was too dangerous for a documentary.

I then solicited Malala’s opinion. Irfan Ashraf, a Pakistani journalist who was assisting my reporting and who knew the family, translated the conversation. This went on for about 10 minutes until I noticed, from her body language, that Malala understood my questions in English.

“Do you speak English?” I asked her.

“Yes, of course,” she said in perfect English. “I was just saying there is a fear in my heart that the Taliban are going to close my school.”

I was enamored by Malala’s presence ever since that sentence. But Swat was still too risky. For the first time in my career, I was in the awkward position of trying to convince a source, Ziauddin, that the story was not worth the risk. But Ziauddin fairly argued that he was already a public activist in Swat, prominent in the local press, and that if the Taliban wanted to kill him or his family, they would do so anyway. He said he was willing to die for the cause. But I never asked Malala if she was willing to die as well.

Finally, my favorite memory of Malala is the only time I was with her without her father. It’s the scene at the end of the film, when she is exploring her decrepit classroom, which the military had turned into a bunker after they had pushed the Taliban out of the valley. I asked her to give me a tour of the ruins of the school. The scene seems written or staged. But all I did was press record and this 11-year-old girl spoke eloquently from the heart.

She noticed how the soldiers drilled a lookout hole into the wall of her classroom, scribbling on the wall with a yellow highlighter, “This is Pakistan.”

Malala looked at the marking and said: “Look! This is Pakistan. Taliban destroyed us.”

In her latest e-mail to me, in all caps, she wrote, “I WANT AN ACCESS TO THE WORLD OF KNOWLEDGE.” And she signed it, “YOUR SMALL VIDEO STAR.”

I too wanted her to access the broader world, so during one of my final nights in Pakistan, I took a long midnight walk with her father and spoke to him frankly about options for Malala’s education. I was less concerned with her safety as the Pakistani military had, in large part, won the war against the Taliban. We talked about her potential to thrive on a global level, and I suggested a few steps toward securing scholarships for elite boarding schools in Pakistan, or even in the United States. Her father beamed with pride, but added: “In a few years. She isn’t ready yet.”

I don’t think he was ready to let her go. And who can blame him for that?

The 3 barbaric, Abrahamic, Adam and Eve based, misogynist, man-made, patriarchal religions: Judaism and its 2 derivatives: Christianity and Islam are, and have always been the agents and promoter of ignorance, hate, violence, rape, murder, plunder, mediocrity and stupidity.