Anonymous - Message to the American People

Federal judge blocks National Defense Authorization Act provision

- By Dean Kuipers - Los Angeles Times - May 18, 2012

In a stunning turnaround for an act of Congress, a judge ruled Wednesday that a counterterrorism provision of the National Defense Authorization Act, an annual defense appropriations bill, is unconstitutional. Federal district Judge Katherine B. Forrest issued an injunction against use of the provision on behalf of a group of journalists and activists who had filed suit in March, claiming it would chill free speech.

In her decision published Wednesday, Forrest, in the Southern District of New York, ruled that Section 1021 of NDAA was facially unconstitutional — a rare finding — because of the potential that it could violate the 1st Amendment.

“Plaintiffs have stated a more than plausible claim that the statute inappropriately encroaches on their rights under the First Amendment,” she wrote, addressing the constitutional challenge.

Seven individuals, including Pulitzer Prize-winning former New York Times foreign correspondent Chris Hedges, MIT linguist Noam Chomsky and “Pentagon Papers” activist Daniel Ellsberg, had sued President Barack Obama, Defense Secretary Leon Panetta, and a host of other government officials, stating they were forced to curtail some of their reporting and activist activities for fear of violating Section 1021. That section prohibits providing substantial support for terrorist groups, but gives little definition of what that means. Environmental activists were also poised to join the suit if it expanded.

Judge Forrest also found that the language of Section 1021 was too vague, meaning it was too hard to know when one may or may not be subject to detention.

“It was really unusual for a judge to declare unconstitutional a major provision of an act of Congress. I can’t remember the last time that ever happened,” said Carl Mayer, co-counsel for the plaintiffs. “The judge recognized that, but felt it was necessary to protect our constitution and to protect our democracy. There’s a lot of activists who understand how serious this is, but it’s less well known to the general public.”

The suit demands that Congress cut or reform this section of the law, which allows the U.S. military to indefinitely detain without charges anyone — including U.S. citizens — who may have “substantially supported” terrorists or their “associated forces,” without defining what those terms mean. President Obama signed the bill on Dec 31, 2011, with a signing statement saying that the law was redundant of powers already provided to the government under the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (passed after 9/11), and that these powers would not be used against U.S. citizens. The next administration may decide differently, however.

The plaintiffs made their cases very clear. Hedges had said that he could no longer interview some of his contacts in the Middle East because associating with these individuals might subject him to indefinite detention. Similarly, one of the founders of Occupy London, Kai Wargalla, discovered that the city of London Police Department had categorized her organization as “domestic terrorism/extremism” — among a list of groups that included Al Qaeda. Along with her work supporting Wikileaks, she said she felt primed for a visit from the rendition patrol.

Government attorneys had challenged the issue that any of these people had standing, but Forrest ruled that they did.

“That goes right back to the 1st Amendment issue,” says plaintiff co-counsel Bruce Afran. “Whenever a person is put in fear of exercising their constitutional rights, then they have standing to challenge the statute. All of our plaintiffs said they have changed their journalistic activities in fear of being brought under the statute. Alexa O’Brien [Usdayofrage.org founder and Wikileaks supporter, and suit plaintiff] said she has decided against publishing certain interviews with Guantanamo detainees because she is fearful that that will be deemed 'substantial support' under the law.”

“When you talk about the environmental groups, all the time they’re branded rhetorically as terrorists, but what this law was doing was setting up a situation where they could actually be apprehended as terrorists without the benefit of a trial by jury,” Mayer adds.

The judge’s decision is subject to appeal. Congress can also change the law; an effort to remove the language about indefinite detention was brought up as an amendment by Rep. Adam Smith (D-Wash.) in a bill to modify the NDAA on Thursday, but failed by a 182-238 vote.

RELATED:

Obama signs defense bill but balks at terrorism provisions

Unabomber billboard continues to hurt Heartland Institute

Activist sue Obama, others over National Defense Authorization Act

Foster and Kimberly Gamble, filmmakers of THRIVE, explain how the Thrive Solutions Model helped stop the toxic aerial spray program in California.

How the Sector Model Helped to Stop Toxic Spray Program in California

Mother concerned about FLU Epidemic caused by Chemtrails – Hollywood Does Chemtrails

Mother concerned about FLU epidemic caused by chemtrails – Hollywood Does Chemtrails U.S. Air Force Study Proposed 2009 Influenza Pandemic in 1996: Kurt Nimmo Infowars March 5, 2009 On June 17, 1996, the U.S. Air Force released Air Force 2025, “a study designed to comply with a directive from the chief of staff of the [...]

Tough Flu Season in U.S., Especially for the Elderly

By DONALD G. McNEIL Jr. - The New York Times - January 18, 2013

This year’s flu season is shaping up to be “worse than average and particularly bad for the elderly,” Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, the nation’s top federal disease-control official, said Friday.

This year’s flu season is shaping up to be “worse than average and particularly bad for the elderly,” Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, the nation’s top federal disease-control official, said Friday.

But the season appears to have peaked, added Dr. Frieden, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with new cases declining over most of the nation except for the far West.

Spot shortages of flu vaccine and flu-fighting medicine are occurring, but that reflects uneven distribution, not a supply crisis, federal officials said. They urged people seeking flu shots to consult flu.gov and doctors to check preventinfluenza.org for suppliers.

Vaccine makers will ultimately be able to deliver 145 million doses, 10 million more than projected earlier, the officials said. The Food and Drug Administration has allowed the maker of Tamiflu to release two million doses it had in storage.

The older Tamiflu is perfectly good, said Dr. Margaret A. Hamburg, the commissioner of the F.D.A., who joined Dr. Frieden in a telephone news conference. “It’s not outdated, it just has older labeling,” Dr. Hamburg said. “Repackaging it would take weeks,” she added, so her agency told the company not to bother.

Weekly recorded deaths from flu and pneumonia are still rising, and are well above the “epidemic” curve for the first time. But how severe a season ultimately proves depends on how long high weekly death rates persist. Flu deaths often are not recorded until March or April, well after new infections taper off.

Dr. Frieden said the season appeared to resemble the “moderately severe” season of 2003-4, which also had an early start and was dominated by an H3N2 strain. In such seasons, 90 percent of all deaths occur among those over 65. Flu hospitalization rates are “quite high” now, Dr. Frieden said, and most of those hospitalized are elderly.

Last year’s flu season was unusually mild. At the end of the season last year, 34 children had died.

So far this season, the C.D.C.’s count of pediatric flu deaths, which includes premature infants and teenagers up to age 17 — has risen to 29, although this is acknowledged to be an undercount as it is only of lab-confirmed influenza cases reported to the agency.

Henry L. Niman, a flu-watcher who follows state death registries and news reports, counts about 40 pediatric deaths so far and predicted that the total would ultimately be close to the 153 of the 2003-4 season, but much less than in the 2009-10 “swine flu” pandemic, when 282 children died. That flu was a strain never seen before and many more children caught it. The elderly had surprising resistance to getting it, presumably because similar flus that circulated 40 or more years ago had given them some immunity. But among those elderly people who did catch it, the death rates were high.

Dr. Frieden suggested that the elderly avoid contact with sick children.

“Having a grandparent baby-sit a sick child may not be a good idea,” he said.

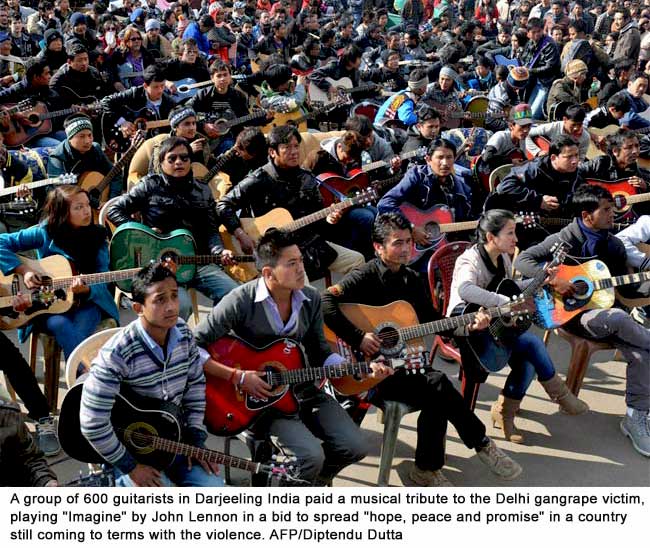

Imagine an India for women: 600 guitarists pay tribute to New Delhi December 16, 2012 gang rape victim

A group of over 600 guitarists have paid a musical tribute to the Delhi gang raped victim, playing "Imagine" by John Lennon in a bid to spread "hope, peace and promise" in a country still coming to terms with the violence.

The group assembled at a music festival in the eastern hilltown of Darjeeling on Thursday, nearly three weeks after the brutal rape and murder of a student on a moving bus in New Delhi brought an outpouring of national anger.

"We chose this song because it talks about hope, peace and promise," said Sonam Bhutia, tourism secretary of Darjeeling and one of the festival organisers.

"The song is so inspiring. It talks about a universe without any boundaries," Bhutia said of the 1971 Lennon track.

"The tribute was a gesture on our part to show that we are with the victim's family in their hour of unimaginable sorrow."

The savage attack on the woman has triggered countrywide protests with calls for better safety and an overhaul of laws governing crimes against women.

New Delhi gang-rape suspects in court amid chaotic scenes

The Telegraph - January 03, 2013

Five men charged with the gang-rape and murder of a student in New Delhi have appeared in court for the first time amid calls for them to be hanged.

The five, who could face the death penalty if convicted, are charged with kidnap, robbery and conspiracy over the attack on December 16 that sparked mass protests in India and soul-searching about levels of violence against women.

The magistrate hearing the case ordered that their first appearance in court take place behind closed doors.

"The court has become jam-packed," magistrate Namrita Aggarwal told the court amid noisy protests from lawyers and a media scrum. "It has become impossible for this court to conduct proceedings in this case."

The hearing comes as four Indian policemen were suspended over the handling of another suspected rape and murder case near Delhi. A 21-year-old woman's body was found on Saturday. The father of the alleged victim, a factory employee in Noida, told the BBC she was gang-raped, and accused the police of initially failing to react when he reported her disappearance. Two have been arrested while a third has fled.

Rowdy protests by some lawyers, who were denouncing other advocates who have stepped forward to defend the accused, delayed the start of proceedings in the packed court room and police were called in to restore order.

Late morning, several blue Delhi Police buses escorted by two police cars were seen driving into the Saket court complex in south New Delhi after jail authorities confirmed the suspects had been sent for their hearing.

The defendants have been named as Ram Singh, Mukesh Singh, Vijay Sharma, Akshay Thakur and Pawan Gupta.

A sixth accused, who is 17, is to be tried in a separate court for juveniles.

It normally takes months for the prosecution to assemble such a case, but the legal proceedings are getting under way barely a week after the 23-year-old student died of her injuries in a Singapore hospital.

The government, sensitive to criticism that a sluggish justice system often compounds the agony of victims, has pledged to fast-track the case against the defendants who are aged between 17 and 35. They all live in Delhi.

Police have pledged "maximum security" during the hearing at the court amid fears for the defendants' safety. A man was arrested last week as he allegedly tried to plant a crude bomb near the home of one of the men.

Legal experts say the magistrate Namrita Aggarwal will likely transfer the case to a higher court during Monday's hearing.

"The court will ask them if they have lawyers and then it will appoint an Amicus Curiae (lawyer) to represent them and supply copies of the charge sheet to the accused," said Vishwender Verma, a senior advocate at Delhi High Court.

"The case will then be committed to a sessions court as a magistrates' court cannot try rape and murder cases."

The student had spent the evening at a cinema with her boyfriend on the night of the attack. After failing to flag down an autorickshaw, they were lured onto a school bus they thought would take them home.

Instead, a gang are alleged to have taken it in turns to rape the young woman as well as sexually assault her with an iron bar that they also used to attack her companion. The pair were then thrown out of the moving vehicle.

Outlining their case before the same court in Saket on Saturday, prosecutors said there was DNA evidence to tie the defendants to the crime scene.

"The blood of the victim tallied with the stains found on the clothes of the accused," said Rajiv Mohan, part of the prosecution team.

There have been widespread calls for the attackers to be hanged, including from the victim's family.

Her father was quoted by Britain's Sunday People newspaper at the weekend as saying he wanted "death for all six of them" as well calling for his daughter's name to be made public "to give courage to other women".

But in an interview with Monday's Hindustan Times he said he only supported his daughter's name being used for a new law covering crimes against women.

"I want my daughter to be known as the one who could bring a change in the society and laws, and not as a victim of a barbaric crime," he told the paper.

Rape cases are usually held behind closed doors in India and it will be up to the court to decide what the media will be allowed to report.

The police have issued an advisory saying "it shall not be lawful for any person to print or publish any matter in relation to such proceedings" unless they receive permission from the court.

Water fluoridation is a peculiarly American phenomenon

Water fluoridation is a peculiarly American phenomenon. It started at a time when Asbestos lined our pipes, lead was added to gasoline, PCBs filled our transformers and DDT was deemed so “safe and effective” that officials felt no qualms spraying kids in school classrooms and seated at picnic tables. One by one all these chemicals have been banned, but fluoridation remains untouched.

Water fluoridation is a peculiarly American phenomenon. It started at a time when Asbestos lined our pipes, lead was added to gasoline, PCBs filled our transformers and DDT was deemed so “safe and effective” that officials felt no qualms spraying kids in school classrooms and seated at picnic tables. One by one all these chemicals have been banned, but fluoridation remains untouched.

For over 50 years US government officials have confidently and enthusiastically claimed that fluoridation is “safe and effective.” However, they are seldom prepared to defend the practice in open public debate. Actually, there are so many arguments against fluoridation that it can get overwhelming.

To simplify things it helps to separate the ethical from the scientific arguments.

For those for whom ethical concerns are paramount, the issue of fluoridation is very simple to resolve. It is simply not ethical; we simply shouldn’t be forcing medication on people without their “informed consent”. The bad news is that ethical arguments are not very influential in Washington, DC unless politicians are very conscious of millions of people watching them. The good news is that the ethical arguments are buttressed by solid common sense arguments and scientific studies which convincingly show that fluoridation is neither “safe and effective” nor necessary. I have summarized the arguments in several categories:

Fluoridation is UNETHICAL because:

1) It violates the individual’s right to informed consent to medication.

2) The municipality cannot control the dose of the patient.

3) The municipality cannot track each individual’s response.

4) It ignores the fact that some people are more vulnerable to fluoride’s toxic effects than others. Some people will suffer while others may benefit.

5) It violates the Nuremberg code for human experimentation.

As stated by the recent recipient of the Nobel Prize for Medicine (2000), Dr. Arvid Carlsson:

“I am quite convinced that water fluoridation, in a not-too-distant future, will be consigned to medical history…Water fluoridation goes against leading principles of pharmacotherapy, which is progressing from a stereotyped medication – of the type 1 tablet 3 times a day – to a much more individualized therapy as regards both dosage and selection of drugs. The addition of drugs to the drinking water means exactly the opposite of an individualized therapy.”

As stated by Dr. Peter Mansfield, a physician from the UK and advisory board member of the recent government review of fluoridation (McDonagh et al 2000):

“No physician in his right senses would prescribe for a person he has never met, whose medical history he does not know, a substance which is intended to create bodily change, with the advice: ‘Take as much as you like, but you will take it for the rest of your life because some children suffer from tooth decay. ‘ It is a preposterous notion.”

Fluoridation is UNNECESSARY because:

1) Children can have perfectly good teeth without being exposed to fluoride.

2) The promoters (CDC, 1999, 2001) admit that the benefits are topical not systemic, so fluoridated toothpaste, which is universally available, is a more rational approach to delivering fluoride to the target organ (teeth) while minimizing exposure to the rest of the body.

3) The vast majority of western Europe has rejected water fluoridation, but has been equally successful as the US, if not more so, in tackling tooth decay.

4) If fluoride was necessary for strong teeth one would expect to find it in breast milk, but the level there is 0.01 ppm , which is 100 times LESS than in fluoridated tap water (IOM, 1997).

5) Children in non-fluoridated communities are already getting the so-called “optimal” doses from other sources (Heller et al, 1997). In fact, many are already being over-exposed to fluoride.

Fluoridation is INEFFECTIVE because:

1) Major dental researchers concede that fluoride’s benefits are topical not systemic (Fejerskov 1981; Carlos 1983; CDC 1999, 2001; Limeback 1999; Locker 1999; Featherstone 2000).

2) Major dental researchers also concede that fluoride is ineffective at preventing pit and fissure tooth decay, which is 85% of the tooth decay experienced by children (JADA 1984; Gray 1987; White 1993; Pinkham 1999).

3) Several studies indicate that dental decay is coming down just as fast, if not faster, in non-fluoridated industrialized countries as fluoridated ones (Diesendorf, 1986; Colquhoun, 1994; World Health Organization, Online).

4) The largest survey conducted in the US showed only a minute difference in tooth decay between children who had lived all their lives in fluoridated compared to non-fluoridated communities. The difference was not clinically significant nor shown to be statistically significant (Brunelle & Carlos, 1990).

5) The worst tooth decay in the United States occurs in the poor neighborhoods of our largest cities, the vast majority of which have been fluoridated for decades.

6) When fluoridation has been halted in communities in Finland, former East Germany, Cuba and Canada, tooth decay did not go up but continued to go down (Maupome et al, 2001; Kunzel and Fischer, 1997, 2000; Kunzel et al, 2000 and Seppa et al, 2000).

Fluoridation is UNSAFE because:

1) It accumulates in our bones and makes them more brittle and prone to fracture. The weight of evidence from animal studies, clinical studies and epidemiological studies on this is overwhelming. Lifetime exposure to fluoride will contribute to higher rates of hip fracture in the elderly.

2) It accumulates in our pineal gland, possibly lowering the production of melatonin a very important regulatory hormone (Luke, 1997, 2001).

3) It damages the enamel (dental fluorosis) of a high percentage of children. Between 30 and 50% of children have dental fluorosis on at least two teeth in optimally fluoridated communities (Heller et al, 1997 and McDonagh et al, 2000).

4) There are serious, but yet unproven, concerns about a connection between fluoridation and osteosarcoma in young men (Cohn, 1992), as well as fluoridation and the current epidemics of both arthritis and hypothyroidism.

5) In animal studies fluoride at 1 ppm in drinking water increases the uptake of aluminum into the brain (Varner et al, 1998).

6) Counties with 3 ppm or more of fluoride in their water have lower fertility rates (Freni, 1994).

7) In human studies the fluoridating agents most commonly used in the US not only increase the uptake of lead into children’s blood (Masters and Coplan, 1999, 2000) but are also associated with an increase in violent behavior.

8 ) The margin of safety between the so-called therapeutic benefit of reducing dental decay and many of these end points is either nonexistent or precariously low.

Fluoridation is INEQUITABLE, because:

1) It will go to all households, and the poor cannot afford to avoid it, if they want to, because they will not be able to purchase bottled water or expensive removal equipment.

2) The poor are more likely to suffer poor nutrition which is known to make children more vulnerable to fluoride’s toxic effects (Massler & Schour 1952; Marier & Rose 1977; ATSDR 1993; Teotia et al, 1998).

3) Very rarely, if ever, do governments offer to pay the costs of those who are unfortunate enough to get dental fluorosis severe enough to require expensive treatment.

Fluoridation is INEFFICIENT and NOT COST-EFFECTIVE because:

1) Only a small fraction of the water fluoridated actually reaches the target. Most of it ends up being used to wash the dishes, to flush the toilet or to water our lawns and gardens.

2) It would be totally cost-prohibitive to use pharmaceutical grade sodium fluoride (the substance which has been tested) as a fluoridating agent for the public water supply. Water fluoridation is artificially cheap because, unknown to most people, the fluoridating agent is an unpurified hazardous waste product from the phosphate fertilizer industry.

3) If it was deemed appropriate to swallow fluoride (even though its major benefits are topical not systemic) a safer and more cost-effective approach would be to provide fluoridated bottle water in supermarkets free of charge. This approach would allow both the quality and the dose to be controlled. Moreover, it would not force it on people who don’t want it.

Fluoridation is UNSCIENTIFICALLY PROMOTED. For example:

1) In 1950, the US Public Health Service enthusiastically endorsed fluoridation before one single trial had been completed.

2) Even though we are getting many more sources of fluoride today than we were in 1945, the so called “optimal concentration” of 1 ppm has remained unchanged.

3) The US Public health Service has never felt obliged to monitor the fluoride levels in our bones even though they have known for years that 50% of the fluoride we swallow each day accumulates there.

4) Officials that promote fluoridation never check to see what the levels of dental fluorosis are in the communities before they fluoridate, even though they know that this level indicates whether children are being overdosed or not.

5) No US agency has yet to respond to Luke’s finding that fluoride accumulates in the human pineal gland, even though her finding was published in 1994 (abstract), 1997 (Ph. D. thesis), 1998 (paper presented at conference of the International Society for Fluoride Research), and 2001 (published in Caries Research).

6) The CDC’s 1999, 2001 reports advocating fluoridation were both six years out of date in the research they cited on health concerns.

Fluoridation is UNDEFENDABLE IN OPEN PUBLIC DEBATE.

The proponents of water fluoridation refuse to defend this practice in open debate because they know that they would lose that debate. A vast majority of the health officials around the US and in other countries who promote water fluoridation do so based upon someone else’s advice and not based upon a first hand familiarity with the scientific literature. This second hand information produces second rate confidence when they are challenged to defend their position. Their position has more to do with faith than it does with reason.

Those who pull the strings of these public health ‘puppets’, do know the issues, and are cynically playing for time and hoping that they can continue to fool people with the recitation of a long list of “authorities” which support fluoridation instead of engaging the key issues. As Brian Martin made clear in his book Scientific Knowledge in Controversy: The Social Dynamics of the Fluoridation Debate (1991), the promotion of fluoridation is based upon the exercise of political power not on rational analysis. The question to answer, therefore, is: “Why is the US Public Health Service choosing to exercise its power in this way?”

Motivations - especially those which have operated over several generations of decision makers – are always difficult to ascertain. However, whether intended or not, fluoridation has served to distract us from several key issues. It has distracted us from:

a) The failure of one of the richest countries in the world to provide decent dental care for poor people.

b) The failure of 80% of American dentists to treat children on Medicaid.

c) The failure of the public health community to fight the huge over consumption of sugary foods by our nation’s children, even to the point of turning a blind eye to the wholesale introduction of soft drink machines into our schools. Their attitude seems to be if fluoride can stop dental decay why bother controlling sugar intake.

d) The failure to adequately address the health and ecological effects of fluoride pollution from large industry. Despite the damage which fluoride pollution has caused, and is still causing, few environmentalists have ever conceived of fluoride as a ‘pollutant.’

e) The failure of the US EPA to develop a Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) for fluoride in water which can be scientifically defended.

f) The fact that more and more organofluorine compounds are being introduced into commerce in the form of plastics, pharmaceuticals and pesticides. Despite the fact that some of these compounds pose just as much a threat to our health and environment as their chlorinated and brominated counterparts (i.e. they are highly persistent and fat soluble and many accumulate in the food chains and our body fat), those organizations and agencies which have acted to limit the wide-scale dissemination of these other halogenated products, seem to have a blind spot for the dangers posed by organofluorine compounds.

So while fluoridation is neither effective nor safe, it continues to provide a convenient cover for many of the interests which stand to profit from the public being misinformed about fluoride.

Unfortunately, because government officials have put so much of their credibility on the line defending fluoridation, it will be very difficult for them to speak honestly and openly about the issue. As with the case of mercury amalgams, it is difficult for institutions such as the American Dental Association to concede health risks because of the liabilities waiting in the wings if they were to do so.

However, difficult as it may be, it is nonetheless essential – in order to protect millions of people from unnecessary harm – that the US Government begin to move away from its anachronistic, and increasingly absurd, status quo on this issue. There are precedents. They were able to do this with hormone replacement therapy.

But getting any honest action out of the US Government on this is going to be difficult. Effecting change is like driving a nail through wood – science can sharpen the nail but we need the weight of public opinion to drive it home. Thus, it is going to require a sustained effort to educate the American people and then recruiting their help to put sustained pressure on our political representatives. At the very least we need a moratorium on fluoridation (which simply means turning off the tap for a few months) until there has been a full Congressional hearing on the key issues with testimony offered by scientists on both sides. With the issue of education we are in better shape than ever before. Most of the key studies are available on the internet and there are videotaped interviews with many of the scientists and protagonists whose work has been so important to a modern re-evaluation of this issue.

With this new information, more and more communities are rejecting new fluoridation proposals at the local level. On the national level, there have been some hopeful developments as well, such as the EPA Headquarters Union coming out against fluoridation and the Sierra Club seeking to have the issue re-examined. However, there is still a huge need for other national groups to get involved in order to make this the national issue it desperately needs to be.

I hope that if there are RFW readers who disagree with me on this, they will rebut these arguments. If they can’t than I hope they will get off the fence and help end one of the silliest policies ever inflicted on the citizens of the US. It is time to end this folly of water fluoridation without further delay. It is not going to be easy. Fluoridation represents a very powerful “belief system” backed up by special interests and by entrenched governmental power and influence.

All references cited can be found at http://www.fluoridealert.org/researchers/fan-bibliography/